Guide to Folger's Have with you to Saffron Walden

This is the first of our guides to the digitised copies of Nashe held at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington D.C., one of our academic partners. At the bottom of this page, you can view one of the Folger’s copies of Have with you to Saffron-Walden (1596), together with the woodcut of Nashe in The Trimming of Thomas Nashe (1597), and a few pages from John Danter’s edition of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet (1597).

Many of the Folger’s resources are available for public users to view open access, via their Digital Image Collection which holds over 70,000 images of books, manuscripts, costumes, and many more Shakespearean artifacts. This catalogue is searchable on http://luna.folger.edu, and anyone can register in order to save and share selections from these digitised images, as we have done to show you around their copies of Nashe.

Features to look out for:

As you look through the pages of this take-down by Nashe of his adversary Gabriel Harvey, you may notice some of the following interesting features of this pamphlet, which our editorial team will have to transform into a modern edition:

‘Found’ objects in the text

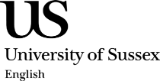

In this text, Nashe plays with the idea of reproducing other types of texts usually found in the public sphere in his pamphlets. In his mock dedication to the barber Richard Lichfield for example, Nashe pretends to provide Lichfield with “A Grace…[o]n behalfe of the Harveys” (his public enemies and the targets of this pamphlet) which he asks Lichfield to ‘put up’ somewhere in his barbershop.

At the bottom of this ‘Grace’ is an ornamental frame, which has been left empty, which may simply be a way for the printer to fill space, but Nashe goes on to explain that he left that empty frame there ‘Purposely’ so that anyone who sees this and agrees with him that the Harvey are idiots, can use it to fill in their own ‘sentences’ against the brothers, and join Nashe in ‘unhandsoming’ them.

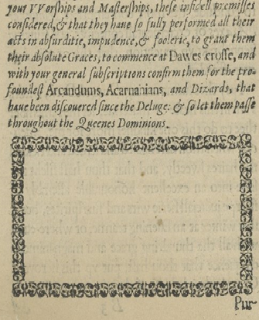

Elsewhere, Nashe reproduces some of Harvey’s words in block Roman capitals, in order to give them the appearance of the marketplace sign of a dyer, in order to accuse Gabriel Harvey of selling out:

For more on this, see Neil Rhodes’s article on Nashe and the modern critic of media theory, Marshall McLuhan, here: http://journal.oraltradition.org/files/articles/24ii/07_24.2.pdf

The Printer’s Devices

These are the motifs used to decorate early printed books which, as well as showing the embellished nature of Elizabethan texts that we are unused to seeing in our modern editions, can also give us clues to how these various devices identify different printers, and how they were passed on through different generations.

For example, these two devices, the owl:

and the two men:

belonged to the printer of many of Nashe’s works, John Danter, and reappear in many of his other works (such as Nashe’s Terrors of the Night, 1594), including some copies which we would otherwise not know were printed by Danter from the lack of information on their title pages. The owl device may have been an anti-Papal reference to a story from John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments in which an owl (which was understood to be a bad omen in this period) caused a disturbance in the Papal Council.

The device with the two men used to have Danter’s initials (J.D) in the middle, but according to J.A. Lavin, these dropped out during the printing of Robert Wilson’s The Cobbler’s Prophecy (1594). You can read Lavin’s article on Danter’s devices here: http://xtf.lib.virginia.edu/xtf/view?docId=StudiesInBiblio/uvaBook/tei/sibv023.xml

A year after publishing Have with You to Saffron-Walden, Danter would use both of these devices on the 1597 edition of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, as well as a woodcut for its title-page, which he had previously used for Nashe’s Strange Newes (1593) and Terrors of the Night, depicting Opportunity standing on a wheel floating in the sea, with the motto ‘aut nunc aut nunquam’ (now or never).

You can see the relevant images from Danter’s Romeo and Juliet at the end of the Have with You to Saffron Walden photographs at the bottom of the page.

These devices were passed on after Danter’s death to another printer, Simon Stafford, who published Nashe’s Summer’s Last Will and Testament (1600) and used the ‘Opportunity’ woodcut on its title-page.

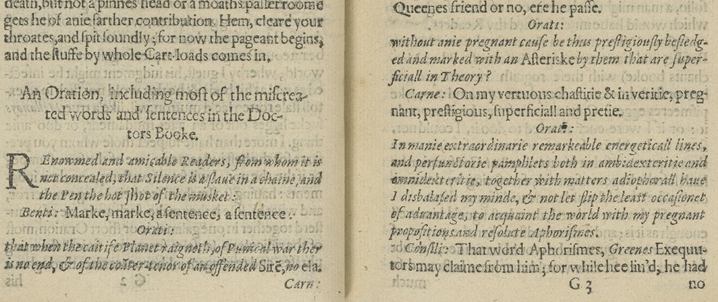

Representing different voices

Nashe regularly represents competing voices in his texts, but Have with you to Saffron-Walden is probably the best example of this. For example, while Nashe uses the margins to explain certain words, he subverts the reader’s expectations by explaining everyday practices and objects– like the advertisements put up on door posts or the napkins used by barbers– rather than writing conventional citations of biblical or foreign texts.

-215x320.png)

He also uses the margins as a space in which he can give a conspiratorial and literal ‘aside’, to his reader:

-320x110.png)

Nashe also presents his attack on Harvey in dialogue form, and in the Letter to the Reader asks us to imagine that he and four of his friends are meeting in a corner of the upmarket Blackfriars area of London, to pick apart Harvey’s previous assaults on Nashe, Pierces Supererogation and New Letter of Notable Content (both 1593).

Nashe alternates between italics and roman type to indicate when he is speaking in his own voice, or in the voice of one of his interlocutors, and when they are reading aloud certain sections of Harvey’s writing, which the various speakers repeatedly interrupt.

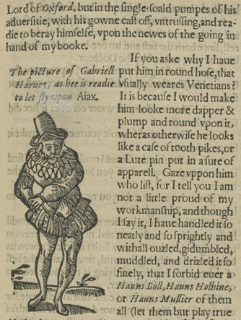

The woodcut of Harvey

Probably the most noticeable feature of this text is the ‘portrait’ of Harvey which Nashe claims to have created himself, though it seems likely that this woodcut is taken from an already existent woodcut of a generic man, especially as Nashe has to explain why he has presented his opponent in a different costume to Harvey’s, who usually wears 'Venetians', or knee-length breeches.

Above the woodcut is the description of Harvey ‘as hee is readie to let fly upon Ajax’ which is a pun on the word for a toilet, ‘A-jax= a jakes’, and was itself taken from the title of John Harington’s The Metamorphosis of Ajax (1596) which describes a precursor to the flushing toilet. Nashe is portraying Harvey here as being so scared by Nashe’s attack that he runs to the jakes.

The writer of a response to this text, called The Trimming of Thomas Nashe (1597) because it was presented as a response to Nashe by the barber Richard Lichfield, contains an even larger woodcut portraying Nashe in manacles, after his involvement with the Isle of Dogs scandal. This image of Nashe would itself be recycled and re-appears in a ballad ‘My Bird is a Roundhead’ from 1642, which you can read about in ‘Blogging the Renaissance’ http://bloggingtherenaissance.blogspot.com/2006/04/thomas-nashe-roundhead.html

We’ll be featuring the brilliant Trimming on this website soon, but till then, you can take a look at the Folger’s copy of Nashe’s caustic attack on the Folger's LUNA page or in the slideshow below.

These images are used by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library under a "Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License"