Owning the past, Belonging to the Present

An exhibition review

This temporary exhibition, which was developed by and displayed at Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum (12 December 2020 – 22 August 2021), constituted a thoughtful engagement with two pressing agendas in museum practice: firstly, the role of museums in promoting social inclusion and, secondly, their response to public and media discourse relating to the ownership of cultural property. Cross-cutting both agendas was the extent to which perspectives informed by lived experience can and should play a role in museum presentations of ‘difficult’ or contested histories. These are all subjects of interest to the en/counter/points project, which is researching issues around belonging in different kinds of public spaces, including museums.

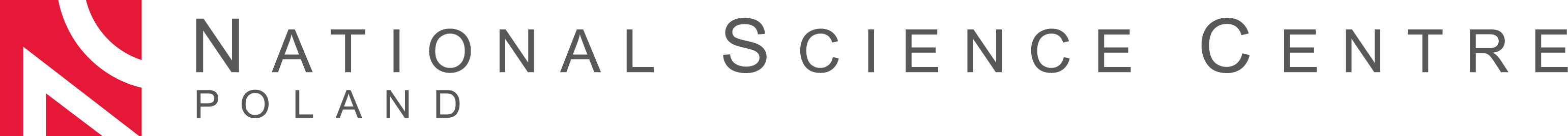

Figure 1

The exhibition was displayed in a lower ground floor gallery, in a long rectangular space (figure 1). Being the Museum’s first dual language exhibition (English and Arabic), text took up a considerable amount of space: seven main text panels were placed sequentially around the room and additional text was printed on large paper scrolls which looped down to the floor from the central ceiling. Objects played a subsidiary role and were limited to three desktop cases and one standing case. The gallery walls were covered with aesthetically-crumpled paper on which had been printed the outlines of a historic map of the Middle East.

As the wallpaper suggested, Owning the Past: From Mesopotamia to Iraq addressed historic processes of mapping and territorial acquisition. In particular, it sought to document “how the borders of the state of Iraq were established following the First World War when British control of the region included a fascination with its ancient past” (‘Owning the Past’ introductory panel). Display elements therefore considered the appropriation of history as a corollary to territorial occupation and explored the role taken by cultural heritage institutions, including the Ashmolean itself, in Britain’s colonial activities in the Middle East. In this respect, the exhibition formed one outcome of a process of critical self-reflection recently begun by the organisation, as at many other collecting institutions across northern Europe. The Museum’s website notes that the organisation “has become increasingly aware of the need to revise the interpretation of its collections and acknowledge our collecting history”, and that it acknowledges its “responsibility to decolonise our thinking, language and practices to reflect a broader range of perspectives and narratives”. Owning the Past thus revealed how museums like the Ashmolean evolved not as part of a disinterested pursuit of knowledge but have always been implicated in global politics and economics. As the third text panel notes, “Britain’s chief concerns in the Middle East were to protect its control of the Suez Canal, access to its empire in India, and vital oilfields of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (later British Petroleum)”.

In documenting the relationship between the colonisation of territory and the colonisation of history, Owning the Past reveals how “Iraq’s ancient past [was] claimed in the ‘West’ as part of its own story” and how European nations thus took “ownership of the physical remains of the region’s past” (text panel 1). Exhibits include a fragment of a c.700BC Assyrian wall relief from Nineveh (Palace of Sennacherib), which the Ashmolean purchased at auction. The exhibition also describes how a major excavation led by the University of Oxford in southern Iraq enabled the removal of thousands of ancient objects to the Museum, as well as considering the direct involvement of museum staff in the colonial mission: former Keeper of the Ashmolean, David Hogarth, for example, was active in naval intelligence during WW1 before becoming Acting Director of the Arab Bureau in Cairo.

As well as addressing the organisation’s complicity in the colonial project, the exhibition also evidenced the Ashmolean’s reorientation towards social agendas. In 2018 it adopted the Ashmolean for All strategy, which aims to improve the way the Museum represents, works with, and includes diverse communities and individuals. In terms of displays, this includes “offering more inclusive narratives around our collections and more opportunities for participation”, as well as developing “collaborative partnerships with under-represented groups to give voice to their experiences and perspectives when re-interpreting our collections through co-created and co-curated displays and interpretation”. The exhibition team included two ‘community ambassadors’, a new role developed by Oxford University Museums, which offers paid work opportunities to individuals with specific community connections and expertise. Individual members of Oxford’s Syrian, Kurdish and Iraqi communities were also invited to contribute to the development of the exhibition’s interpretation. Quotations from them top many of the text panels although we are told that “their thoughts and ideas … also shaped the exhibition including its title” (‘Local voices from the Middle East’ introductory panel). The quotations that have been included sit uneasily against the museum-authored texts, raising important questions about object ownership and the implications of the past for the present which are only partially answered in the exhibition:

I want to hear why all these precious things are here. Did we have a choice that the objects are here?

Personally, going to museums and seeing the way in which Mesopotamia is taught and represented – it is told as a universal history but people are still dying there. The countries we fled to are still responsible.

I want to know what an expert from Iraq or Iran says about a white man coming into their country to draw a border and steal their history. That’s the voice I want to hear.

A final text panel documents various research initiatives headed by or involving Iraqi cultural heritage specialists (The Nahrein Network and EAMENA), however the lingering message is of victimhood and loss:

“The peoples of Iraq have suffered greatly over the last century. Dictatorship, warfare, international sanctions, invasion, occupation – including again by British forces – forced exile and the devastation by the so-called Islamic State or Da’esh have had a terrible impact on people’s lives and communities. In the same period, the heritage that carries people’s identities and histories has been threatened, damaged or destroyed.” (text panel 7)

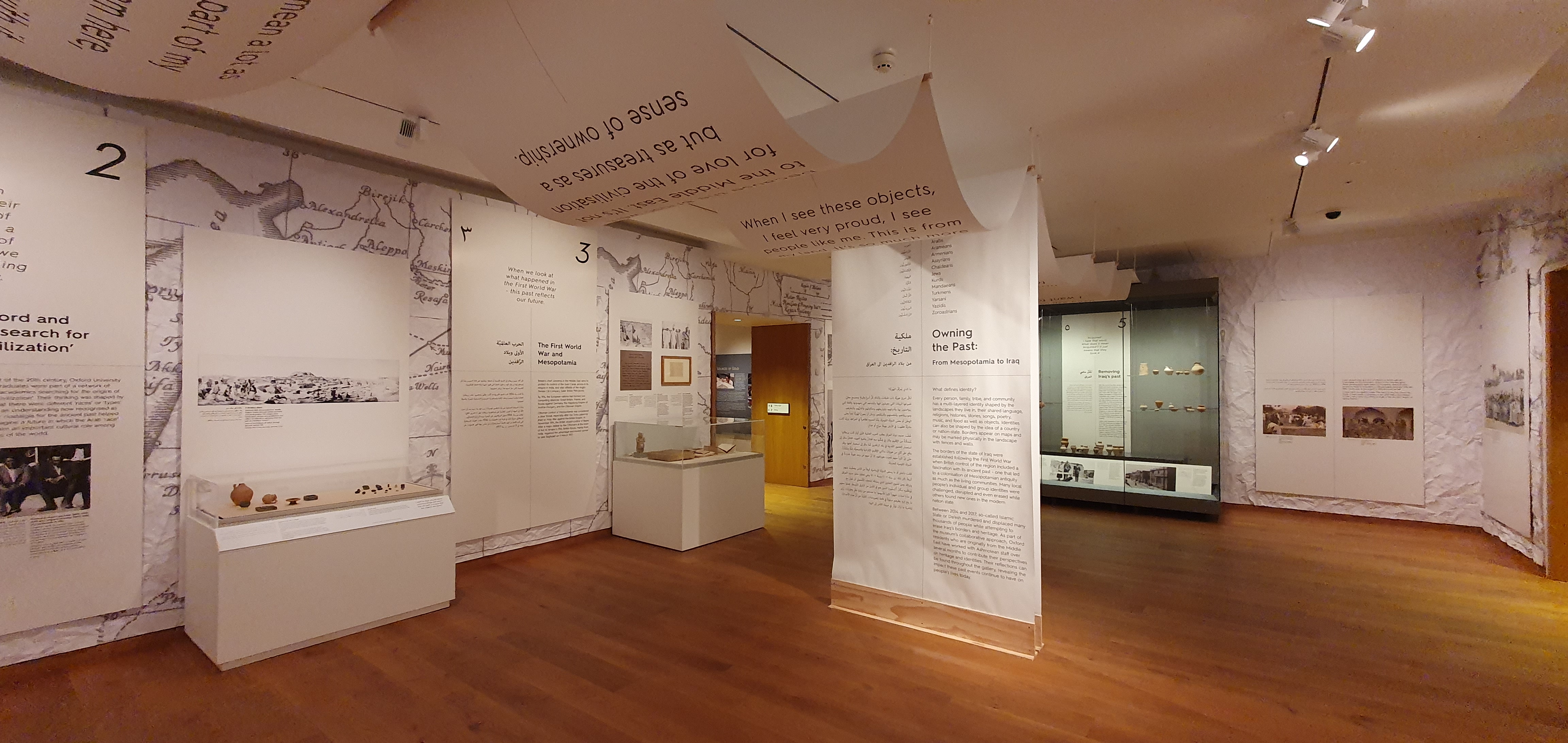

Figure 2

The exhibition is bookended by an installation by contemporary British artist Pier Secunda (figure 2). His large sculpture, which takes the form of broken masonry heaped on the floor, was inspired by Secunda’s 2018 visit to the Mosul Museum where he witnessed the damage caused to collections by members of ISIS/Da’esh. The Ashmolean piece is based on a laser-scanned and 3D-printed copy of an Assyrian relief of a bird-headed spirit from Nimrud, Iraq, which was acquired by the Museum in 1850 and now stands in its reception area. Many of the surviving reliefs at Nimrud were destroyed by ISIS/Da’esh in 2015. As such the installation raises difficult and unanswered questions about the risks to cultural property posed by those who constitute part of its ‘source community’ and might thus have been expected to ensure its preservation.

Overall, the exhibition is to be commended for its attempts to account for the Museum’s own difficult history while incorporating the voices and experiences of those who now form part of its (recently-expanded) constituency. No doubt, museum staff could have gone further in centring the perspectives of Syrian, Kurdish and Iraqi people and in mitigating the overall sense of loss and displacement by considering how the Museum’s historic collections can connect to contemporary practices of identity-making and belonging amongst the city’s residents. In a display dominated by text, and to a lesser extent objects, images of people, included the quoted individuals, would also have helped underscore the agency and resilience of those who, in this exhibition, tended to remain the objects rather than the subjects of the display. Nevertheless, regardless of these limitations, Owning the Past makes an important contribution to evolving models of museum practice.