The Edition

Editors' Handbook

MSWord 1,886Kb

Editors' Handbook

MSWord 1,886Kb

The Editors' Handbook for the Thomas Nashe Project is available here. This is a work-in-progress and subject to further revisions. If you have any suggestions please email Jennifer Richards at: jennifer.richards@ncl.ac.uk

Annotation Essentials

MSWord 3,306Kb

Annotation Essentials

MSWord 3,306Kb

Nashe's prose is incredibly rich, and needs clear, detailed, but concise annotation. Here you can read our current annotation policy.

We will continue to update this page with more information about the texts included in the Collected Works of Thomas Nashe over the following year. In the meantime, you can read our introductions to the texts and view some open access resources available now on: 'Anatomie of Absurditie', 'Pierce Penilesse', 'Christs Teares over Jerusalem', 'Terrors of the Night', 'Have with you to Saffron Walden', 'Nashe's Lenten Stuffe', and 'Summer's Last Will and Testament' below.

Anatomie of Absurditie (1589)

Kirsty Rolfe introduces her text for the Nashe Edition:

Kirsty Rolfe introduces her text for the Nashe Edition:

The Anatomie of Absurditie, Nashe’s earliest extant work in English though not his first to appear in print, was registered to the stationer Thomas Hackett on 19 September 1588, but was not printed until late 1589, after his preface to Robert Greene’s Menaphon. It was probably written before Nashe arrived in London from Cambridge in 1588, and intended to be a calling card for a young writer on the make, demonstrating his rhetorical skill and command of learned sources.

The book’s practical success is difficult to gauge. Nashe managed to secure, in Hackett, a respected publisher, but his association with Charles Blount, the dedicatee, does not seem to have continued. Its success as literature has, on the other hand, been generally dismissed by critics: Lorna Hutson deems it ‘brittle and tedious’, while Charles Nicholl describes it as ‘clever, shallow, and tritely “Euphuistic”’ (Hutson, p,67; Nicholl). Euphuism refers to a style of complex, lyrical prose drawing on John Lyly’s Euphues (1578). Throughout the text, Nashe draws on and patches together classical and contemporary styles and sources, leading both Hutson and McKerrow to dismiss the work as derivative (Hutson, pp.67-8; McKerrow, IV, pp.1-2).

The ‘absurditie’ the text sets out to ‘anatomise’ is rather nebulous; Nashe begins with an extravagantly misogynistic attack on women, but moves on swiftly to concern with education and with the rewards (or otherwise) of wit. Throughout, however, most of Nashe’s ire is reserved for contemporary writers. He attacks poets who ‘[blaze] Womens slender praises’, taking a line familiar to anyone who frequents internet comment sections: accusing them of praising women only in order ‘to be more amiable with their friends of the Feminine sexe’ (sig. A2r). He ridicules hack versifiers, mocking ‘what scambling shyft’ the writer of Bevis of Hampton ‘makes to ende his verses a like’ (sig. C1r). In particular, he criticises those ‘who make the Presse the dunghill, whether they carry all the muck of their mellancholicke imaginations, pretending forsooth to anatomize abuses, and stubbe up sin by the rootes’ (sig. B1v). Nashe’s target here is Philip Stubbes’s The Anatomy of Abuses (1583), and what he represents as Stubbes’s intolerance, hypocrisy, and misuse of biblical sources. His jibe demonstrates both the essentially conservative nature of The Anatomie of Absurditie’s satire, and its close engagement with the literary market in which the young writer hoped to make his mark.

Works cited

Lorna Hutson, Thomas Nashe in Context (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989)

R.B. McKerrow, The Works of Thomas Nashe, vol. IV (London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1908)

Charles Nicholl, ‘Nashe [Nash], Thomas (bap. 1567, d. c. 1601), writer.’ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2004)

Prefaces to Menaphon (1589) and Astrophel and Stella (1591)

We'll be adding something here soon!

The anti-martinist tracts (1589-90)

We'll be adding something here soon!

Pierce Penilesse his supplication to the devil (1592)

Pierce Penilesse is voiced by one of Nashe’s alter egos. The name references ‘Piers Plowman’, but this is a satirical persona without paid employment, trying – unsuccessfully – to make a living by writing. Down on his luck, worried where his next meal is coming from, and railing against a world where patrons prove ungrateful and seemingly less talented people thrive, Pierce pens a supplication to the devil in a desperate bid to change his fortunes, and – above all – to liberate money from the ‘uncharitable cormorants’ who are hoarding it. The ‘Paper-monster’ he creates comprises the bulk of the book: a scabrous, scattergun attack on all sections of Nashe’s society, at home and abroad, offering a kaleidoscope of contemporary culture, from Elizabethan drinking games or the topography of London’s sex industry, to a commentary on late Elizabethan theatre.

Structured as a parade of the Seven Deadly Sins, the targets of Pierce’s supplication are many and various, from usurers (charging excessive interest and luring feckless young men into debt) to pedantic preachers, subjecting their congregations to excruciatingly dull sermons botched together from other theologians’ works. At times, Pierce’s/Nashe’s invective is specific enough to suggest that it’s aimed at identifiable people, as with his mockery of the ‘upstart’, a social-climber who conceals their humble origins in the wool trade, instead boasting pretentiously of their foreign travels and writing derivative love poetry to their ‘yealow fac’d Mistress’. Famously, one person who did (correctly) recognise himself and his family amidst the diatribe was the Cambridge scholar Gabriel Harvey, and Pierce Penilesse was the opening shot in a protracted literary skirmish between the two men, which culminated in the works of both being named amongst the list of proscribed books in the Bishops’ Ban of 1599.

Pierce Penilesse ends with conversation between Pierce and a servant of the devil (a man who makes money by bearing false witness in law trials), who’s been commissioned to deliver the supplication to his master. Pierce interrogates this companion about the nature of devils, a conversation that contains a catalogue of devils (a miniature grimoire) and a beast-fable that covers similar territory to Leicester’s Commonwealth, a libellous attack on Elizabeth I’s favourite, Robert Dudley (who’d died four years before Pierce Penilesse).

Nashe's best-seller Pierce Penilesse went through five different editions in three years. To discover the changes Nashe made to his work, click here to read Kate De Rycker's post on the original copies held by our project partners, the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Strange Newes (1592)

We'll be adding something here soon!

Choice of Valentines (c.1593) and other short poems

We will be adding more information here soon!

Christ's Teares over Jerusalem (1593)

Chris Stamatakis introduces his text for the Nashe edition:

Chris Stamatakis introduces his text for the Nashe edition:

“It is a common and not always unspoken feeling among writers on Nashe,” Philip Schwyzer remarks, “that Christ’s Tears should not have been written at all”. Part satire, part parable, part sermon, part commentary on sermons, Nashe’s Christs Teares – an apocalyptic, sui generis cabinet of curiosities – has bewildered modern readers yet was clearly noteworthy enough in its time to be reissued (slightly revised) a year later and to be referenced by Nashe’s contemporaries.

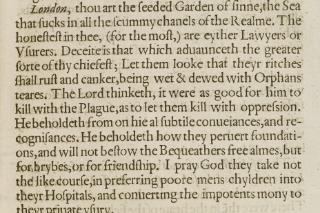

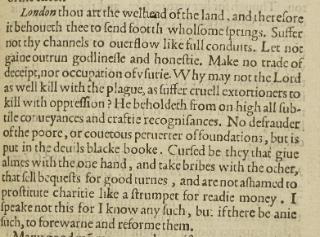

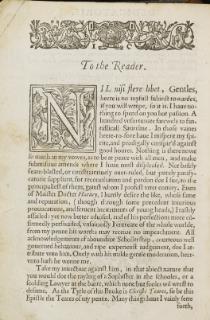

For all its penitential fervour as a “comparatiue admonition” lamenting the fall of Jerusalem and urging a plague-ridden London to repent to escape similar divine wrath, Christs Teares is a recognisable Nashean product. In a spirit of literary inventiveness and baroque theatricality, it freely juxtaposes voices, registers, genres, modes, and perspectives. Its pages are visually noisy: they are dotted with biblical snippets and marginal citations; filled with repeated, italicised keywords (“gather”, “desolation”, or, wonderfully, “eccho”) that tumble through successive paragraphs; and peppered with inverted commas that run down some margins. In its very appearance, Nashe’s text playfully reflects, and reflects on, what it describes as “a banquet of broken fragments of Scripture”. This polyvocal jeremiad forms an important part of the Nashe canon, for both biographical and literary reasons. One particularly vituperative, inflammatory passage in the first issue (1593), beginning “London, thou art the seeded Garden of sinne” (sig. X3rv), seems to have prompted Nashe’s arrest and imprisonment, and necessitated the publication in the second issue (1594) of a toned-down version (although the offending passage was reinstated in 1613!). The 1594 issue also features an additional preface “To the Reader” in which Nashe renews his attack on his long-standing antagonist Gabriel Harvey.

In this same 1594 preface, Nashe explicitly draws attention to one of his trademark stylistic features – his neologisms, “boystrous compound wordes”, and habit of “ending my Italionate coyned verbes all in Ize”. Christs Teares is a lexicographic trove of coinages and first citations, including (fittingly) the word “multifarious”. The text in many ways resembles an experiment in fusing words together to form a new polyvocal compound, a celebration of linguistic plenty, and a demonstration of Nashe’s verve for exceeding the customary borders or limits that demarcate or define a thing. The result is a compelling, multifarious hybrid that seems to announce a new type of writing.

Terrors of the Night (1593-4)

Kate De Rycker introduces her text for the Nashe edition:

Kate De Rycker introduces her text for the Nashe edition:

On first inspection, The Terrors of the Night is an essay about nightmares, but go below the surface and you will discover a vividly written work which foreshadows William Shakespeare’s unsettling ‘Queen Mab’ speech in Romeo and Juliet (c.1594). Its speaker, Mercutio, shares Nashean traits: quick-witted, sceptical, with a talent for getting into trouble and a barely repressed disgust for female sexuality. Nashe vacillates between contemporary opinions on the cause and meaning of dreams. Are people more susceptible to supernatural forces at night, or do dreams reflected the interior fears of the subject? Are dreams divinely inspired, or essentially physical in origin? Throughout this essay, Nashe shifts between nostalgia for the old-wives tales of divination, and scepticism that dreams can prognosticate the future. No wonder that Sigmund Freud, who had been sent a copy by the psychoanalyst Ernest Jones in 1912, sent the text to the Zentralblatt für Psychoanalyse as an example of “psychologically significant anticipations of psychoanalytic studies of dream and nightmare.”

The composition of The Terrors of the Night had a long gestation. Nashe first started to write it in February 1593 “in the Countrey some threescore myle off from London; where a Gentleman of good worship and credit falling sicke, the verie second day of his lying downe, hee pretended to have miraculous waking visions.” Back in London Nashe’s publisher, John Danter, registers this new work in the Stationers’ Register as ‘Terrors of the Night, a discourse of apparisions’ on the 30th June 1593. And then silence. Nashe’s controversial Christ’s Tears over Jerusalem is published that autumn, and he is sent to Newgate prison as a result. Luckily for Nashe, his patron Sir George Carey pays for his release and invites Nashe to spend Christmas with his family at Carisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight. It was after this visit that Nashe decided to substantially revise The Terrors of the Night, shifting its focus onto the interpretation of dreams which was one of the ‘games at Court’ that winter. Nashe would dedicate his augmented text to the daughter of the family, Elizabeth Carey, and write effusively of the hospitality he had received. Meanwhile, his novella The Unfortunate Traveller would be published (twice) and Danter would have to register the substantially altered text for a second time as ‘Terrors of the Night, an apparision of Dreames’ on the 25th October 1594.

Teaching The Terrors of the Night with Perry Mills

The Terrors of the Night is often described as having a complicated and digressive style, but on a visit to see our partners Perry Mills and his students at King Edward VI School in Stratford-upon-Avon, the Nashe team discovered that reading Nashe's prose aloud can bring new life to this ghostly text. To hear a recording made by our partners Testbed Audio, click here.

Performing Prose: Terrors at The Sam Wanamaker Playhouse

On the 20th May 2017, the Nashe Project hosted a 'Read Not Dead' reading of Nashe's The Terrors of the Night by candlelight at the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse. Because 'Read Not Dead' usually works with underperformed plays, the editor of this prose text, Kate De Rycker, collaborated with the director Jason Morell to produce a new script, ready for performance, which you can read by clicking here.

The Unfortunate Traveller (1593)

We will be adding more things here soon!

Dido Queene of Carthage (with Christopher Marlowe c.1588, published 1594)

We will be adding more things here soon!

Have with you to Saffron-Walden (1596)

In this tour-de-force, Nashe experiments with the dialogue form and the layout of the page to present his final attack on his rival, Gabriel harvey. For a guide to Nashe's use of illustrations and his subversion of print conventions, click here to read Kate De Rycker's guide to a copy held at the Folger Shakespeare Library.

In this tour-de-force, Nashe experiments with the dialogue form and the layout of the page to present his final attack on his rival, Gabriel harvey. For a guide to Nashe's use of illustrations and his subversion of print conventions, click here to read Kate De Rycker's guide to a copy held at the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Nashe's letter to William Cotton (c.1596)

We will be adding more information here soon!

Nashe's Lenten Stuffe (1599)

Andrew Hadfield introduces his text for the Nashe Edition:

Andrew Hadfield introduces his text for the Nashe Edition:

Lenten Stuffe is probably Nashe’s last work (Summer’s Last Will was published later but written in 1592). Written in the wake of the scandal over The Isle of Dogs, Lenten Stuffe opens with the author recounting his flight from London to Great Yarmouth. Yarmouth is praised as a champion of liberty, perhaps with some irony as Nashe was born in Lowestft, its great rival. The work celebrates the significance of the (preserved) red herring, an abundant foodstuff which became a staple of many Europeans’ diets and, therefore, a valuable commodity which made the Suffolk fishing ports wealthy and politically powerful.

Lenten Stuffe is a mixture of hard-headed economic analysis and wild flights of fancy, which imagine the dried herring travelling the world like a flying fish as its acknowledged ruler. The work combines a variety of styles and registers, from satirical mock-epic to elegy and encomium, linking literary modes to styles and types of history. One section imagines Marlowe’s Hero and Leander as a story of two doomed lovers transformed into a red herring and a ling. Another describes the travels of Sir William Harbourne, ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, and native of Great Yarmouth, sustained by red herring.

Charles Nicholl's on Lenten Stuffe

You can read an excerpt from Charles Nicholl's biography, A Cup of Newes (1984) on Lenten Stuffe and the fall-out from The Isle of Dogsby clicking here.

Summer's Last Will and Testament (c.1592, published 1600)

Bart Van Es introduces his text for the Nashe Edition:

Bart Van Es introduces his text for the Nashe Edition:

This is Nashe’s only surviving sole-authored drama. First performed before the Archbishop of Canterbury in September or October 1592, Summer’s Last Will is an allegory on the changing of the seasons filled with songs, formal debates, spectacular costumes, and dances. The plot is simple: Summer is dying and in the course of the play he must assess the condition of his estate before passing it on to an heir. In various ways, the work is untypical of Nashe’s output. In contrast to the rest of the canon this is a fairly conventional, non-commercial, private entertainment and it went unpublished until 1600, shortly before or immediately after the author’s death.

The presence of an on-stage presenter, Will Summers, however, makes the work more complicated than it first seems. Nashe’s presenter is the ghost of a famous jester at the court of Henry VIII, and through him the author raises questions about the success or failure of the drama, about the presence of plague (which threatens the harvest spirit), about the place of festive excess versus frugality, and about the duties of rich patrons towards the poor. Always present on stage, Will Summers is a riddling and questioning inversion of Summer’s Will.

Charles Nicholl on Summer's Last Will

To read an excerpt from Nicholl's biography A Cup of News (1984) in which he discusses the original performance of this 'show' at the Archbishop Whitgift's palace in 1592,please click here.

Edward's Boys perform Summer's Last Will

To see a recording of Summer's Last Will by our project partners, Edward's Boys, as well as reading reviews and hearing cast commentary of the play, you can click here.

Doubting Thomas: Nashe's Dubia

We will be adding more information here soon!