News & Events

Where do people learn about mental health disorders?

By Felicity Ellis

Mental health literacy is a multi-faceted construct that broadly refers to an individual’s understanding of mental health. Increased levels of the related concept ‘physical health literacy’ have been found to be related to better physical health, but is the same relationship true between knowledge of mental health conditions and wellbeing? Given the increased concern about young people’s mental health in particular, and a greater push to increase levels of mental health literacy with the hope of improving young people’s mental health, it is important to understand where people already learn about mental health and how (or whether) the accuracy of mental health knowledge relates to wellbeing and psychological distress.

Previous research has suggested that the majority of education into mental health occurs within a school setting, but the study reporting this finding mostly involved people on a psychology course so it may not necessarily be representative of where the population as a whole learn about mental health.

Method

The current study recruited both university students and people from the general population. Participants were presented with 6 psychological disorders - Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), Anorexia Nervosa, Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD), Bipolar Disorder, Schizophrenia and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD). If participants indicated that they recognised the name of the disorder, they were asked to identify how confident they were that each of 8 symptoms were features of the disorder (4 were correct and 4 were incorrect). Each symptom was rated from -2 (‘confident it is not a symptom of the disorder’) to +2 (‘confident that it is a symptom of the disorder’), with sum scores created for each disorder. Scores were reversed for the incorrect symptoms, so the total possible score for correctly identifying all 4 symptoms and correctly rejecting the 4 incorrect symptoms was +16. On the flip side, if anyone responded completely incorrectly, the lowest possible score was –16. A ‘total knowledge’ score was created by averaging each individual participant’s scores for the disorders that they responded about.

After answering the knowledge questions for a given disorder, participants were presented with a list of sources of information and asked to indicate where they had learned what they knew about that disorder (they could tick more than one source).

Finally, participants completed a general Psychological Wellbeing scale that focuses on lifetime wellbeing, and the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale that measures current distress.

Results

196 people participated (mean age 25.89; 69% female/26% male/5% self-described). 122 (62%) reported having studied a subject related to mental health in higher education.

Mental Health Knowledge

Schizophrenia and OCD were the most recognised mental health disorders, while MDD and NPD were recognised by the lowest number of participants.

Optimistically, the average knowledge score was 3.61, suggesting people were right more than they were wrong. Schizophrenia was recognised most readily by participants, however they struggled the most with correctly identifying the features of it - average knowledge scores were only 1.74 (joint lowest with Bipolar Disorder). Unfortunately, some common stereotypes were incorrectly identified as features, most notably ‘irritability or aggressiveness’ and ‘behavioural outbursts involving damage of property and/or physical assault involving physical injury against animals or other individuals’.

The mental health condition that had the highest average knowledge score was OCD (6.63) followed by Anorexia Nervosa (6.50). The average scores for MDD and NPD were in the middle (MDD=4.00; NPD=3.63).

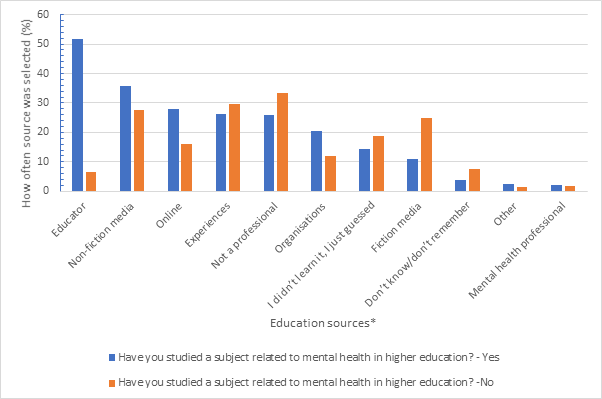

Knowledge scores were associated with some of the demographic variables measured. Those who identified as female usually had better knowledge of the features of mental health disorders compared to those who identified as male. When looking at the effects of age, younger participants typically had higher scores, but this may have been skewed by the high proportion of younger participants who said they had studied a subject related to mental health in higher education, as this was another factor that related to higher knowledge scores (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Average knowledge scores for each disorder according to whether the particiapnt had or had not studied a subject related to mental health in higher education

Source of knowledge

The most common sources of education identified for the 6 mental health disorders differed (see 'Key' below fig. 2 for definitions of categories). ‘Educator’ was the most selected option for schizophrenia and OCD, whereas for MDD and anorexia nervosa it was ‘experiences’. For NPD, it was ‘online’, and for bipolar disorder it was ‘not a professional’ (which incorporated peers, family members and celebrities).

Fig. 2 shows the differences in the importance of the sources of information depending on whether the participant had studied a subject related to mental health in higher education. As participants could select more than one source for each disorder they recognised, the total number of times a source was selected was tallied up for both groups separately, making use of percentages to account for the difference in number of participants in each group.

Fig. 2: The most-commonly identified sources of education about mental health disorders reported by whether participants studied a subject related to mental health in higher education. *Order of categories is based on proportions within the ‘Yes’ group

Fig. 2 Key:

- Educator (includes ‘Educator trained in field related to mental health’ & ‘Educator not trained in field related to mental health’)

- Not a professional (includes ‘Peer (e.g. friend, colleague)’, ‘Family member’ & ‘Celebrity’)

- Experiences (includes ‘Personal experiences’ & ‘Exposure to others with mental health disorders’)

- Organisations (includes ‘Information from a health service (e.g. NHS), such as a website or leaflet’, ‘Mental health charity’ & ‘Mental health service within an educational institution or place of work (e.g. university, occupational health)’)

- Mental health professional (includes ‘Medical practitioner’ & ‘Mental health practitioner’)

- Online (includes ‘Results of an ‘open’ internet search’ & ‘Social media’)

- Non-fiction media (includes ‘Academic/non-fiction book’, ‘Documentary’ & ‘The news’)

- Fiction media (includes ‘Fiction book’ & ‘Fictional TV show/film’)

For those who had not studied a subject related to mental health, the most common source for learning about mental health disorders was ‘not a professional’ (including friends, family and celebrities), followed by ‘experiences’. Interestingly, in both groups, mental health professionals and organisations (such as charities and the NHS) had relatively low rankings. Unsurprisingly, participants who had studied a subject related to mental health in HE selected ‘educator’ much more often than those who had not.

Relationship between knowledge-source and accuracy of disorder-knowledge

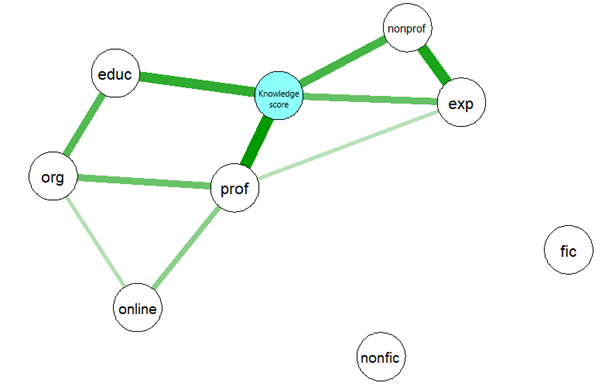

We were interested in whether information source was related to knowledge scores - do some sources of information lead to more accurate knowledge than others? As participants could select more than one source and responded to more than one mental health condition, it was difficult to undertake simple analysis to explore this. We used network analysis with each knowledge source as a node (representing the total number of times an individual had selected that source across all disorders that they recognised), as well as participants’ average knowledge score for all the conditions they answered questions about.

The network is shown in fig. 3. The lines between the nodes in the network indicate the strength (thicker lines are stronger relationships) and direction (green = positive relationship, red = negative) of associations between the nodes when controlling for all the other nodes in the network. Overall, knowledge scores were positively associated with knowledge derived from mental health professionals (node name 'prof'), educators ('educ'), the broad category 'not a professional’ ('nonprof') and ‘experiences’ ('exp'). There was no direct relationship between knowledge scores and learning mental health information from non-fiction or fiction media, organisations or online.

Fig. 3: Sources of education* related to overall knowledge score means

*Key:

‘Educ’ = Educator (includes ‘Educator trained in field related to mental health’ & ‘Educator not trained in field related to mental health’)

‘Nonprof’ = Not a professional (includes ‘Peer (e.g. friend, colleague)’, ‘Family member’ & ‘Celebrity’)

‘Exp’ = Experiences (includes ‘Personal experiences’ & ‘Exposure to others with mental health disorders’)

‘Org’ = Organisations (includes ‘Information from a health service (e.g. NHS), such as a website or leaflet’,

‘Mental health charity’ & ‘Mental health service within an educational institution or place of work (e.g. university, occupational health)’)

‘Prof’ = Mental health professional (includes ‘Medical practitioner’ & ‘Mental health practitioner’)

‘Online’ = Online (includes ‘Results of an ‘open’ internet search’ & ‘Social media’)

‘Nonfic’ = Non-fiction media (includes ‘Academic/non-fiction book’, ‘Documentary’ & ‘The news’)

‘Fic’ = Fiction media (includes ‘Fiction book’ & ‘Fictional TV show/film’)

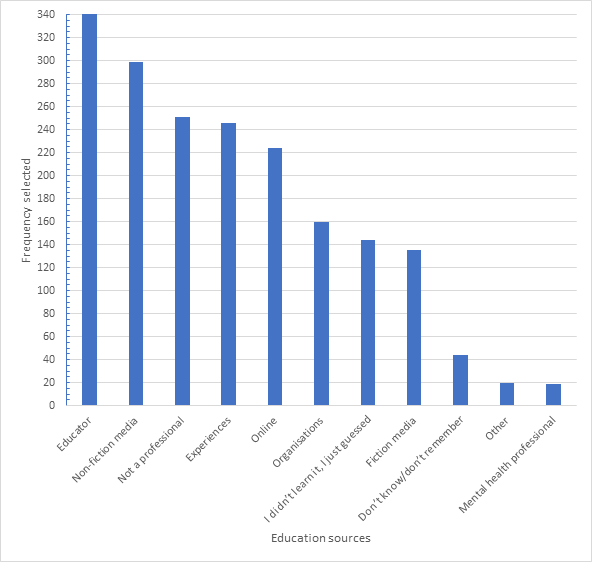

However, these findings are not fully reflective of the frequency each option was actually identified as a source of education about the mental health disorders. ‘Educator’, ‘not a professional’ and ‘experiences’ were all selected often, but ‘mental health professional’ (the option most associated with higher knowledge scores) was actually the least selected option, meaning that only a small number of participants identified it as a source that had taught them about any of the mental health disorders (see Fig. 4). Additionally, ‘non-fiction media’ was the second most selected option, but had no relationship with knowledge scores. This could potentially suggest that the sources of information people are accessing most often about mental health are not associated with greater accuracy in their knowledge about mental health.

Fig. 4: How often different sources were identified as the source for information about the mental health conditions

Relationship between disorder-knowledge and wellbeing

There was a negative relationship between knowledge scores and wellbeing and a positive relationship with psychological distress (indicating that those with better mental health disorder knowledge have lower wellbeing and higher distress). This is an intriguing finding. Although it would take more resesarch to work out the direction of causality, one possiblity is that those with poorer wellbeing/higher psychological distress are more likely to learn more about mental health, either because it is personally relevant to them or in their journey to find help and understanding of their experiences.

Limitations

The measure we used for mental health disorder knowledge had not been used before and we developed it just for this project. More work is needed to understand whether it is a valid and accurate measure. The sample was biased towards people who identify as female, younger people and people who have studied a subject related to mental health. Broader work including a more representatitive sample of the general population is needed.

Conclusion

On the plus side, knowledge about mental health disorders was generally more accurate than not (knowledge scores were positive for all conditions studied), but higher knowledge is not associated with higher wellbeing or lower psychological distress. Some incorrect stereotypes persist in people's understanding of mental health conditions (e.g. that schizophrenia is associated with violence). People identified a range of sources that they learned about mental health and these varied for different disorders. The sources people identified using the most were not the most strongly associated with more accurate knowledge about mental health disorders. Whether improving knowledge of mental health disorders forms part of an effective strategy to improve mental health and wellbeing is an open question, but this study has helped us identify where people most commonly learn about mental health disorders, which would help with where to focus such efforts for maximum effect.

Felicity Ellis (Psychology Undergraduate Placement Year Student 2021-22)

Lucy Robinson

Last modified: Thu, 07 Jul 2022 18:22:06 BST