May 2021

Historical data: The foundation for low-carbon technologies

Dr Alex Dickinson discusses the importance and challenge of working with existing geological data

Geological resources are likely to play a key role in decarbonisation of the UK economy. Geothermal energy can be harnessed to heat buildings and generate electricity, whilst underground reservoirs can be used to store hydrogen fuel and to lock away atmospheric carbon. Development of these novel technologies depends on detailed understanding of the ways in which heat and fluids move through geological formations beneath the British Isles and adjacent offshore regions. This understanding is vital to enable companies, investors, policymakers and regulators to identify optimum locations for underground infrastructure and to manage resource extraction in a sustainable way.

Our knowledge of subterranean geology is commonly based on measurements made in boreholes and on images that are constructed using sound waves (these images are known as seismic images). These observations can be used to develop three-dimensional computer models that show the suitability of different locations for geothermal heating, hydrogen storage or carbon sequestration. Acquisition of borehole measurements and seismic images is, however, extremely costly, and often unaffordable for technologies that have unproven economic value. Instead, it is more economical and efficient to use existing data. Measurements of properties such as subsurface temperature and rock composition have been carefully recorded since at least the early nineteenth century for purposes as diverse as mining, extraction of oil and gas, construction of irrigation works, disposal of nuclear waste, and scientific research. Making full use of these historical records is, however, hindered by three challenges:

- Data are difficult to access. Measurements are contained within a range of scientific articles, commercial datasets and government reports. Many of these sources can only be accessed by private companies or by a limited number of research institutions. Those records that are publicly accessible are often not available in a digital format.

- Data are not standardised. Existing measurements were acquired for a wide range of purposes. Each of these purposes had different requirements for measurement accuracy and resolution, and data are archived in different formats.

- Digitisation is not community-led. Teams of researchers are spread across universities, scientific institutes and private companies. These dispersed teams are not effective in driving a common agenda for the digitisation of data and sharing of resources.

These challenges limit the ability of researchers to provide high-quality, novel insights into the potential role that geological resources can play in supporting the UK’s move to low-carbon technologies. Possible solutions include:

- Making all existing data publicly available. Government agencies, universities, scientific publishers and private companies could be required to deposit all historical data in open-source archives (see, for example, NOPIMS).

- Compiling standardised databases of existing measurements. Until a few years ago, standardization and compilation of all existing data would be an almost unthinkably arduous task. The rapid adoption of digital technologies, however, makes it possible to construct easily searchable, centralised databases. These resources would dramatically reduce the time that researchers currently spend on finding, copying and formatting data.

- Coordinating data-management plans. Significant improvements in research efficiency could be fostered through establishment of consortia that span multiple public and private organizations. These consortia would focus on establishing schemes for acquisition, processing and storage of data.

Work has already begun on aspects of these solutions. For instance, the British Geological Survey provides an online database that gives details of more than 1.3 million boreholes across the British Isles, and the UK Onshore Geophysical Library houses over 9,000 seismic images. Further development of these initiatives will require highly collaborative and focused conversations between private enterprise, public institutions and government. If the UK is to reach its net-zero ambitions, it is worth starting these conversations.

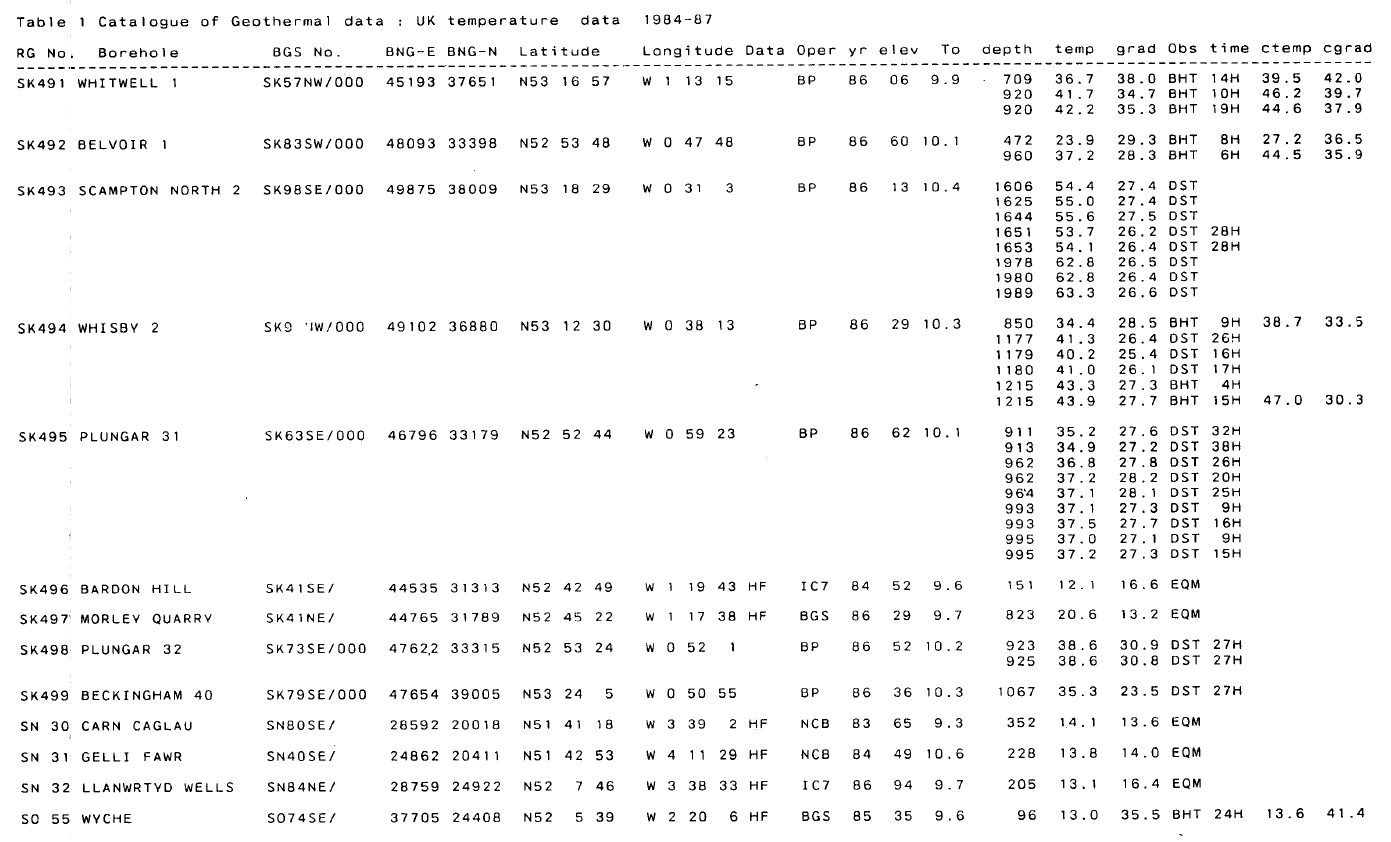

Many useful geological records are housed in printed reports that are not publicly available. Source: Catalogue of geothermal data for the land area of the United Kingdom (third revision), published in 1987 by the British Geological Survey.