Month 1: Scholar’s view

Book Collector: Annuals

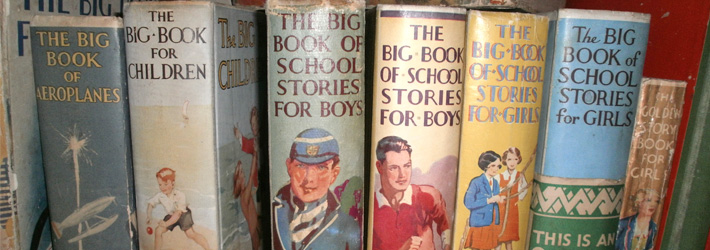

Shelf upon shelf of old children’s annuals is a beautiful sight. Many of the spines are decorated. The titles are intriguing: Little Folks, Chatterbox, Herbert Strang’s Annual. They offer a glimpse into the past: a chance to see what children were reading at the end of the nineteenth century and in the early decades of the twentieth century.

It is striking that many of the shelves contain annuals printed by Oxford University Press. Even OUP’s own archive of its children’s books does not include many of the annuals. And yet they were among the earliest non-educational books specifically for children which the company printed and without them a vital part of the story of OUP’s publishing for children would be lost.

The predecessor to the Oxford University Press Annuals was Herbert Strang’s Annual, published jointly by Henry Frowde of OUP, and Hodder & Stoughton. ‘Herbert Strang’ was in fact the pseudonym of Herbert Ely and Charles James L’Estrange, two editors at Hodder & Stoughton. They were prolific, together writing hundreds of books for boys as ‘Herbert Strang’ and many more for girls using the name ‘Mrs Herbert Strang’. In 1916 OUP bought out the interest and stock for these books from Hodder & Stoughton and took over the sole publication of the annuals. Ely and L’Estrange moved to OUP and continued producing annuals. As well as the yearly compilations of stories and articles they began to produce themed volumes on such subjects as motor cars and aeroplanes.

One reason for annuals being so fascinating today is that because they were expected to be ephemeral they reveal what the publisher anticipated its readership would feel excited about immediately. They were not expected to become classics which were reprinted. In a year’s time, the publisher would bring out the next annual. Consequently an annual might capture passing trends in a way which books, intended to have a longer shelf-life, might not.

Inside an Annual for Boys

Inside an Annual for Boys

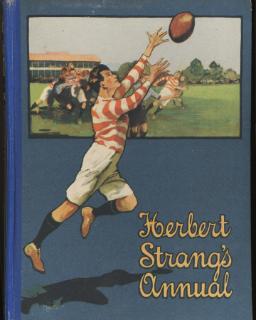

What could a boy unwrapping an annual on Christmas morning in the early decades of the twentieth century hope to find inside his Herbert Strang Annual?

-

He would find anything between 150 and 200 pages, a mixture of stories and articles, many illustrated with black and white line drawings. In addition there would probably be some black and white photographs and a small number of full-page colour plates. Colour plates were ‘tipped in’, a technique whereby the illustration, printed on a higher quality of paper, was mounted between the ordinary pages of the book.

-

Stories reflected the genres of children’s books available at the time, and were often by the same authors. The most popular genres seem to be school stories, adventure stories and historical fiction.

-

School stories were invariably set in (single sex) boarding schools – the norm for the middle classes at the time. They might be light in tone, or even humorous: ‘Page, Petherick & Co: A School Story’ for instance, or ‘The Last Chance: A Public School Comedy’.

-

Adventure stories had titles such as ‘The Diamond Runners’ and ‘My First Wolf’. Settings were often British colonial territories.

-

Historical fiction was often an adventure story set in the past, although there might be period detail to provide an educational element. Herbert Strang himself contributed ‘The Silver Shot: Being an Adventure that befel [sic] Christopher Rudd in the Service of Prince Maurice of Nassau’ and ‘The Phantom Knight: A Story of the Rebellion of 1745’, amongst many others.

-

Articles covered such similar subjects as stories that at times it is hard to tell from the title which to expect. Is ‘Our First Tiger Hunt’ a story or a descriptive article? (a story). What about ‘An Adventure with a Moose’? – this is an article. ‘The Amateur Pirate’ is a story, ‘Sunken Gold: How the Laurentic Treasure was Recovered’ is an article. Other articles covered topics which every boy presumably needed to know about: ‘Laying and Repairing the Submarine Cable’, ‘Eccentric Aircraft’, ‘The Motor Boat’, ‘The History of the Motor Cycle’. Science is covered: for instance in ‘Measuring an Electron’; astronomy, sport, transport, life abroad – usually rugged – and animals, whether hunting them for sport or learning about how they are kept healthy in zoos are all represented. ‘Arithmetical Amusements: A Few Facts and Figures’ by Dr Sphinx’ is genuinely amusing though possibly not for the same reasons as in 1912 when it appeared. My eye was caught by a helpful mnemonic for pi consisting of French quatrains where the number of letters in the words corresponds to the next digit in the sequence.

Forgotten Names

Looking at some of these volumes makes for an intriguing read – was this really what boys were like in the 1910s and 1920s? – and also suggests ideas for the beginning of some research in a neglected area: all these names which are now largely forgotten; so many illustrators for stories which today would be left unillustrated. Names recur and it becomes possible to see patterns: Gunby Hadath keeps cropping up as the author of school stories; quite often the factual articles are written by military men. N Sotheby Pitcher (Lieut RNVR) writes and illustrates articles about ships and the sea. Among the illustrators, two different Brocks are regular contributors. A bit of research provides some more information.

Inside an Annual for Girls

Inside an Annual for Girls

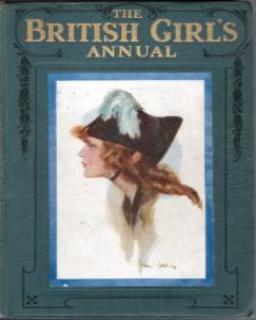

The annuals for girls followed a similar pattern to those for boys: articles, stories, illustrations. Where they differ is in the subject matter.

-

Stories were varied with a sprinkling of poetry. Like the boys, girls were provided mainly with school stories, adventure stories and historical fiction.

-

Historical fiction might be set in stirring times – the rebellion of 1685 was popular as these titles show: ‘King Monmouth: A Story of the Ill-Starred Rebellion of 1685’ and ‘The Silver Ring: Another Story of 1685’ – but the stories were more like romances with a dash of adventure than the ones for boys were.

-

Adventure stories showed girls surviving in dangerous and difficult circumstances, just as those for boys did.

-

Articles suggest that girls were expected to have quite different interests from their brothers. ‘Making Friends With Your Books’, the art of letter writing, and the problems to overcome in editing a school magazine suggest much more decorous pursuits than ‘The Defence of a House’. Again, there is some crossover with the subjects of stories and articles: ‘The Pioneer Girls of the Empire: How the Pluck of the Womenfolk at the Outposts has helped to Build up the Empire’ (an article) has a very similar ring to the story ‘Through the Pluck of a Girl: A Tale of the Yukon’. The ability to survive in difficult circumstances abroad, as a helpmeet to one’s husband, is important.

Forgotten Names

Just like the boys’ annuals, the girls’ volumes contain names which have largely disappeared from common knowledge. There are some exceptions: Angela Brazil is one; Ethel Talbot another. Perhaps this is connected to the resurgence of interest in girls’ school stories which has brought about re-printing of some as part of a nostalgia for the books of readers’ childhoods.