Research Blog

Welcome to the MEMS research blog

We wanted to give researchers (staff, ECRs and PGRs) from universities and colleagues from local libraries, archives and cultural institutions a forum where they can give informal updates on their current research. We'll be asking one person per month to contribute an update but all contributions are welcome so if you would like to add a blog post, please email Ruth Connolly or the MEMS administrator Peter Hebden with your post (and a nice picture if you have one).

Objects, Extensions, Prosthetics: Symposium Report (Emily Rowe, English Literature)

How do objects act as extensions of the premodern self? As literal or figurative prosthetics? These were just some of the questions set at the outset of the Newcastle University MEMS symposium held on 16th May 2018. The papers of the day, given by a range of PhD students and early career researchers, along with a keynote from Professor Helen Smith (University of York) and a round-table discussion, all generated themes asking how we can expand the field of premodern object studies in the face of the recent surge in materiality studies.

After discussing some of these themes in my own work on language materiality and words-as-objects, the first panel of the day was closed by Kimberley Foy (Durham University). Foy’s discussion of early modern European elites and their trends of lace and cutwork immediately elevated discussion, and offered detailed insight into the multiple meanings of this costly material. Foy’s focus on visual depictions of elites, including the portraiture of William Larkin (1585-1619), and their tendency to sneak lacework into every portrait, even if it needed to peak out of armour or be ruffled on shoes, highlighted the importance of this fashion item in elite culture and the ways it functioned as a shared language between European courts. Lace could be both symbolic of status, but also an important aspect of material culture for establishing friendships as it was granted as gifts and had an ‘international audience’.

The second panel of the day focused on devotional objects, and produced a range of papers and ideas that considered the variety of objects that could be linked to premodern notions of devotional identity. Catherine Evans (University of Sheffield) opened the panel with her paper on devotional ‘graffiti’, on surfaces including wood, walls, and glass windows. Her fantastic analysis of these surfaces intersected with a close reading of George Herbert’s ‘Love-joy’ (1633) and John Donne’s ‘A Valediction of my name, in the Window’ (1599?). Evans showed us early modern ‘writing rings’, designed to inscribe phrases on walls or windows, arguing that inscription had the ability to grant ‘magical powers’ to surfaces they were written on.

Next in this panel was a paper exploring embodiment and textual meaning in Grace Cary’s 1644 prophetic manuscript from Claire McGann (Lancaster University). McGann highlighted the meaningfulness and importance of the material form of Cary’s manuscript, which in accordance to a message from God she hand-wrote her prophecies, tailoring the medium to her message. It was clear from McGann’s paper that the potential for a physical and emotional connection with the writer of this manuscript was elevated through its material form and its role as an embodied representation of Cary - both her body and her prophecy.

Dr Elizabeth Biggs (University of York) closed this panel, and her study of the collections at Durham Priory and their relation to monk and Catholic identity-fashioning combined perfectly with the earlier themes of the panel on text, writing, and devotional self. Biggs’ analysis of just one of the books found at this priory library illuminated the ways monastic communities self-fashioned themselves in the sixteenth-century, and how these books went on to become sites of memorial heritage, even ‘talismans’ for Recusant families eager to retain some material emblem of a now distant Catholic past. The opportunity for identity to be engraved onto devotional objects in both literal and metaphorical ways was present throughout this panel, along with the potential for such objects to be instilled with near-magical properties through their active relationship with faith, the inner self, and memory.

The final panel of the day centred on ‘bodies as objects’, and the sickly and gory moments of embodiment and dismemberment in premodern literature. Jenny Hunter (Northumbria University) opened the panel with some fresh insight into seventeenth-century plague literature, which, so often mimicking classical epics to form their own sort of ‘plague epics’, highlighted premodern conceptions of the body, morality, and worldly hierarchy in relation to the plague. Hunter examined Thomas Clark’s Meditations in my Confinement (1666), in which Clark quarantines himself during the plague outbreak of the time and finds his material relationship with his infected body and the confines of his home heightened. Hunter notes the early modern belief that the plague could be a ‘physical manifestation of sin’ and the individual moral obligation to isolate if infected.

This panel was closed with a paper from Mary Odbert (The Shakespeare Institute, University of Birmingham) who explored the formation of corporeal selfhood in Titus Andronicus and Coriolanus. Both plays offer scenes of bodily disfigurement and dismemberment, and rather like the devotional manuscripts and surfaces discussed earlier in the day, Odbert argues that the body becomes a ‘locus for the inscription of meaning’, with bodily parts such as Titus’ hand becoming physical extensions of inner emotion. Odbert’s paper also highlighted the ways in which the body ‘makes’ the self, scars and wounds are similar loci of meaning and ‘make’ Coriolanus, highlighted the interrelated constitutive powers of the body as an object and the self, and the lack of a clear boundary between the two.

The day closed with a keynote from Prof. Helen Smith followed by a small round-table discussion of the day’s themes and papers. Smith’s paper, ‘Of Men and Metals’ intersected with many of the afternoon’s themes including embodiment and the complex, constitutive relationship between object and subject, matter, body and self. Smith highlighted the metonymic relationship between metals and the composition of man in early modern literature, particularly through uses of mettle/metal puns that saw a literal connection between the substance of a man and the substance of various metals and elements. Here we saw textual moments where human bodies and souls could be ‘worked upon’, ‘refined’, and like metals, a topic that saw a rise in the scientific literature of the period, could be ‘corrupted’, ‘purified’ and ‘transmuted’.

Attendees and speakers trickled in and out over the course of the afternoon, so by the day’s close we had an intimate round-table discussion aided by nibbles and wine. Topics including rhetoric, and its ability to function in material embodied ways, and the memorial materiality of both language and objects were raised. We highlighted how despite a lack of gender-focused papers offered, questions and discussion often found its way back to gender and how the current ‘material turn’ in premodern scholarship can approach gender in a way that doesn’t simply link domestic or shopping culture to women, but still celebrates the potential for object studies to cast a light on marginalised experiences and recover their voices.

Topics of gender, embodiment, and the materiality of texts and word were present throughout the day, and emphasised the many ways scholars are now rethinking our relationship with literary and historical objects, attempting to offer more than the straightforward ‘object-study’ and engage with the wider contexts of the premodern period that might typically be seen as immaterial or even transient. The day offered a chance for scholars ranging from PhD to established academics to discuss work and get a glimpse where this burgeoning field might take us next. (Emily Rowe @emi_rowe)

Manuscript prints (Aditi Nafde, English Literature)

What happens when a new form of technology is invented? Do we reject the older form or cling on to it as something familiar? I have been thinking about these questions in relation to medieval books as part of my new project, From Print to Manuscript. In particular, I have been looking at the way in which print, first introduced by Caxton in England around 1476, affected the production of manuscripts. We’ve moved beyond the early notion that ‘print culture’ displaced ‘scribal culture’ soon after its invention (Elizabeth Eisenstein). But how exactly did scribes – whose livelihood relied on producing manuscripts – and readers – who were familiar with the reading practices requested by manuscripts – respond to this technological change? Did print change the way in which scribes produced manuscripts? And, most fundamentally, did print change the way in which readers read books?

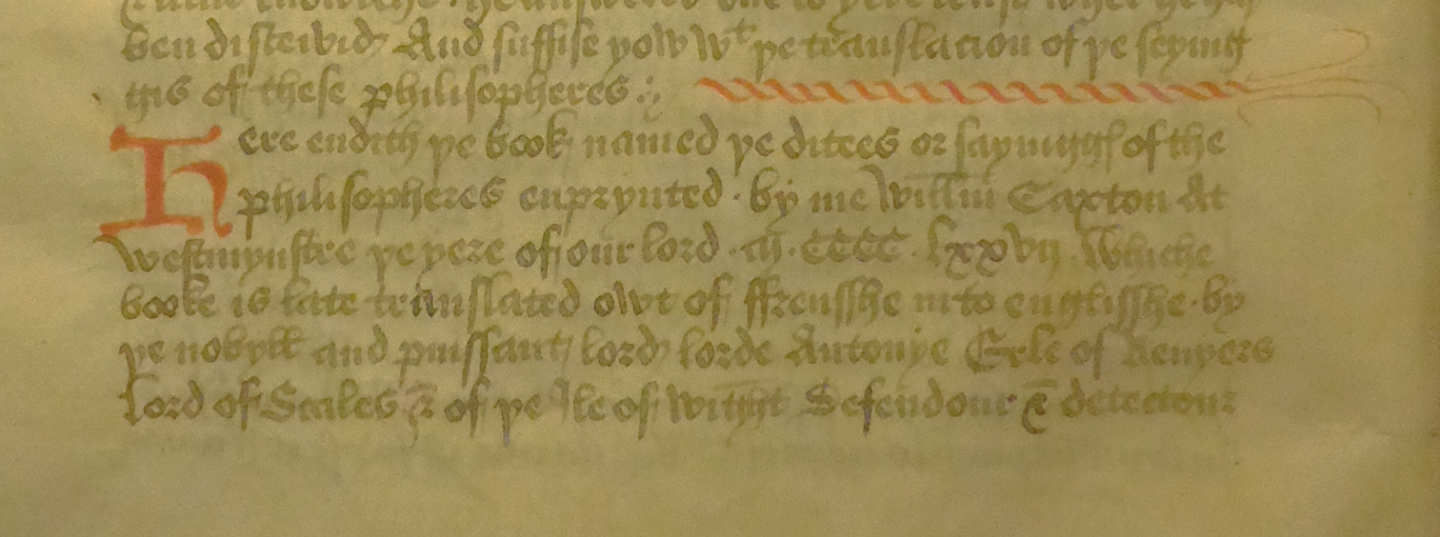

My starting point has been curious books such as British Library Additional 22718, a manuscript copied from a Caxton print. The manuscript ends in a colophon which reads:

[Here ends the book named the Dicts or Sayings of the Philosophers, printed (enprynted) by me, William Caxton, at Westminster, the year of our lord 1477]

BL Additional 22718 colophon

The manuscript is clearly not ‘enprynted’. Yet, in copying out the colophon from the printed book, word for word, the scribe suggests that he has a reverence for the print. It also suggests a rather flexible attitude to the book, one which perhaps didn’t clearly distinguish the handwritten manuscript from the printed book. The term ‘enprynted’ itself might have been used rather flexibly to mean any form of text copying, not just print. Its use certainly suggests a more subtle delineation between print and manuscript than our use of those terms now.

Two further books show more extensively the impact of print on the production of manuscripts.

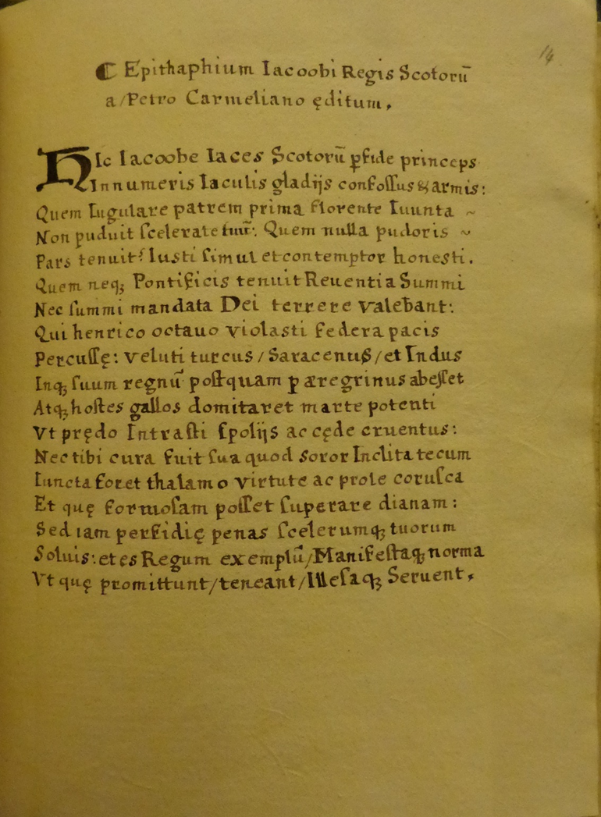

British Library Additional 29506, above, is a transcript of a tract which was printed by Richard Pynson. British Library Additional 36985, below, an account of the founders and benefactors of Tewkesbury Abbey. Both are made to look like printed books. There are line drawings and large initials which imitate very closely the patterns and styles used in producing woodcuts.

These two books are later examples of manuscripts that look like print, produced at a time when print was more established. There are much earlier examples, produced when print culture was only just beginning to flourish in the last quarter of the fifteenth century. A fruitful place for investigation is the number of manuscripts which have been identified as being copied from printed texts, which is where my project starts.

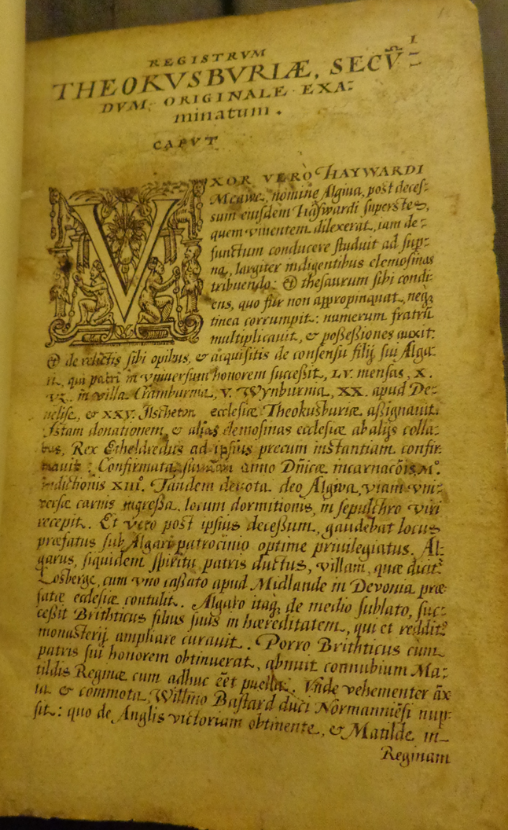

St John’s College Oxford, MS 266 is the most famous example of the impact of print on manuscript production. The book is also known as STC 5094, STC 5083, Cx2, b.2.21 because it is in part manuscript and in part print: it is a composite or hybrid book. It combines Caxton’s print editions of Troilus and Criseyde, the Canterbury Tales, and Quattor Sermones with a manuscript copy of Lydgate’s Siege of Thebes. It was fairly common for disparate fragments to be bound together without regard for their material form. The compiler did not think the difference between manuscript and print enough reason to dismiss the combination of the two. But the complex interaction of the two forms within this book suggests that the combination of manuscript and print goes beyond mere dismissal of material form.The book has, for instance, been ruled throughout in red ink. Both sections of the book are ruled, that is, both the manuscript and the printed portions. The ruling in the manuscript portion is an expected, functional guide for the scribe; the ruling in the print section, however, is purely decorative. It has no particular function in the printed portion and it clearly been added later, as indicated by the smudges in black ink that run along the ruled line where the lines have been drawn over the print.

More interestingly for my project, however, is that the manuscript portion is made to look like the printed portion. Specific features of a print page are carried over into the manuscript section of the book, features that usually come from practical or technological changes in producing printed books that are usually not part of the process of manuscript production. The running titles are consistent throughout the entire manuscript portion of St John’s 266: they are not abbreviated or truncated in any way which was rather uncommon in literary manuscripts from both before and during this period of manuscript production. Instead, they are repeated in their unabbreviated entirety on each page. The running titles in the printed portions of the book are executed identically simply because it was easier for a printer not to reset them with each change of forme. The manuscript portion continues this layout, though it is unusual (not to mention tedious and laborious) for the scribe to do so. The text space is almost identical throughout the entire book and it’s unlikely that this is coincidental. This suggests that the print and manuscript sections of this book were not just bound together, but were compiled in such a way as to integrate them, making them look like a single endeavour. The manuscript was made to look like a printed book – specifically, the printed book with which it was bound – and perhaps even commissioned to be added onto the print.

St John’s 266, with its unusual layout for Siege of Thebes manuscripts was used by Wynkyn de Worde to create his print edition of the Siege of Thebes. There are printers’ marks throughout the book in margins which correspond to the first lines of the text in printed edition (STC 17031, c.1497). This means that Wynkyn de Worde’s printed copy of Siege of Thebes was based on the manuscript copy in St John’s 266 which was made to look like a printed book. The movement from print to manuscript and back to print here illustrates rather nicely the messy processes and flexible attitudes towards printed books and manuscripts produced after the emergence of print.

The manuscript, then, might be said to be ‘finishing’ the printed text: printed books were often produced without decoration which was finished by hand. But equally, St John’s 266 shows that manuscripts also seem ‘incomplete’ or ‘unfinished’ without some features of print. Manuscripts such as St John’s 266 make both print and manuscript forms seem rather ‘transitional’.

Having now examined a number of such hybrid books, it’s become clear just how often missing pages of printed texts were completed by hand and how often the manuscript completion aimed to imitate the style of a printed book.

The Huntington Library RB 104537

Not only did scribes ‘finish’ the printed book by importing manuscript features into them, they altered their manuscript features in line with print practices. Scribes were building a wider repertoire of features that were an amalgam of print and manuscript features. But this could have even been the job of the reader, who desired a complete copy of a text for his collection, and who had purchased an ‘unfinished’ print copy of a book. Might this suggest, then, a new type of reading: one in which the reader interacts with the book to ‘finish’ it while reading? This is the question that I’ll be thinking about next.

Old English into Old Norse

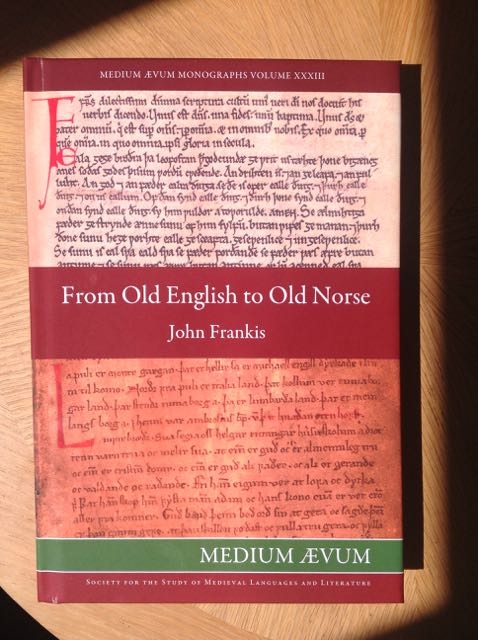

A number of medieval manuscripts contain texts in Old Norse-Icelandic that seem to be based on, and may in varying degrees be translated from, originals written in Old English. This study aims to consider these to see what can be deduced about their origins and history.

Surviving records of Germanic languages before 1200 include many texts translated from Latin, but translation from one vernacular into another is rare (the Old English Genesis B, translated from Old Saxon, is the best known example), and these ON translations from OE, almost certainly from the 12th century, therefore have an interesting place in the records of early Germanic languages. They include one substantial ON text, a translation of Ælfric’s homily De falsis diis, and also partial translations of Ælfric’s De auguriis and the anonymous Prose Phoenix.

It has hitherto been assumed that De falsis diis was translated in Iceland because the manuscript containing it was preserved, and possibly compiled, in Iceland, but this assumption is hard to justify in the light of what is known about the circulation of Old English (and especially Ælfric) manuscripts.

Establishing the place and date of translation is problematic and there is no decisive evidence. Relevant evidence discussed here includes access to, comprehension of and esteem for the OE texts concerned (suggesting a date before 1200) and the development of the use of the Latin alphabet for writing Scandinavian languages (suggesting a date after 1100).

All the relevant texts are considered and all contain material of intrinsic interest; the OE and ON versions of De falsis diis are printed in parallel to facilitate comparison.

For more, see John Frankis, From Old English to Old Norse, a study of Old English texts translated into Old Norse with an edition of the English and Norse versions of Ælfric’s De falsis diis. Medium Ævum Monographs 33 (Oxford: Society for the Study of Medieval Languages and Literature, 2016).

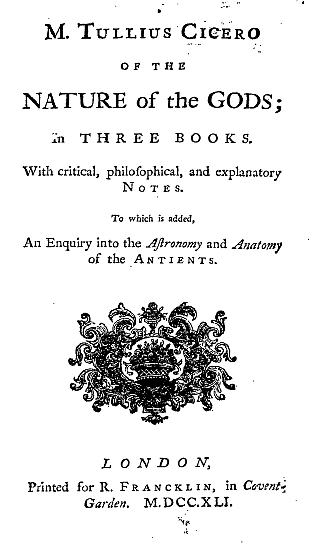

Free Thinking and the afterlives of the Ancients (Katie East (Classics))

The intellectual discourse galvanising the progress of the Enlightenment in England was rife with disputes centred on the question of belief: on what merited belief; on what the basis of belief should be; on whether belief should be rooted in reason, nature, and science, or tradition, authority, and faith. In the midst of these debates, which would be central to the achievement of what may be termed ‘modernity’, it is surprising to discover that the scepticism represented and transmitted in the works of Cicero should receive attention. This seems to directly contradict the commonly held assumption that the rejection of tradition in much of this discourse necessitated the rejection of the traditional authority of the ancients.

Yet Ciceronian Scepticism is not only present in these exchanges, but became the subject of something of a tug-of-war, between those orthodox writers arguing for a providential God and consequently the existence of facets of Christianity beyond human understanding, and those heterodox writers who rejected entirely the notion that any aspect of true religion could exist beyond the comprehension of reason. Two Ciceronian texts were at the centre of this argument: the theological dialogues De Natura Deorum and De Divinatione. In particular, the representation within these dialogues of the relative positions of the Stoics and the Academic Sceptics regarding natural philosophy: their differing understandings of God, the universe, religious practice, and the forces underpinning religious belief. Early modern writers from differing intellectual positions found something in these texts to support their ideas, a diversity perhaps best illustrated by the exchange which took place in 1713 between the radical Freethinker Anthony Collins and the scholar, clergyman, and defender of the establishment Richard Bentley.

Anthony Collins, attempting to co-opt Cicero into his gallery of great Freethinkers, wrote of De Natura Deorum that Cicero had ‘endeavour’d to show the Weakness of all the Arguments of the Stoicks (who were the great Theists of Antiquity) for the Being of the Gods’, and of De Divinatione that Cicero ‘destroy’d the whole Reveal’d Religion of the Greeks and Romans, and show’d the Imposture of all their Miracles, and Weakness of the Reasons on which it was pretended to be founded’.

The assumption underwriting Collins’ reading of these texts – that the position of Cicero himself must be identified with that of the Academic Sceptic in these texts – is enthusiastically rejected by Richard Bentley, who directs the reader’s attention to the judgement at the end of De Natura Deorum, where Cicero – under his own name – claims to endorse the Stoic understanding of the divine. Bentley writes, ‘and what now becomes of our Writer’s True method and Rule? Whatsoever is spoken under the Person of an Academic, is that to be taken for Cicero’s Sentiment? Why, Cicero declares here, that he sided with the Stoic against the Academic: and whom are we to believe, Himself or our silly Writer?’

It is the essence of this dispute – its reasons, and its presence in the discourse from the writings of Herbert of Cherbury to those of David Hume – which constitutes the core of my research as a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow here at Newcastle University. I look forward to profiting from the University’s lively research interest in the early modern period, so that I can create a narrative of the fate of just one intellectual tradition – Ciceronian Scepticism – in amidst the myriad ideas which interacted to bring about the Enlightenment.

Hadrian's Wall: Centring the Periphery (Rob Collins, Archaeology)

Hadrian's Wall is widely known as a romantic, windswept monument whose ruins attest to the edge of the lost Roman Empire. But despite centuries - yes, centuries - of research, many unanswered questions remain. My research has focused on using Hadrian's Wall as a means to understanding border and frontier societies and the hybridity of cultures across time and space. Hadrian's Wall and the End of Empire (2012, Routledge) examined the archaeology and history of the Wall in the 4th and 5th centuries AD, exploring how the northern frontier zone could not simply be seen to 'collapse' in the face of Britain’s separation from the Roman Empire in the early 5th century, and my research has suggested that the emergence of the kingdom of Northumbria as an 'English' powerhouse in the early Middle Ages may be a result of its Roman frontier origins rather than any incipient Anglo-Saxon contribution. The remains of the Roman Empire stood for centuries, and new technology allows us to explore it in stunning detail, as with the laser scans completed as part of the Frontiers of the Roman Empire Digital Humanities Initiative (such as this tombstone from South Shields of the freed slave Regina, who originated from Essex or Hertfordshire, and who married her former master Barates of Palmyra).

More recent research has used the Wall as a vehicle for understanding the roles of borders and frontiers, and how these ideas are disseminated across diverse media in antiquity as well as with contemporary audiences. On-going research entitled The Phallus and the Frontier catalogues the occurrence, morphology, chronology, and provenance of phallic carvings in the Wall corridor. Significantly, this research indicates a more sophisticated use of the apotropaic belief in phallic symbolism than has been previously recognised. For example, the Birdoswald sector has been suggested to be a 'problem' or 'priority' area for the Roman army, and the use of phallic carvings suggested that the Romans also invested in the creation of a magical barrier or force field to reinforce the physical barrier of the Wall.

Another strand of research (collaborating with Stacy Gillis, SELLL), Reading the Wall, is exploring the way in which the Wall permeates diverse media as a cultural force. This is seen widely in fantasy literature, such as George R.R. Martin's Game of Thrones, where his gigantic Wall of ice was inspired by a visit to Hadrian's Wall in 1981. Authors Garth Nix (the Old Kingdom series) and Christian Cameron (the Traitorson Cycle) have recently spoken at Newcastle University on the influence of Hadrian's Wall in the creation of their own iconic Walls in pseudo-medieval fantasy.

Garth Nix, Rob Collins and Christian Cameron at Hadrian's Wall

Defining the Global Middle Ages - Scott Ashley (History)

For the past three years I have been a co-ordinator of an AHRC project called ‘Defining the Global Middle Ages’, along with colleagues in Oxford and Birmingham. We gathered together a shifting group of about twenty historians and archaeologists of predominantly Afro-Eurasia (we have had one or two scholars of the ancient Americas, but they are thin on the ground in Europe!) in a series of workshops looking at issues such as periodization, historiography, networks (the theme of the Newcastle workshop in September 2013) and cultures of recording. The discussions have always been experimental and conducted in the spirit of open enquiry rather than specialist rank-pulling. As a historian of the European early middle ages my knowledge of T’ang dynasty China or the east African trading-towns of Zanzibar were, well, pretty close to nil. But thanks to generous give-and-take conversations we all feel that we have a stronger sense of the sometimes unexpected connections between different parts of the world pre-1500 and how comparisons might be made between those diverse societies, the building blocks of new and exciting large-scale stories.

Newcastle University has a very strong track record of teaching and researching World and Global History, thanks to the pioneering work of R.I. (Bob) Moore, Professor of Medieval History here from 1993 to 2004. After introducing the teaching of World History onto the syllabus during his time at Sheffield, Bob imported the concept on his move to the north-east. As the designer and module leader of the current incarnation, ‘World Empires’, I am currently entrusted with keeping the flame alight. It was good to look around the final workshop held last month (March 2015) in Oxford and count the number of scholars around the table who were or who had been attached to Newcastle in some shape or form, either as staff, researchers or students.

This last day-long workshop was our attempt at public engagement and we had invited a number of postgraduates, museum curators and school teachers to University College to try and get them interested in what we had been doing since 2012. Despite an early start (9am on a Saturday), once the caffeine kicked in the day was a great success. I gave a short talk on networks in world history, using some examples and concepts from the Viking world that I have been wrestling with for a few years now. But rather than it being a day of talks by ‘experts’, a daunting prospect for anyone, an energy was quickly generated in the room by an open-minded group willing to learn from each. I certainly left feeling as if we were on the right track. It was also nice that a set of maps showing long-distance connections I had made for my Newcastle ‘World Empires’ lectures had been used by one of the school teachers. The flame still burns …

To find out more about the project:

http://globalmedieval.modhist.ox.ac.uk/

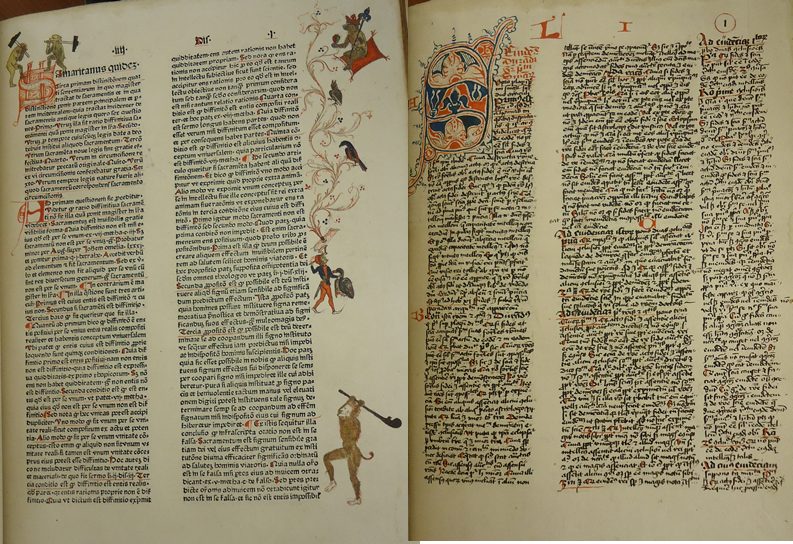

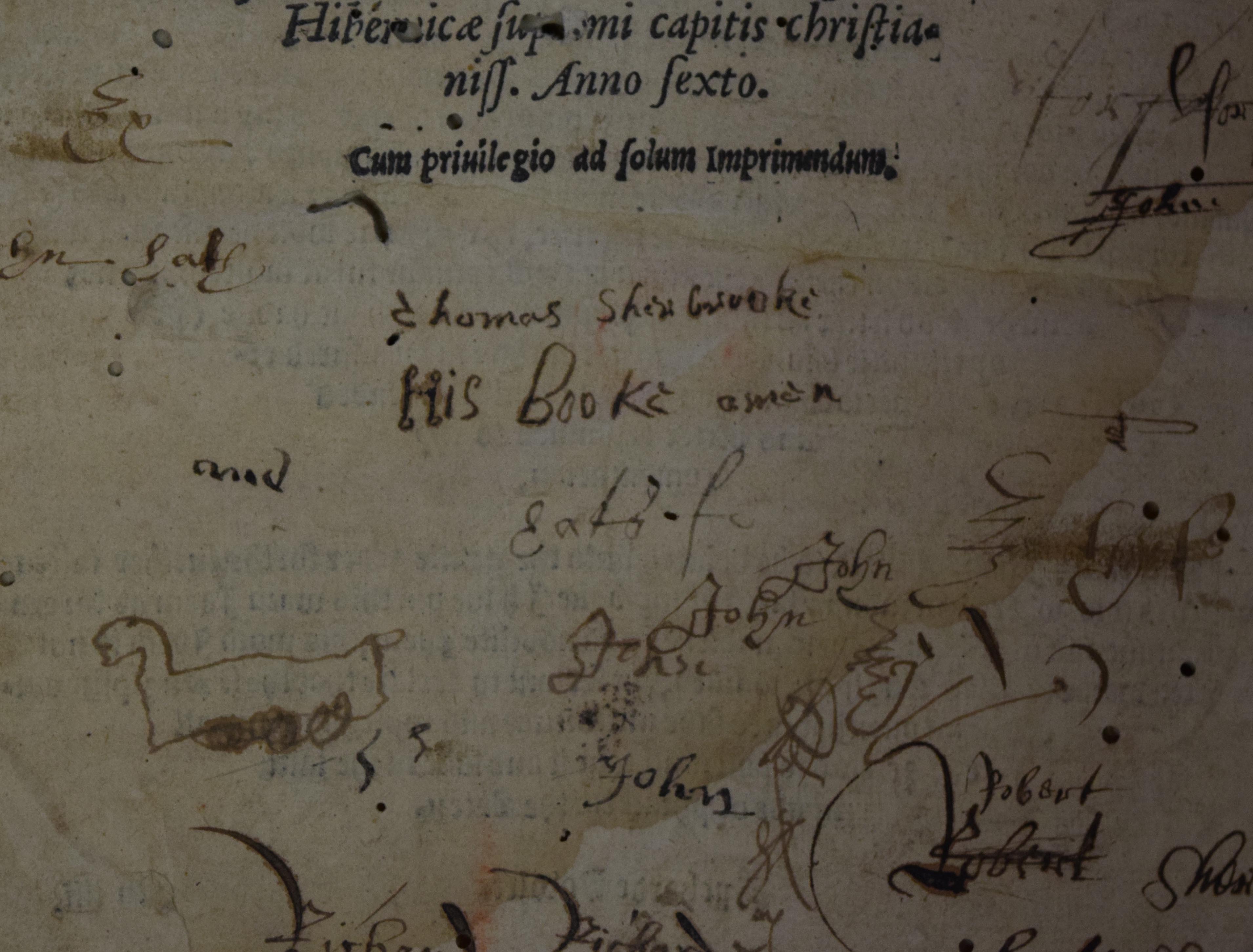

Early Modern Children’s Dictionaries at the Folger Shakespeare Library - Harriet Archer (English)

Modern readers are usually discouraged from scribbling in the margins of their books, but the wealth of graffiti left in printed Renaissance texts is one of our key resources for understanding how and why particular books were read in the early modern period. Every turn of the page can add a new dimension to a reader’s profile; notes, underlining and even doodles help to build up a picture of the book’s provenance and uses, layer by layer. I currently hold a short-term library fellowship at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, DC, where I have been delving into the fascinating and sometimes surreal world of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century manuscript marginalia.

A rich seam of marginal annotation is to be found in texts aimed at school children: in particular I have been looking at a series of mid to late sixteenth-century English-Latin dictionaries, designed to facilitate Latin prose and verse composition, such as those originally compiled by Richard Howlet and John Withals. Arranged topically, rather than wholly alphabetically, (difficult in an era before standardized English spelling), these dictionaries group likely vocabulary along themes such as ‘Trees’, ‘Animals’ and ‘Architecture’, or historical and legendary characters and place names. As such, they have not attracted the same degree of critical attention as dictionaries of the sort we might recognize today, and represent something of a detour in linear histories of lexicography. But the marginalia in the Folger’s editions show that they were enthusiastically read, and often jealously guarded.

One aspect of early modern readership which strikes us afresh when we are confronted with a palimpsest of marginal notes and markings is the sharing and reuse of these texts, often many decades after they were printed. Messages and Latin tags record how they were passed between friends, and frequently include threats to the borrower if the book is not returned. Claims of ownership are made again and again by the same students, which evince the high stakes for possessing and retaining these works.

In addition, young readers were keen to record the names of their home towns. These references add clout to their claims of ownership and authority. But they also pinpoint a constellation of English readers, providing a sense of the wide geographical distribution of such texts. Using these proprietorial statements, we can begin to locate the dictionaries’ reach beyond the intellectual milieu of London’s bookselling hub, St Paul’s Churchyard, to which studies of early modern print are often confined.

So how did their owners use these books? The evidence suggests that they were read both earnestly and irreverently, haphazardly and in minute detail, and used for their intended educative purpose, as scrap paper, and everything in between. Tiny typographical errors are often corrected, implying remarkably close attention. Elsewhere, the worthy sententiae of the texts are subversively parodied: next to the axiom, Demon ipse crucem fugit vt malus vndique lucem, ‘The diuell himselfe from the crosse takes his flight,| As an ill bodie euery where forsaketh the light’ (sig. K6r), one daring reader of Withals’s 1599 Dictionarie (Folger 25883, Copy 2) has added the variant ‘Demon ipse crucem fugi[t] vt canis vn[dique] lardum’: the devil himself flies from the cross, as a dog flies from bacon…

Image: Richard Howlet’s Abcedarium (1552), Folger 13940. Photograph by Harriet Archer (2015), reproduced courtesy of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

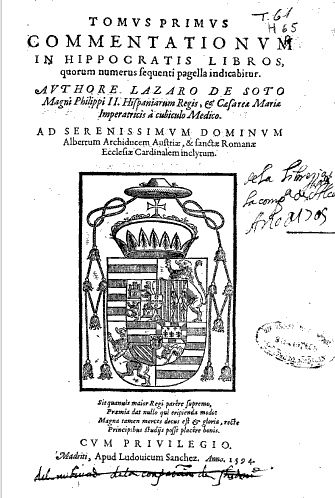

Brianne Preston, PhD candidate, History

I recently submitted my doctoral thesis that examined a Latin medical commentary by the Spanish court physician Lázaro de Soto. De Soto's served as the chamber physician to Philip II (1527-1598) and his sister Maria of Austria, Holy Roman Empress (1528-1603). His commentary, published in Madrid in 1594 and dedicated to Maria's son, Archduke Albert VII of Austria, was entitled Tomus primus commentationum in Hippocratis libros. Itexplored the Hippocratic text De locis in homine or Places in Man.

(Title-page taken from the copy held at the University of Alcala in Madrid)

One fascinating aspect which emerged whilst I was researching the field is that the genre of commentary was seen as a means of progressing the art of medicine. In line with the intellectual trend of humanism, de Soto, and other physicians like him, believed that a better medicine could be created by producing better translations and exegeses of ancient texts; studying and commenting on the ancient works of Hippocrates was seen as a means to better understand, and thus improve, medicine. De Soto expresses this by writing in his dedication "...it seems to me that not some new literary genre remains, but Hippocrates' new book, Places in Man, remains worthy for exegesis…" Whilst the genre of commentary itself is an ancient tradition, the words of Hippocrates, when better understood, will always produce new information. However, de Soto also used the genre of commentary to further his own agendas. For example, throughout the course of his work, de Soto demonstrates his erudition by citing an abundance of classical and contemporary sources, both medical and literary. Beyond just showing that he was smarter than the rest of the kids in the class, this was likely a bid by the physician to further his career in the court of Philip II. Additionally, de Soto uses his commentary to endorse Galenism, whose principles had been recently contested. He does this by, again, championing the ancient sources and by reasserting the validity of the humouralism - the understanding that the physiology of the body was controlled by fluxes and movements of the four humours. We have very little extant information about the life and career of Lázaro de Soto. We know a few basics, such as his 1571 employment at the casa real and his death in 1626, but through his commentary a wealth of information may be extrapolated about how he understood and practiced medicine. Moreover, his commentary stands as a case study of the practice of medicine and medical humanism in Renaissance Spain, thus providing a point of comparison for future research of medicine in the early modern era.

The Lives of Early Modern Queens Consort - Adam Morton (History)

What was life like for an early modern Queen Consort? Moving countries and cultures as a result of marriage, their role in life was to largely biological: to provide ‘an heir and a spare’ in order to secure the dynastic line of the current monarch. As part of the research team on a HERA-funded project – ‘Marrying Cultures: Queens Consort and European Identities 1500-1800’ – I've been investigating the paradoxes and contradictions inherent within the position of consort. At once foreign and part of the crown, she retained loyalties to her dynastic ties as she was intimately involved in the politics of her adopted state. Often of a different religious faith to her husband, and sometimes not sharing a common language, consorts had to adapt to sometimes hostile environments and became skilled practitioners of the arts of soft power. In many cases these women wielded considerable influence, and the ‘Marrying Cultures’ team’s research has focussed on their role as agents of cultural transfer: by bringing new ideas, fashions, artists and musicians to her new court, the consort often injected elements of culture in to her adopted country. In some cases, these foreign elements were absorbed to become beacons of national identity.

http://www.marryingcultures.eu/

Catherine of Braganza, by Sir Peter Lely (1663-65)

Catherine of Braganza is the subject of my research on the project. In the video below the project leader, Helen Watanabe-O’Kelly (Oxford) and I speak about the role of sex at court with specific reference to Catherine.

This public lecture was filmed at a sixteenth-century castle in Skarhult, Sweden, during an exhibition celebrating the women who had lived there over six centuries.

August 2014 - Magnus Williamson (Music) lectern singing at the Med-Ren Conference, Birmingham

Search for a medieval image of people singing, and you will probably find a depiction of robed clergy standing in a small cluster around a lectern; all singers face one choirbook, keeping time by the discreet waving or tapping of a hand – quite different from modern concert hall configuration.

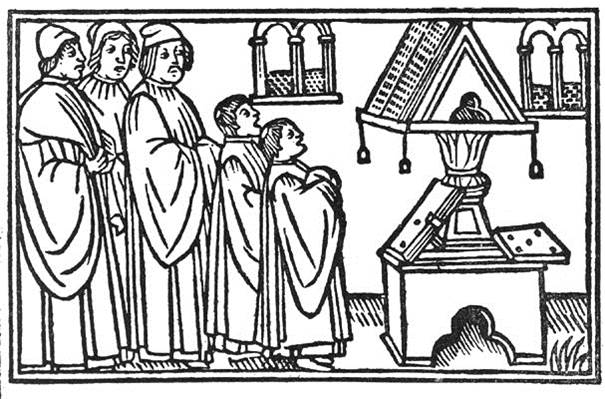

MEMS has its own lectern, a nineteenth-century reproduction of the simpler kind of stand illustrated in fourteenth-century psalters and service books. Increasingly elaborate and sturdy choirbook lecterns can be found in later fifteenth century, including a famous depiction of the French Chapelle royale, directed by the composer Jean Okeghem. Here is one of the earliest printed depictions of lectern singing: note the rotating reading desk and the lead weights for holding books open:

Although lectern singing died out in England sometime after 1530, it persisted in parts of continental Europe until the 19th and 20th centuries. Why was it so long-lasting? During a recent AHRC-ESRC research project, the Experience of Worship, experiments with lectern singing yielded dramatic results in terms of blend, ensemble, intonation and togetherness (in several senses of the word).

With financial support from EECM, we took this a step further at this year’s Medieval and Renaissance Music Conference in Birmingham, where the Binchois Consort (directed by Prof. Andrew Kirkman) performed the Epiphany hymn Hostis herodes impie with polyphonic verses by John Sheppard (d. 1558) alternating organ versets by an anonymous contemporary. This experiment points the way towards a full spatial realisation of the Epiphany, the great crown-wearing apex of the royal calendar, as celebrated in Mary Tudor’s Chapel Royal Mary Tudor. Click to listen:

Northumberland Place-names (Diana Whaley, English Literature & Language)

A few days ago I found myself lying on my stomach looking down on a 30-metre whinstone sea-cliff, white with nesting kittiwakes and their guano. At its foot, breakers were foaming and spuming in and out of a small low cavern in an angle of the cliff, lit by a bright July sun and driven by a stiff onshore wind. And all in the name of academic research!

(Kittiwakes on Gull Crag. Photo by Ian Whaley)

Fieldwork is one of the many pleasures of place-name work, and this visit to Gull Crag and Rumble Churn, on the north side of the Dunstanburgh Castle headland, Northumberland, was part of an investigation into the vocabulary of the names on a small stretch of coast within a much larger project of compiling a dictionary of Northumberland place-names for the English Place-Name Society (projected publication 2019). Beyond that, all new work in place-names draws on, and contributes to, a very large body of comparative material which enhances our understanding of types and processes of naming, and their linguistic and historical significance.

(Gull Crag and Rumble Churn. Photo by Diana Whaley)

Gull Crag and Rumble Churn are just two of the minor topographical names on this stretch of coast that appear transparent but still have stories to tell. Gull Crag is what it seems (kittiwakes are a species in the gull family), and the word crag occurs in names of many northern outcrops, but the word originates in Gaelic and the route by which it percolated into Northumberland is an unsolved question – one of scores that have barely been asked so far. Rumble Churn has both common and rare features: many place-names are metaphorical, applying terms for ‘cup, bowl, door’ etc. to natural features, but few make reference to sound. I was curious to visit the site to test the rumble and to see exactly where it is, since Rumble Churn is a name that has moved.

Rumble Churn originally referred to a longer inlet on the south-east of Dunstanburgh Castle, but on the 1897 Six Inch Ordnance Survey map that inlet is named Queen Margaret’s Cove (a probably spurious allusion to Queen Margaret of York’s visit to Northumberland during the Wars of the Roses), while Rumble Churn is shown in its present, northern location. In fact, the original site is a more convincing rumbler, and eighteenth-century visitors enjoyed being terrified by it.

(Queen Margaret's Cove - the original Rumble Churn. Photo by Ian Whaley)

.jpg)

The surf foams and roars in it, and the large round boulders at its inland end rumble when the tidal swell is strong, nicely matching the definition in the Scottish National Dictionary entry for the verb and noun rummle: ‘Rummlekirns — Gullets on wild rocky shores, scooped out by the hand of nature; when the tide flows into them in a storm, they make an awful rumbling noise; in them are the surges churned’; various usages of rummle involve loose stones.The Scots form kirn/kern is matched in Rumbling Kern, three miles south of Dunstanburgh, so the Northumbrian pair of Rumble Churn and Rumbling Kern seem to represent rivalry between standard and dialect forms, also seen in the alternation between big and muckle in local names. This is part of a much bigger linguistic picture: Northumberland has a rich dialect vocabulary much of which is more akin to Scots than to other English dialects, and the place-names can add a great deal to our knowledge of it – as well as being a grand excuse for lying on crags watching the waves.

Finally and briefly, the name Dunstanburgh is ‘the stronghold at Dunstan’, from nearby Dunstan (‘hill-stone’) and Old English burh ‘stronghold, fortified place’ (common in place-names such as Edinburgh, Middlesborough, Salisbury and dozens of others) OR its Middle English descendant or reflex, burgh. The name is first recorded in 1313-14, precisely the time when the castle, now a massive, stark ruin, was being built by Thomas, Earl of Leicester. If the name was given in the Old English period it could refer to Iron Age or Roman defensive structures for which there are traces of evidence, but if given c. 1313, the naming would have expressed the same political dynamic as the castle itself, as a defiant response to Bamburgh to the north, a stronghold of Thomas’s cousin and rival, Edward II.

(Dunstanburgh Castle from Embleton Bay. Photo by Ian Whaley)

June 2014 - Magnus Williamson (Music) on his Tudor Partbooks project

The year 2014 sees an exciting new AHRC-funded project come to Newcastle: Tudor Partbooks: the manuscripts legacies of John Sadler, John Baldwin and their antecedents. Magnus Williamson, MEMS member, is principal investigator; the co-investigator is Julia Craig-McFeely of www.diamm.ac.uk and the Faculty of Music, Oxford) as co-Investigator. We are delighted to announce the recent election of a PhD student, Daisy Gibb, and appointment of a post-doctoral RA, Dr Katherine Butler.

Tudor Partbooks has several aims, chief of which is to transform our understanding of (and access to) Tudor music manuscripts, an internationally important set of witnesses to Renaissance musical culture before and after the upheaval of the Reformation. We have already got to work on the project: the library of Christ Church, Oxford, have recently digitized the Elizabethan ‘Baldwin’ partbooks (Mus. 979-83) which will be published in facsimile once Tudor Partbooks have reconstructed the missing Tenor partbook. Polyphonic reconstructions will be provided by a collaborative team: get in touch with Magnus Williamson if you want to participate!

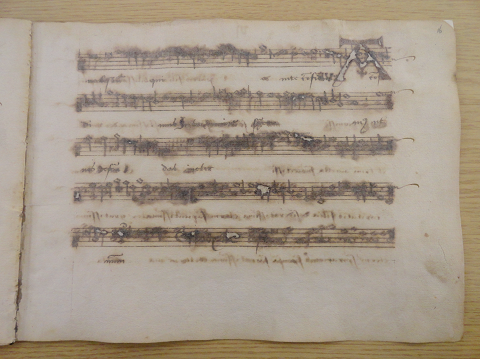

We’ll also publish a restored facsimile of the ‘Sadler’ partbooks which were copied by the Northamptonshire vicar and teacher, John Sadler around 1580; he was an assiduous calligrapher, but used a disastrously acidic ink mix whose corrosive effects, visible in the picture below, will be digitally reversed by DIAMM, returning the partbooks to a state last seen around the time that Mary Queen of Scots was executed in nearby Fotheringhay Castle.

One of the Sadler Partbooks (Bodleian Library, Mus. e.2, f. 16r) showing the corrosive (but digital reversible) effects of acidic ink

News: the project starts at the end of September, but work is now underway. Several manuscripts have already been digitized (GB-Ckc Rowe 316; GB-Och Mus. 979-83; GB-Ob Tenbury 341-4, for example); and the collaborative team has started work on reconstructing the missing Tenor partbook from the Baldwin set. An early version of one reconstruction (of William Mundy’s Veni creator spiritus), was piloted at the Birmingham Med-Ren Conference by the Binchois Consort, directed by Prof. Andrew Kirkman. Click to listen:

Stop press: project web site currently under construction: www.tudorpartbooks.ac.uk. In the meantime: http://research.ncl.ac.uk/sacs/icmus/projects/current#tudor.