News & Events

What Do Students Think of Digital Mental Health Interventions?

In an era drunk on the innovations of technology, it is no surprise that conventional mental health treatments such as in-person delivered therapy have also been matched with online equivalents.

Digital mental health interventions (DMHIs) are defined as those that are accessed through an online medium such as an app on your smartphone. These tools are also widely known as e-therapy or e-mental health and can guide you through pre-determined modules/activities that reflect your specific domain of concerns, whether it is learning the principles of CBT to restructure negative thoughts into more constructive ones or using virtual social scenarios to encourage those with agoraphobia to face their fears. Daily monitoring of mood develops the tool’s understanding of the factors that affect your symptoms and provides regular feedback on progress. Such tools can be empowering as they encourage independence by allowing you to take ownership over your own healthcare needs, which can instigate personal reflection and change as well as prevent an over-reliance on a third party, which is often responsible for relapses in traditional therapy.

But perhaps most notably, having a pocket-sized portal to therapeutic treatment at all times, means that unlike the motivation and schedule shifting required to attend in person therapy, DMHIs can be completed at your own leisure, whether that be snuggled up in bed or whilst on the cross trainer at the gym.

The appeal is obvious and with organisations such as NICE (the National Institute for health and Care Excellence) recognizing the clinical benefits to the extent that they’re actually recommending DMHIs for anxiety and depression, many are wondering if digital interventions are the future of mental health. Yet the deciding factor for such a potential revolution firstly requires an understanding of how the target audience actually feels about them.

A questionnaire filled out by 158 students between the ages of 18 and 24 sought to answer this question. Attitude scores from each participant were calculated based on the level of agreement to statements such as “DMHIs improved confidence in managing my own mental wellbeing” and “DMHIs were too impersonal to be used to learn how to improve my mental wellbeing”.

Out of a possible highest score of 65, the average total attitude score from the sample towards DMHI was 44.3, with a score of 3 (indicating neither agreement or disagreement to the statement) being the most common response. This effect remained when the average attitude scores of those who had tried a DMHI before (43.1) were compared to those who had not (44.8). This indicates that whilst the average person who has never tried one doesn’t hold a particular stigma against them, exposure to them doesn’t necessarily increase their value, suggesting DMHIs may not have any quality outstanding enough to shift someone’s attitude away from neutral.

To understand further why this might be, a thematic analysis was conducted on additional free-text comments participants gave in the survey. The most common issue raised was related to the generality of the treatment, with one respondent claiming that participants were “categorised by illness rather than treated on personal grounds”. This lack of tailoring to individual needs strays from the fundamental purpose of a mental health intervention, which is to validate and understand the unique social and biological circumstances of each individual. This lack of specific focus highlights the danger that DMHIs pose by increasing the chance of losing people in a system and treating them as statistics rather than as human beings with varying needs. If the human brain is the most complex thing known to man in the universe, a simple algorithm is unlikely to solve it.

However, user feedback is a priority to developers of DMHIs, who evaluate reviews to make appropriate adjustments and improvements. For example, Silver Cloud, the most commonly used DMHI by the survey respondents, released an initiative to create a more personalised approach based on a branch of artificial intelligence called machine learning. The DMHI giants discovered five heterogeneous subtypes of patient behaviour patterns based on their engagement with the app, which led to the development of more personalised activities. This implies that as technology improves so will the ability to of DMHIs to be subjective and thus any evaluation of them at present is open to change, which is quite an exciting prospect!

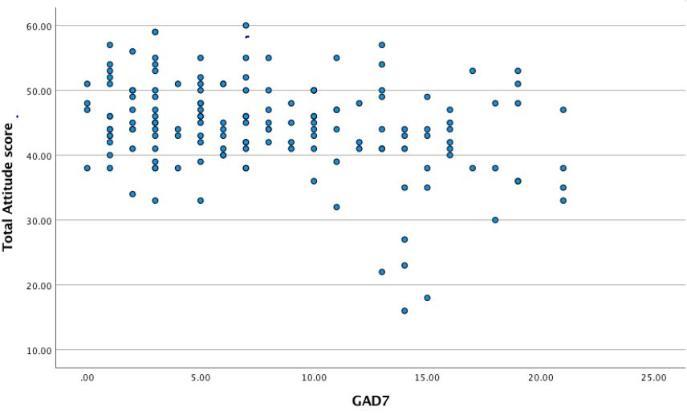

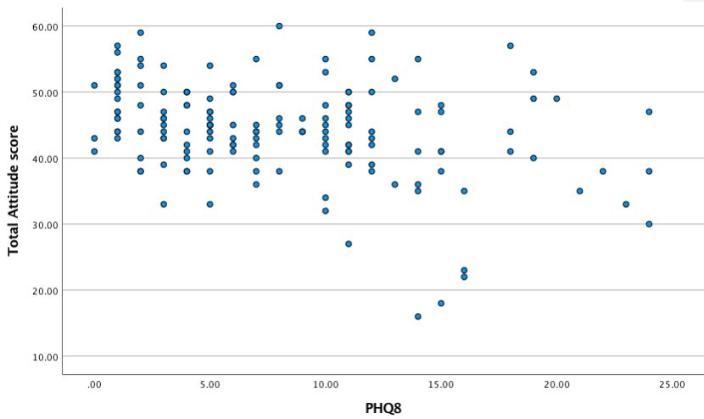

Nevertheless our questionnaire also identified another issue using correlational analysis, which demonstrated a moderate inverse relationship between the current wellbeing of respondents and their attitude score, suggesting that those with an above average GAD7 score (a measure of anxious symptoms) and above average PHQ-8 score (a measure of depressive symptoms), tend to have a lower than average attitude score i.e. a more negative attitude towards DMHIs, as portrayed in the below graphs.

Graph 1: Scatter plot to show the relationship between a subject’s GAD7 score and total attitude score towards DMHIs

Graph 2: Scatter plot to show the relationship between a subject’s PHQ-8 score and total attitude score towards DMHIs

This implies that people with higher symptom levels may not feel that digital platforms are able to deal with all the layers and severity of their problems. As such, DMHIs may be more suitable for those with low to moderate symptoms, a feat that is not all that surprising when we consider how the cause of suffering in many complex clients is sometimes not obvious until many different lines of enquiry have been tried. A robustly-thinking clinician has a higher chance of expending the kind of flexibility required to design the correct formulation that will guide significant self realisations in patients (as well as evaluating body language cues, which are overt communicators of emotion) than the more constrained algorithms of a DMHI. They also are more likely to establish a strong therapeutic alliance with a patient (something that is fundamental in determining improved outcome measures), as empathy from another living human being is more likely to encourage feelings of safety and validation in a patient than words on a screen. As Aristotle says, ‘man is by nature a social animal’, we require human connection to be healthy, something that is of even more importance from a therapist to those so depressed and anxious that they have poor interpersonal relationships.

Another theme extrapolated from the additional comments is caution towards the notion that DMHIs are a good supplementation rather than replacement to live therapy. In this light, DMHIs can be an effective first port of call for those struggling, with one respondent commenting they “would benefit young introverts as a form of pre-therapy”. This captures how daunting the prospect of face-to-face therapy can really be, with bearing all to a stranger being compared to going under the knife without an anaesthetic. Therefore DMHIs may be a way to prime those who are intimidated by traditional therapy, a fear that is also often exacerbated by the catastrophising their anxiety leads to or the lack of energy their depression fosters within them. However the general attitude is that they are no replacement for active alternatives, with the average attitude score towards such a notion being a score of 2 i.e. ‘somewhat disagree’.

Based on the indisputable practical strengths that DMHIs do provide however, present and future directions in mental health will likely be one of blended care. Clinicians may make use of DMHIs as a supplement to the therapy they give directly, whilst national health services may find them a useful tool for those on a waiting list for live therapy to use as a ‘warm-up’ exercise and obtain general tips to improve well-being in the short term.

Manjot Brar, Undergraduate Psychology Student

Anna Shaw, Undergraduate Psychology Student

Lydia Barnes, Undergraduate Psychology Student

photograph credit: John Donoghue

Last modified: Thu, 15 Jul 2021 12:48:26 BST