Month 1: Poet’s view

The Filing Cabinet

During our first meeting with Brian Alderson, he mentioned a Companion to Children’s Literature, the material for which he had painstakingly gathered several years previously, but which has never been published. “It’s all in a filing cabinet,” he said. “Can we see it?” I asked. “Yes of course,” said Brian. “It’s just there.” And sure enough, there it was – a large, brown, unexceptional piece of office furniture, standing in the shadows at the back of the room. It seemed to me, even on that initial encounter with Brian Alderson and his archive, that this image epitomised his whole collection: extraordinary things hidden in the most surprising of places.

The Warehouse

The first sight of Brian Alderson’s main collection of books was overwhelming. It looked nothing like a library or a special collection: it looked like a huge, bright, crammed collection of books. Aesthetically, it was very pleasing – and rare: it’s not often you get to see a private collection of this scale. The visual appearance seemed intrinsic to its magic, somehow. It would be nice if it could be preserved, if the archive ever moves. Why? Because it reflects the impetus behind the collection: to explore for pleasure and knowledge; to discover the relationships between things.

The Never-Seen Eliot

To my surprise, Brian Alderson stated on our first meeting that he started by collecting poetry; T.S. Eliot in particular. “I would like to see that first T.S. Eliot book that you bought,” I said. “Yes, I’ll get it for you,” said Brian. I think he said it was the ‘Ariel’ Poems. But we moved on to other topics, and the Eliot was forgotten. I asked again the following week, and then again towards the end of our project, but I still haven’t seen it.

A Hidden Poet

During our second visit to Brian Alderson’s archive, he told us a story about a visit he made to an auction in Middleham (now the auction house Tennants, in Leyburn). On this particular occasion, he bought a box of pamphlets about Yorkshire dialects, costing ten pounds. His wife Valerie was cross with him for buying this, as she knew they would never sell in the little bookshop they owned. While looking through the pamphlets at home later, Brian came across a little volume of poems written by ‘Hinks’, a solicitor in Darlington. This Hinks had been friends with the station master at Darlington station, who had sent the pamphlet off for reviewing. Tucked inside the volume Brian found a letter from one of the reviewers which began: “Thanks for sending me this.” The letter was signed “George Orwell.”

Among Poets

For his first job, Brian Alderson worked in a bookshop-wholesaler’s. The other graduates working with him included David Wade (who became radio correspondent for the Times), Chris Downs (who became a Dresser at the Old Vic) and Jon Silkin, who became a poet and editor of Stand.) How strange it is the way these things happen: the other archive that I am researching for Newcastle University is the Bloodaxe Archive. Neil Astley who runs Bloodaxe books, spent his student years working on Stand for Silkin, just before setting up his own publishing house.

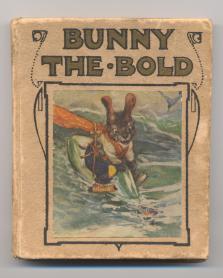

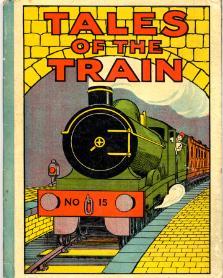

Titles

All through this project I was aware of the wonderful titles I was hearing and seeing – both of the children’s books in Brian Alderson’s collection and of his own articles and talks. “Enid Blyton and the Big Red Ledger,” “How Are We Doing, Miss Butler?” and “The Irrelevance of Children to Children’s Book Reviewers” are just three examples. I scanned whatever children’s book covers I could get my hands on, often just because I liked their titles so much.

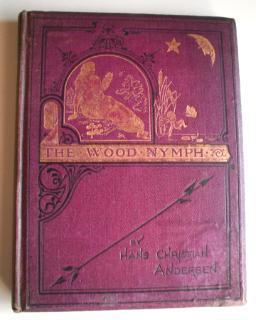

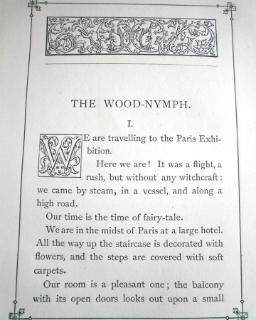

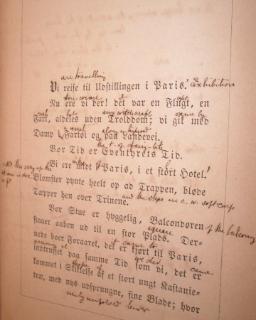

We are travelling to the Paris Exhibition

Using this single opening line of Hans Christian Andersen’s story, Brian took us through several versions of the same tale. Of particular interest was a translator’s ‘working copy’, which had the translator’s notes written in between the Danish lines. This would be an invaluable text for anyone interested in the process of translating, and the changes and choices that are being made during the conversion.

Ask the Old Girl

While showing us his various versions of Hans Christian Andersen tales, Brian Alderson pointed out an omission: a poem by Andersen which doesn’t seem to have ever been translated into English – until now. Brian read us his version, set in Covent Garden and which begins, “Now once there was an old carrot/Who'd reached the hard and knobbly stage/But boldly set out to get married/To somebody half his age […]”

Relationships

When writing his article about the illustrations of Maurice Sendak, Brian Alderson found that there were copyright problems regarding the reproduction of Sendak’s images. One way around this was to write about the illustrators that influenced Sendak. This gave rise to a different, but revealing study, which demonstrated the relationships between illustrators. Identifying these sorts of correspondences is something which is central to Alderson’s activity as a collector. From an outsider’s point of view, it also demonstrated the scope of Alderson’s collection.

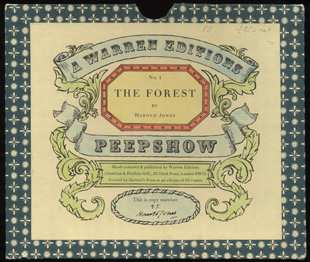

Slipcase

Slipcase

As a poet, I am attracted to books which contain other books, tiny books, books which open into something else, or books which move or change. They capture one of the aims of a poet, which is to create a small box of words which can be turned or folded out in the reader’s mind to make a different – or alternative – picture.

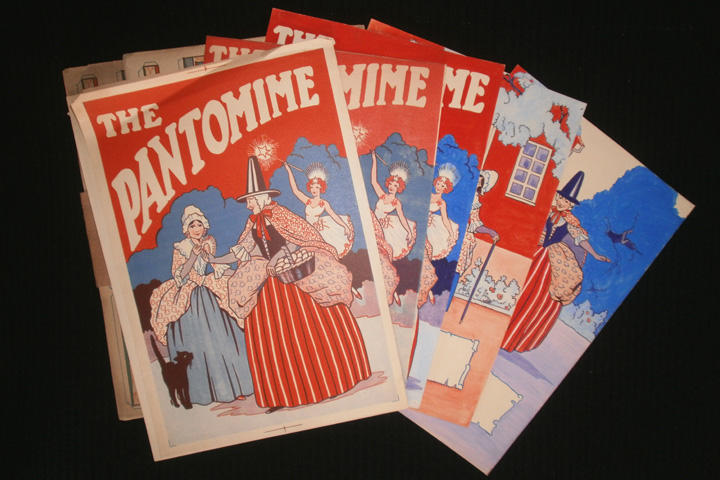

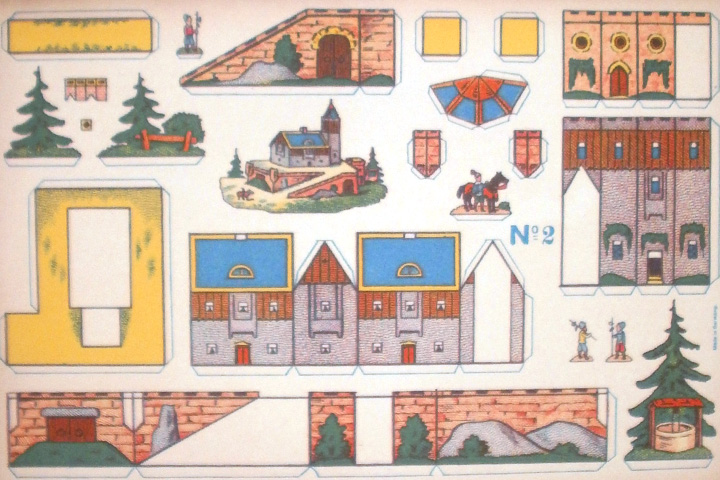

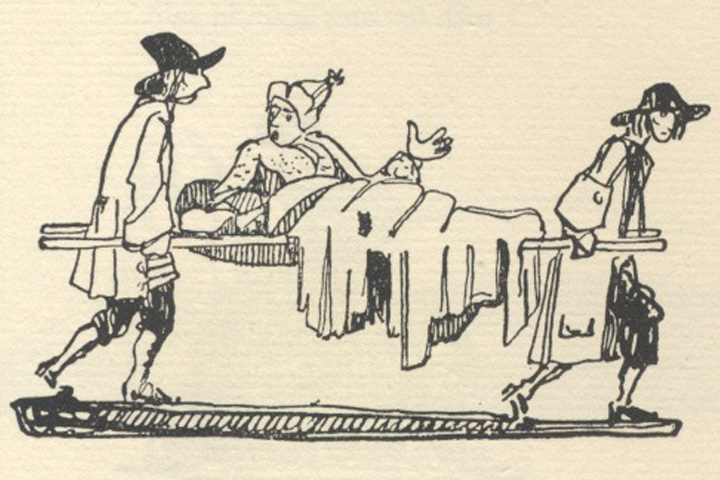

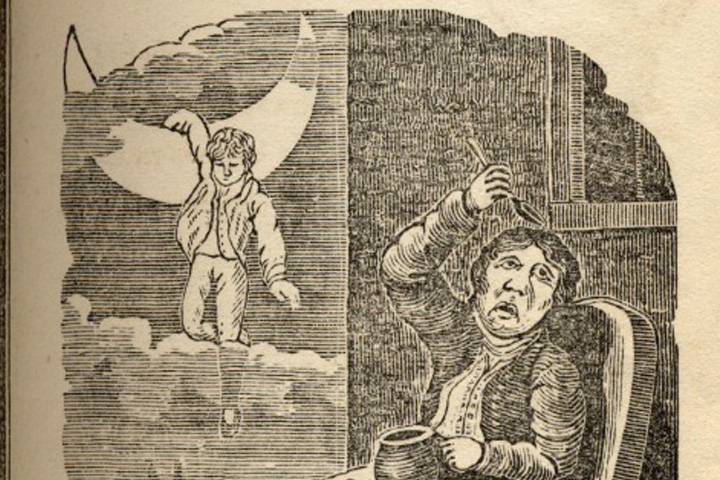

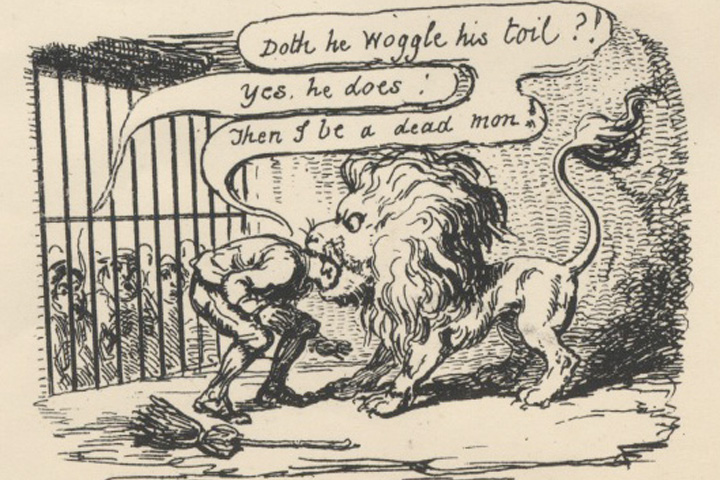

Paper Pantomimes

One day, Brian Alderson produced three large cardboard boxes, which he bought, years ago, at a sale in Sotheby’s. “Who would like to go through these?” he asked. I immediately volunteered: inside were some very striking things, which I had never seen before: large, flat ‘model sheets’, brightly coloured and depicting a range of scenes, from pantomimes to motor boats. I have tried to find out more online about what these are exactly, but nothing’s come to light yet.