Film

Writing a political satire for the Elizabethan stage could be a dangerous pursuit, as the case of Thomas Nashe and Ben Jonson’s lost play The Isle of Dogs (1597) makes clear. None of the content of the play has survived, but a Privy Council report describes it as a ‘lewd play…containing very seditious and slanderous matter’. Jonson and the actor Robert Shaa were both imprisoned for two months, though Nashe managed to escape before his rooms were searched by the authorities. He lay low in Great Yarmouth, and dedicated one of his last works (Lenten Stuff, 1599) to the town. It is these events which inspire Brass’ film for the Nashe Project.

Thomas Nashe Lenten Stuff (2019) from Anna Brass on Vimeo.

Anna Brass is an artist and freelance film-maker based in Norwich and London. In 2018 she was awarded the Sainsbury Scholarship in Painting and Sculpture at the British School at Rome. In this interview, she talks with Dr Kate De Rycker (lecturer in Renaissance literature at Newcastle University) about her short film Thomas Nashe’s Lenten Stuff, her love for Great Yarmouth, and getting to grips with this Elizabethan author’s complex prose.

Anna Brass: The film is in two halves, and I wanted them to be opposites and to complement each other. The first half would use an evocative method of storytelling, but one which did not rely on speech because it deals with a period of silence in Nashe’s life: we simply don’t know about the immediate aftermath of The Isle of Dogs, or how he got to Great Yarmouth. Meanwhile, the second half has no characters and only Nashe’s narration from Lenten Stuff. I worked with two musicians (Umi Nowaz and Tom Cagnoni) rather than one because I wanted the different sections of the film to have different feelings, and to mimic things that Nashe does in his writing.

Kate De Rycker: How did you get started with a film project about an Elizabethan writer that you’d not encountered before?

AB: I read Charles Nicholl’s biography of Nashe, A Cup of News (1984) which made me want to include the section from Lenten Stuff and to put Nashe’s trip to Great Yarmouth in context. Usually, though, my films are image led. I do research into contemporary paintings and illustrations, and then this is entwined with a process of making a lot of my own drawings, costumes, and sculptures. Some of the things that I made during this exploratory process ended up in this film, like the dog masks.

I was watching Kozintsev’s Russian Hamlet (1964) and noticed that the play-within-a-play used costumes which were all simplified. It reminded me of some of Maurice Sendak’s drawings which render costumes down to an almost emblematic simplicity. I tried doing that for the Isle of Dogs sequences: the buttons are bigger and the colours are bold.

KDR: I loved the effect of the white face-paint and the red slash of a mouth of one of the actors in that sequence. It was disturbing and poetic, a bit like a visual representation of the way Elizabethan sonnets render beauty down to ‘the white and the red’.

AB: And I remember that, though I didn’t tell you, you correctly identified that that character in white was meant to be Elizabeth I, based on the Marcus Gheeraerts portrait [at the National portrait gallery]. My hula-hoop was sacrificed to make that costume!

The only professional actor in the film is Jimmy [Tucker]. I hired the shoes, I hired some hats, and a pair of trousers, but everything else is made out of remnants that I found in charity shops: duvet covers, blankets, curtains. It’s very DIY.

KDR: Having an actor portraying Elizabeth, snapping back when provoked, also suggests the idea that the original play was offensive to the authorities, maybe even to the queen herself.

AB: I wanted there to be this sense of threat, this edge to it. That character is played by my friend Will Black, who is an artist. That is Will, he wasn’t acting. He was brilliant.

KDR: Elizabeth is often portrayed, but we only have one woodcut image of Nashe. How did you build a visual sense of him as a writer?

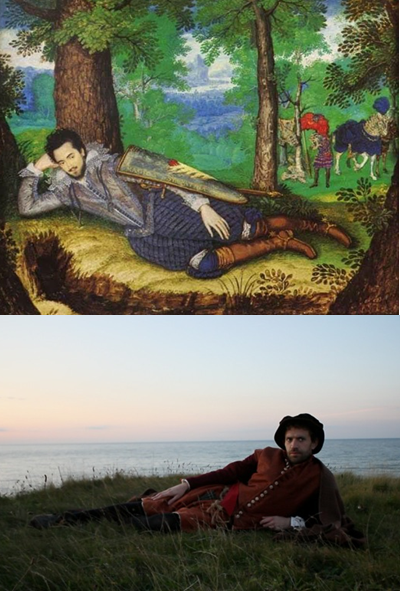

AB: Often, when I start a film, I start with a painting. I don’t really chose it, it suggests itself and in this case it was a portrait miniature by Isaac Oliver of Lord Edward Herbert [currently held by the National Trust].

What drew me to it was the fact that he’s looking directly at you, and I thought there was a correlation with the way that Thomas Nashe talks to his audience. That very direct gaze out of the film was my starting point.

KDR: Yes, it’s a confident pose which suggests someone who’s relaxed with the gaze of the viewer, which captures what’s unusual about Nashe’s writing, and Lenten Stuff especially. Nashe starts his story with an explanation for why he’s in Great Yarmouth, building elements of his notoriety into the narrative.

Usually the opportunity for the author to address their reader directly is kept to the paratext, like the ‘letter to the reader’ that acts as a preface to Lenten Stuff. However, Nashe blurs this line between himself as an author and himself as a character in the wake of The Isle of Dogs mayhem in the opening lines of the main text.

In his prefatory ‘letter to the reader’ Nashe draws attention to the labour that goes into making a book by ending his letter saying that he’s been called away to correct some errors in the press. The black and white section of your film mimics that scene by focusing on the actor, James Tucker (whose voice we hear later as “Nashe”) in a recording studio, with Jennifer Richards and Andrew Hadfield [the two leads on the Nashe Project] and the producer Nick Baker giving instruction and suggestions off camera. It mirrors that sense of the work that actually goes on behind the scenes.

AB: I wanted to lull the audience into thinking it was a documentary by starting in a recording studio. But then it twists into something else, and then twists again. I was thinking a lot about the rhythms in Nashe, and what it meant when he was talking to the reader, and how he was controlling the flow of reader concentration. He can be abrupt, and pull back and then loop around to show you what he’s done. I try to do that in my own work, and so there were lots of things that I was trying to do when filming that resonated with Nashe’s methods, but also with my own interest in looking into different layers of reality, and using some of deliberate anachronisms.

I also wanted to find a way to play with that relationship to the viewer of this film, in the same way that Nashe does with his readers. So in the recording studio, I was filming one actor, James Tucker, doing a voice-over, saying: “I am taking on the role of Thomas Nashe” and he is, but the image that we see of Nashe is another actor, Tazelaar Stevenson. I wanted to use that contradiction, and to end that opening section with him saying “Goodbye” just as the film begins. It felt like a good way to explore the way Nashe constructs the beginning of Lenten Stuff, and to begin in a confusing but also playful way. At the end of the film, I’ve included my own drawings and my notes, and a lot of them where the sketches and notes that I made at the beginning of my process: I like the idea of ending a film with notes from the beginning.

-320x320.png)

KDR: Like you, Nashe likes to draw attention to the artificiality of his work, but it’s also a wider concern of that early modern period. For example, dramatists were experimenting with inset plays as metadramatic commentary on the action of the main play.

AB: I remember speaking to Jenny [Richards] about the first half of the film and she said "ah, like a dumb show". I had never thought about it in those terms before, but when I went home and read more, it seemed to fit what I wanted to convey exactly.

As an audience, seeing a play-within-a-play makes you acknowledge that the thing you're watching is artificial, without puncturing the wider illusion, something which is exciting to think about, the layers of artifice.

I have this thing about authenticity anyway, because I make all these costumes, and I put a lot of time and effort into them. But there comes a point when I think "hmm, I don't like the feeling that I'm trying to get all of this historically spot-on. I have to acknowledge the thing I'm making is new, that I'm not trying to pretend that it is really the 1590s.

KDR:Yes, I suspect it’s a problem for anyone in the culture sector wanting to make something new out of historical material. I’m thinking about somewhere like Shakespeare’s reconstructed Globe on Bankside; part of the reason people visit is because they want to have an immersive experience of what it was like in Elizabethan London, and yet the Globe also embraces historical anachronism by putting on performances of modern plays alongside their usual Shakespeare fare. You can use reconstruction to explore how a certain performance space functions now, but we’re not going to pretend that what an audience is seeing is anything like an original performance. As you say, it’s easy to get swept up in the process, but I agree that anachronisms can be fruitful, so that the join between old and new is visible, a bit like a conservator restoring an old painting.

AB: And Nashe does that, he says “this is a pamphlet”. Jenny [Richards] told me about how Nashe incorporates the sounds of the print-house into the work, and that it draws attention to the fact that this story sits within a material object. I wanted this film to say “this is a film”.

KDR:There are also some really surreal moments in this film. Before the false ‘documentary’ style opening, we hear an eerie hunting song being performed by some of the actors.

AB: The Nashe Project invited me to the ‘Read Not Dead’ performance of Terrors of the Night at the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse, and also to the performance of Summer’s Last Will & Testament by Edward’s Boys in the Old Palace in Croydon, and both had a profound impact on my ideas for the film, especially Edward’s Boys. I was struck by the way music was integrated into their performance, and made it come alive.

My assistant director Tom works in musical theatre, and teaches singing, so when I decided to include a song in the film I asked if he could teach my cast. The two of us looked through Summer’s Last Will and we compiled ideas for a song from the lines about dogs in that play, working out how they could fit together and be made into verses. Then Tom went away and did some research into the music of the period, and he came back with different ideas for melodies, which he taught to my friends who appear as a chorus.

-320x320.png)

KDR: In conversations you’ve had with me, Jenny [Richards], and Andrew [Hadfield], you’ve mentioned how overwhelming your initial experience of reading Lenten Stuff was.

AB: Although I found that the way Nashe writes is very visual and in fact very sculptural, the first time I read it, I couldn’t envisage any kind of structure for the film, so that took quite a long time to work out. But that initial encounter with his writing, which is so rich and bewildering, left a deep impression on me and I wanted the finished film to leave the audience with a similar feeling. I tried not to shy away from that overwhelming, overflowing energy and rhythm of Nashe’s writing, and wanted that discombobulation to be folded into the film somehow.

KDR: I think one of the difficulties with Nashe is that his writing is really circuitous and works by association; he leaps from one thought to another which gives the impression of being extemporal, but which you eventually suspect is carefully crafted. The second part of your film seems to replicate that experience of associative imagery really well through the layering of voice and images.

AB: The idea for the second half of the film was locked down from early on in my process. I wanted to look for evidence of the Great Yarmouth that Nashe speaks about, and to make a double image of Great Yarmouth, though the way to do it came a bit later than that initial concept. Nashe conjures up an image of a prosperous Elizabethan city, and how underneath that ‘modern’ city lies another Great Yarmouth. He describes how this important city came to be. I wanted to look at the Great Yarmouth that Nashe experienced, and the one I experienced when I went looking for the things he mentioned; it’s about trying to find these layers that make up a city, looking for the lost city of Great Yarmouth.

My feelings changed about Great Yarmouth over the course of the year that I was working on the film. A bit like Nashe’s experience, I started in one place and ended up somewhere else. The first time I visited it was three days after the Brexit referendum. I live in Norwich [which voted to remain in the EU] which is about thirty minutes ride to Great Yarmouth, and when I got off the train it was clear why Great Yarmouth voted to leave. Like many seaside towns it’s been neglected, it needs money.

Over the year that I went back to Great Yarmouth, I’d go to art events organised by Kaavous Clayton and Julia Devonshire called Original Projects.Their art organisation, gallery and the events they were running engage with the local community, so whilst I started out thinking that Great Yarmouth was quite a sad place, the more I went the more I realised how fantastic it is. It’s wonderful! There’s so much happening, it’s so beautiful, the buildings are so interesting; it needs some money, definitely, but I realised that this place was amazing.

KDR: It sounds like you were slowly growing in love with Great Yarmouth over that year.

AB: Yes! I now feel like I’m in a similar position to Nashe, because I can talk at length about why I love Great Yarmouth! I felt like I had a developing relationship with that town, and I hope that comes across in the film. And I decided that I didn’t want to focus on the idea of a sad seaside town, because Great Yarmouth is so much more complex than that.

KDR: That decision comes across in the second half of your film, especially when we hear Nashe’s description of this as an idealised town where the wealth is shared out fairly, overlaying your photographs from the modern and early modern town. Even though sharing of wealth is something that’s certainly not happening today on a national level, it conveys a hope in a city and its citizens. Your layering of voice and images brings out that mixture of emotions, rather than trying to say that this is a sad case of a neglected town.

AB: Absolutely, and I think a lot of what Nashe says is still pertinent to contemporary Great Yarmouth: it’s still got a relevance as a town, and what rings true is, for example, his talking about its relationship with its near neighbour, Norwich.

KDR: So was this an innovation, this layering of photographs? Because you said that early on you wanted to draw out the historical Great Yarmouth and have it sit alongside the modern town. How did you come to this idea of conveying those overlapping histories?

AB: I went on some research trips to Great Yarmouth and took my digital camera, hoping to capture the interesting architectural structure of the city. I was trying to relate the twenty-first century town to what I saw in an old map of Great Yarmouth that was made in the 1540s, and is now held in the British Library.

But then when I got home and would look at these photographs of the city on my laptop, it was just boring: the digital images were just too flat, too high definition. They were just some pictures of some buildings and didn’t capture the excitement of looking. I have a 35mm camera, which used to belong to my grandfather, and I love using it because it conveys texture in a way that digital never does, plus it records natural light in a really thrilling way. I’d wanted to use my 35mm photographs in my films for quite a while, but I wasn’t sure how. It occurred to me one day that I could collage the 35mm photograph over the digital footage, and that this might set up a tension between the images.

That double image is the conceptual heart of the second half of the film, so you get this experience where you’re trying really hard to look at both images at once, but one is trapped behind, so you feel frustration that you can’t see it properly. The images on top are almost like heavy objects which sit on the screen. The effect is that you are being shown two images which are both different from each other, but which resonate. So you could make this really lovely rhythm with the interplay between these two images, and then sequences of images, and I thought that would be a really rich way to convey the rhythm of Nashe’s text. I didn’t want to illustrate what he was saying, so I thought it would be more of a visual accompaniment, suggestive of how he writes, rather than simply illustrating its content.

There are moments when the images and the words ‘touch’ at the same point, but they’re quite carefully mapped out, so it’s only occasionally that they do that. So you’ll see an image and then after the image, you’ll hear James [Tucker] talk about what you just saw; they only touch each other quite sparsely. It also allowed for instances of humour to be brought out, moment that I didn’t want to be too obvious, but which are there in the scenes from modern Yarmouth.

KDR: I especially love the ending, with Nashe transplanted into modern day Yarmouth, at a disco and on the snail ride in his Elizabethan costume!

AB: Taz [Stevenson] is an amazing dancer, at the first costume fitting I went down to his studio and he put a record on and started dancing – I wanted to include that. Those final scenes included the character of the Elizabethan clown Will Kempe too, because my friend Alida sent me a picture of a plaque in Norwich that commemorated Will Kempe’s dance from London to Norwich. I like to fold chance encounters into my films, so I asked her to play Will Kempe. And after I did that, you told me that it was likely that Nashe and Kempe would have known each other. This film ends partly in Norwich, and partly in this club in Great Yarmouth!

Originally, when I had the film planned out, I wanted it to end quite abruptly with Nashe’s death at the end, and the prone figure in the landscape was going to be in a shroud. But half way through, I changed my mind. I’d had such a good time making the film that I wanted it to have a more joyful ending.

KDR: I think that’s a great place to end our interview too! Thanks so much for talking to me about your film.