Blog

Archives Unlocked – A NUHRI/History event at Tyne and Wear Archives

Tyneside is a region rich in the history of environmental destruction and environmental concern. As one of the chief powerhouses of the industrial revolution, Newcastle and Gateshead are full of signs of extractive histories and stories of natural disasters, green initiatives, and the ever-present importance of the River Tyne. Public health initiatives have also featured prominently in the history of our region, ranging from slum clearances to the great “1000 Families” project. These histories of environment and health are reflected in the collections of the Tyne and Wear Archives, now housed in a former Co-op building on Blandford Square.

In October 2022 a group of around 14 MA and PhD students studying History at Newcastle University visited Tyne and Wear Archives in the company of Dr Alison Atkinson-Philips and Dr Shane McCorristine. This was organised and funded by NUHRI in conjunction with Alison, Shane, and Lizzy Baker at Tyne and Wear Archives. The visit occurred as part of Induction Week for the incoming postgraduates in the School of History, Classics and Archaeology, and was an opportunity for incoming students to learn about the work of the archivists and the collections available to them to consult.

The day opened with a warm welcome from Lizzy Baker and Carolyn Ball. They reflected on how enjoyable it was to meet people after a Covid-impacted number of years. They outlined some of the key collections and resources available to students and researchers in the archives. We then turned to two presentations on how the collections have benefited researchers. Joe Redmayne, a PhD student in History, reflected on his time researching and working in the archives as part of his project looking at the history of racial violence and industrial militancy in Newcastle. Because Joe was so reflexive about his research, it was clear his time in the archives was something that not only benefitted him, but also something which benefitted the institution.

Next up was Shane McCorristine who introduced the “In/sanitary Tyneside” project. In the summer of 2022 Shane recruited four interns from History to work on the history of sanitation in Newcastle-Gateshead. Funded by NURHI, the interns – Seren, Luke, Rachel, and Dan – have been researching Tyne and Wear’s collections relating to public health, nuisance reports, accounts of pollution, and the history of public toilets. These are histories which are at the intersection of the medical and environmental humanities, and the collections at Tyne and Wear are crucial in advancing one of the key objectives of the Environmental Humanities Initiative – to connect researchers with local institutions. The outputs of this project will be shared in late 2022.

"The event in progress"

Following the presentations, the staff and students split up into groups and were able to choose between several activities. These included an introductory session to microfilm, a chat with a specialist archivist on subjects of interest, and an opportunity to consult bound catalogues covering the whole collection. The most exciting activity, however, was the “behind the scenes” tour where Lizzy took small groups into the stacks, explaining the system of storage and the miles and miles of materials housed in the building. The groups viewed items ranging from a medieval town charter for Newcastle to teddy bears from the Fenwick collection.

Throughout the day staff and students were able to network with the staff at Tyne and Wear Archives and share their ideas for projects. For everyone involved this was a day when the archives certainly became unlocked! Thanks to Lizzy, Carolyn, Rachel and all the staff at the Archives for being so generous with their time; thanks also to Chris O’Keeffe and Clare Vint at NUHRI; and thanks to Alison and all the PGR students who made it an excellent networking event.

TEACHING GLOBAL ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY: A REFLECTION

Dr David Hope.

In this blog post, Dr David Hope, Lecturer in Eighteenth Century British History in the School of History, Classics & Archaeology, reflects on his experience of teaching environmental history and using digital Story Maps as a form of creative assessment.

How can historians engage students with the huge environmental challenges facing the world today? How can we provide a space for our students (and their instructors!) to reflect on the historical roots of present-day environmental crises? And what exactly is global environmental history anyway?

Last academic year I led a new second-year undergraduate module titled ‘Global Environmental History: From the Little Ice Age to Greta Thunberg’ that attempted to explore those questions. This was a team-taught module that many colleagues in History at Newcastle University were keen to establish, not least because aspects of our research encompass environmental history and we had few ways in our existing curriculum to use this research in the classroom. Perhaps most of all, we wanted to provide a module that could help our students to think critically about the environment and the historical processes that continue to contribute to the current climate and environmental emergencies.

We were also keen to adopt a creative form of assessment that would allow our students to develop new skills and provide a welcome alternative to the essay. We settled on the idea of a digital Story Map, a format that would allow students to produce an immersive, highly visual narrative of complex ideas, to develop their digital literacy, and to think more deeply about how to engage audiences in history research. In their Story Maps, the students had to reflect on the historical roots of a present-day environmental issue and/or a key theme in environmental history. We selected ArcGIS StoryMaps as the underlying platform, partly because our institution already subscribed to ArcGIS Online (which is needed to make an ArcGIS StoryMap) and because it is such an intuitive platform.

WHY GLOBAL ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY?

When designing the module, we wanted to ensure that it introduced students to the many ways environmental history can be approached and to make the most of the expertise in our section. We focused the module on the past 500 years so that we could examine a key period in which humanity has intensified its impact on global ecology, and used case studies from Britain, the Americas, Europe, the Indian subcontinent, East Asia, and beyond to offer wide-ranging perspectives on the history of human-environment relationships across the world. The global lens gave students the chance to draw parallels between different parts of the world and exposed them to very different ways of looking at human-environment relationships.

We covered topics such as the extraction and depletion of natural resources, species extinction, population growth, hunting and the origins of conservation, Enlightenment ideas about ‘improvement’, Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), environment and health, the history of ‘the park’, and many more. Many weeks inherently explored the impacts of colonialism, industrialisation, and environmental (in)justice. A more detailed breakdown of the module content can be found here

There were three assessments with the deadlines spaced across the module:

- One mid-term essay (1,800 words)

- A creative project plan (200 words, formative)

- A digital Story Map (2,000 words equivalent)

Since it is quite a different assessment to our standard formats, I created a specific marking scheme for the Story Map so the students could see how it fitted onto our standard marking scheme and to help them approach the task

SKILLS-BASED LEARNING

To support work on their assessments, the module had dedicated workshops that focused on a specific skill that the students needed to acquire, and so helped the students to understand how to go about ‘doing’ environmental history.

The first centred on historical sources for environmental history and utilised some of the collections on display in the Great North Museum: Hancock, including those relating to the history of whaling in Newcastle and the collecting of ‘exotic’ fauna. The second looked at maps as historical sources and historical mapping, with DigiMap used as the main resource. This encouraged the students to think about spatial relationships and the utility of digital mapping for historical research.

The third workshop introduced the students to the world of Story Maps. First, we got the students to explore some existing ArcGIS StoryMaps and reflect on what they liked (and disliked) about them, especially the elements they found engaging (and unengaging). We then discussed the power of storytelling and how this relates to history. We then let the students dive into ArcGIS StoryMaps and explore its features by making a Story Map about themselves, the university experience, or Newcastle. Since the platform is so intuitive, this ‘learn through play’ approach worked brilliantly and the students quickly grasped the concept. I had thought we might have to prepare a whole series of activities to get the students to the point of being able to make a Story Map but I was so glad to have a colleague point out that was totally unnecessary and would make things rather dull!

In the final workshop we reviewed what makes for an engaging Story Map and discussed effective ways to use the title and opening text. We then had the students share their idea of a Story Map in pairs with the forewarning that the next activity was for them to present their partner’s Story Map idea to the rest of the group so they needed to ask their partner lots of questions to fully understand their idea. The task worked a treat and from the buzz in the room it was clear that the students got a lot out of getting feedback from their peers.

CHALLENGES

The biggest hurdle was how to maintain a sense of coherence in the module content as it covered such a broad range of topics and geographies, and a decent timeframe (although a drop in the ocean in environmental history terms). I decided that as module leader it would be better if I served as an ‘anchor’ for the module by always being present for the workshops and taking most of the seminars. I spaced my topics throughout the module so I could routinely ‘check-in’ with the students and link the weeks together. I also did all the marking to ensure consistency.

When explaining the module to others, I was struck by how often they assumed that an environmental history module would be among the most popular enrolments, presumably an opinion formed from the prevalence of the climate and environmental emergencies in our daily lives and the traction among ‘young people’ in the Global Climate Strike and other forms of environmental activism. From my experience, history students tend to be rather conservative with their module choices, opting for topics that they have encountered during their studies at GCSE and A-Level and so it was no surprise to see that sign-ups were on the low side: environmental history (in the U.K. at least) barely features in the courses that students’ study prior to university.

In many ways the student numbers (12 in the end) provided a good starting point for getting the mechanics of the module right. Considering the large choice of modules that we offer our students in their second year, and that they have unlikely encountered environmental history before, it recruited a decent group in its inaugural year. Hopefully interest will build as it becomes more established and that it encourages students to undertake a final-year dissertation on an environmental history topic.

OUTCOMES AND STUDENT FEEDBACK

Despite my fears about the breadth of topics making the module disjointed, the module was a great success. Student feedback was overwhelmingly positive. Unsurprisingly, the Story Map assessment received the most praise and was described as ‘refreshing’, ‘engaging’, ‘fun’, and ‘a lot more interesting than writing an essay’. Several students also commented on how they felt that they had picked up some useful transferrable skills and commended the opportunity to choose their own topic to research. The variation in topics and geographic coverage was appreciated as ‘no one week was the same’ and even the team-taught teaching (often a bugbear with students) was praised for ‘bringing in different experts’.

From an instructor’s perspective, the quality of the work was high and student engagement was very good, although as is often the case, student attendance dropped off towards the end of the module, but seminar discussions were always lively and stimulating. I am now certainly more clued up about different approaches to environmental history and have a clearer sense of where my colleagues are working in this expanding field. Marking the Story Maps was particularly refreshing as the students really took to the format and came up with an expansive range of topics that showed some impressive independent thought.

I found the workshops one of most rewarding aspects of the module, which was largely due to the energy of the students and their questions. Attendance at those sessions was always high, and the students were keen to learn new skills that few other modules offer. I also rarely get the opportunity to co-teach with colleagues and that proved hugely rewarding in seeing how others teach and approach environmental history. That interaction has already led to a student summer internship (funded by the Careers Service JobsOC scheme) that explored the origins of the taxidermy on display in the Great North Museum’s Living Planet Gallery. I think it is a real asset that the module is team-taught as it means colleagues take collective responsibility for engaging students in environmental history rather than leaving it up to the ‘environmental historian’ in the department.

WHAT NEXT?

A key priority for 2022/23 is to introduce a fieldtrip to a local site(s) to give students the chance to ‘walk the landscape’ and reflect on the environmental histories of Newcastle and the surrounding area. Hopefully this will inspire some more Story Maps that locate the environmental history of Newcastle and the North East within a wider global context. It should also help students to think more deeply about the importance of space and place in environmental history.

Another aim is to make more use of the Great North Museum: Hancock and its collections including introducing the students to the library and archives of the Natural History Society of Northumbria and some of the museum’s taxidermy collections that are held in store. This will provide the students with a great opportunity to get up close with some historical objects and original primary source material and will hopefully inspire new project ideas. Getting into the museum will also help the students to reflect on some of the issues surrounding its collections and the historic and current role of museums, libraries, and heritage more broadly.

Longer term, I would really like to better enable the students to plot and map some historic data so that they can make full use of what ArcGIS StoryMaps offers. This proved too much of a stretch to do effectively in the module’s first year and may require reworking the first assessment so that it supports that outcome.

Hopefully this blog post may help others thinking about teaching environmental history/humanities and using more creative forms of assessment in their practice. Enrolments for 2022/23 are higher than last year, so fingers crossed the trend continues and global environmental history remains a permanent fixture of our offering in History at Newcastle University.

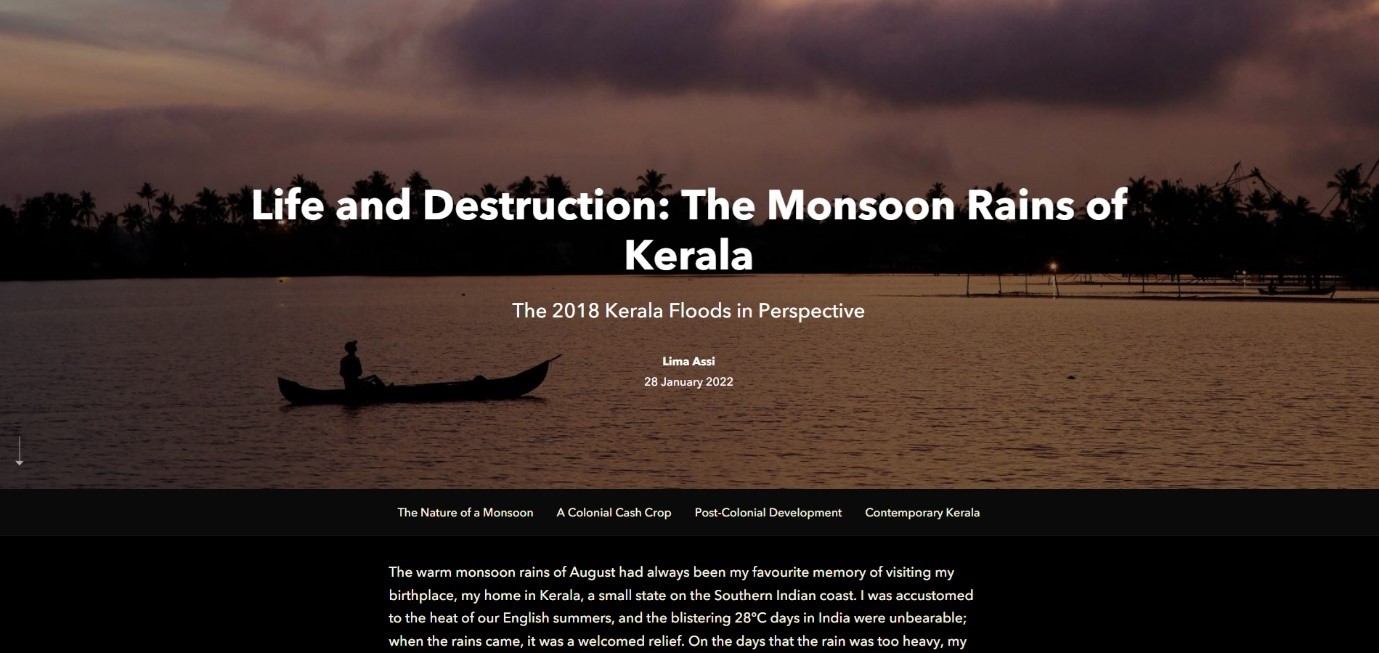

EXAMPLE STORY MAPS

You can find links to some of the Story Maps the students produced below (shared with their permission).

- Life and Destruction: The Monsoon Rains of Kerala

- Imperilled Ecology: The Offensive Against the Ecuadorian Amazon

- Chomolungma to Everest: How Western Imperialism took on the World’s Highest Mountain

- Lessons of the Little Ice Age: For Anthropocene Climate Change

- Skeletons of History: Environmental Vulnerability and Famines in 19th Century China and India

- Yellowstone: A Manmade Wilderness

- The Beavers vs the British: The Fur Trade and its Impacts on the Indigenous Peoples and Beavers of North America

FURTHER RESOURCES

- Andrew C. Isenberg, ed., The Oxford Handbook of Environmental History (Oxford University Press, 2014).

- Karen Jones, ‘Putting the Past in its Place: Teaching Environmental History in the Age of the Anthropocene’, Historical Transactions Blog, 27 Nov. 2020.

- J.R. McNeill and Erin Stewart Mauldin, eds., A Companion to Global Environmental History (John Wiley & Sons, 2012).

- John F. Richards, The Unending Frontier: An Environmental History of the Early Modern World (University of California Press, 2003).

- Christopher Saladin, ‘Story Maps Help Humanities Students Develop Spatial Perspectives’, ESRI Arcuser Newsroom, Fall 2019.

- Emily Wakild and Michelle K. Berry, A Primer for Teaching Environmental History: Ten Design Principles (Duke University Press, 2018).

The Rise and Decline of Newcastle's Public Toilets

How Newcastle went from boasting over 80 public toilets a century ago to zero today.

Using the toilet is a non-negotiable, everyday occurrence for people. Although overlooked by most historians, the provision of toilets can tell us how inequality, sexism, and capitalism structures this essential biological need.

New research from the School of History, Classics and Archaeology in Newcastle University explores this hidden history by looking at the development of public privies and urinals in the late 1800s, as well as the reasons for their dwindling supply and eventual disappearance in the past 20 years.

Working with archival photos of old conveniences, detailed architectural plans, and Ordnance Survey maps of Newcastle city centre’s toilet locations, researchers have created an interactive web page that shows the timeline of Newcastle’s toilets and the “hotspots” for public convenience provision in the past.

The website has been created by Newcastle University student Maud Webster as an environmental humanities project. Working alongside academic Dr Shane McCorristine, Webster was inspired by the difficulties people had in finding public toilets during Newcastle’s Covid lockdowns, as well as the recent repurposing of two former Victorian toilets on Bigg Market and High Bridge into bars.

This blog covers Weird Fiction and our estrangement from natural environments. This is new research from History Undergraduates.

This word - “weird” - can have numerous meanings, stretching from a sense of strangeness and dislocation in certain places, to an awareness of oddity and behaviours or practices that lie outside the realm of the normal. In scholarship and popular culture the weird has been associated strongly with a dark genre of literature and cinema.

Writers and poets have always been interested in eerie moments of strangeness, unexplained disappearances, and the lurking presence of the “old gods” or “ancient ones”. In the late nineteenth century/early twentieth century the genre of weird fiction reached a peak with the stories and novels of British and Irish authors such as Arthur Machen (1863-1947), Algernon Blackwood (1869-1951), and Lord Dunsany (1878-1957). These works typically featured human protagonists who were suddenly targeted by unknown forces that they could not fully comprehend.

In the past few decades the weird has also become associated with cinema - films such as Donnie Darko (dir. Richard Kelly, 2001), The Lighthouse (dir. Robert Eggers, 2019), The Lobster (dir. Yorgos Lanthimos, 2015), and Pan’s Labyrinth (dir. Guillermo del Toro, 2006), tap into the sense of human insignificance in the face of dark forces. Folk horror - a particularly rich sub-genre of the weird - has also featured prominently in supernatural-themed films such as Witchfinder General (dir. Michael Reeves, 1968), The Wicker Man (dir. Robin Hardy, 1973), Midsummar (dir. Ari Aster, 2019), and The Witch (dir. Robert Eggers, 2015).

So what has the weird got to do with the environmental humanities? Well in recent years scholars such as David Punter, William Hughes, Elizabeth Parker, and Sharae Deckard have explored the theme of the “ecoGothic” - that is, the role of climate, place, and the environment in gothic fiction. Woods and forests have long featured in northern European culture as sites of fear and dread - notably they are still key locales for modern horror films like The Blair Witch Project (dir. Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez, 1999) and The Ritual (dir. David Bruckner, 2017). Critics such as Parker have exposed the ecological context of weird forest stories, arguing that despite extensive deforestation and the extinction of species that might attack humans, we continue to tell woodland tales of fear, darkness, and death. Clearly the genre of the weird is something that should interest all students of the environmental humanities.

These topics were discussed in a new Stage 2 undergraduate module in the School of History, Classics and Archaeology entitled HIS2320 - The Supernatural: The Cultural History of Occult Forces. Several students wrote essays on the topic of weird fiction and our estrangement from the natural environment and below are excerpts from two essays by Poppy Foster and Abbie Thorn. They showcase some of the excellent work that was carried out by students on HIS2320 and highlight some of the key environmental questions that weird fiction raises.

Poppy Foster

The Willows

A classic example of weird fiction is the 1907 short story “The Willows” by Algernon Blackwood. The story follows a pair of friends, the narrator and the Swede, as they canoe down the River Danube and make camp on an admittedly unstable island, covered in willows, for the night. Throughout the story the narrator describes feeling something profound which he can’t quite put to words other than a general sense of it being intensely disquieting and unpleasant. After a restless night and experiencing things beyond reasonable explanation, the narrator comes to learn that the pair’s equipment has been damaged, stranding them another day and night. The narrator learns the usually unimaginative Swede also shares an uneasy feeling about the place and shares the narrator’s belief that they are on the borders of some world beyond our own, with beings beyond their comprehension working against them

The narrator learns the usually unimaginative Swede also shares an uneasy feeling about the place and shares the narrator’s belief that they are on the borders of some world beyond our own, with beings beyond their comprehension working against them. The pair is originally joined on the island by strong winds which block most other sounds until they quiet, being replaced by an ominous humming noise which they can only be figure as the sounds of the four-dimensional beings which accompany them. The story ends when upon waking up the next morning the river has soothed, and the humming noise vanished, the cause eventually being found out as a successful ‘sacrifice’ being made in the form of a peasant washed upon their shore, dead, in the night.

Abbie Thorn

The Willows

The idea of wild spaces being untouched by humans is very prominent in Blackwood’s “The Willows”. It is described as a ‘land of desolation’ devoid of ‘any single sign of human habitation and civilization within sight. The sense of remoteness from the world of humankind, the utter isolation’ and the two characters in question go on to laugh, with admiration but also tinged with arrogance and mocking, that ‘we ought by rights to have held some special kind of passport to admit us, and that we had, somewhat audaciously, come without asking leave into a separate little kingdom of wonder and magic—a kingdom that was reserved for the use of others who had a right to it, with everywhere unwritten warnings to trespassers for those who had the imagination to discover them.’

Blackwood had many inspirations for his work which fed into his focus on the theme of humans vs nature. In the biography of Blackwood by Mike Ashley, we read that a lot of his work was inspired by his own life and experiences with nature. Indeed Ashley notes that Blackwood took his own trip along the Danube River, an experience that lived with him and must have grown in the imagining. That the experience came within two years of the events that inspired “The Wendigo”, his other acknowledged masterpiece, shows that by now Blackwood’s spirit was sharply attuned to the majesty of Nature and was storing images and experiences that would soon flow from him in a torrent’.