An Un-Common Waste

An Un-Common Waste

One of the important questions that the ‘Past’ aspect of the Wastes and Strays Project is considering is the role of commons in relation to their specific urban contexts. What were these spaces used for, by whom, and with what authority? Several functions spring to mind – many of which will be explored further within these blogposts – but, there are also unexpected uses that resonate with contemporary debates on misuse of landscape and environmental impact. To facilitate these discussions it is worth recounting one such unconventional use of the Town Moor in Newcastle upon Tyne that challenges our notions of what urban commons were used for in the past.

At approximately 4pm on the 17th of December 1867 Newcastle’s buildings shook as a loud explosion was heard throughout the city and along the banks of the River Tyne. The origin of the explosion was difficult to ascertain – some suspected a locomotive had exploded, whilst for others it heightened fears of an attack from the Irish Republican group, the Fenian Brotherhood.

The true cause was rooted in the disposal of a rather un-common waste on the Town Moor.

On the morning of the 17th, Newcastle’s police were alerted to the existence of nine canisters of nitro-glycerine being stored within the cellar of the White Horse Inn on Cloth Market (marked by the red star on Reid’s map of Newcastle, 1863).

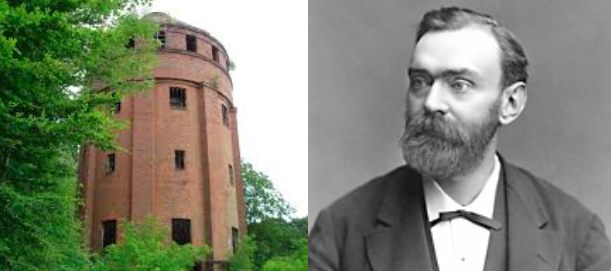

*The Krummel factory in Hamburg (left), where Alfred Nobel (right) & Company experimented to find safe solutions for the use of nitro-glycerine. The canisters found in Newcastle came from the Krummel factory.[i]

The Corporation took swift action. Newcastle’s town clerk, Mr Philipson, advised police that unless the nitro-glycerine was taken out of town and destroyed within the hour, the owner would be liable to penalties and prosecution. As a precaution Mr John Mawson, a chemist and Sheriff of Newcastle, and Mr Thomas Bryson, the Town Surveyor, were tasked with assisting the police officers. Mawson and Bryson settled on a spot on the Town Moor where historic coal extraction had already caused subsidence.

The nitro-glycerine was taken through the city by cart. In total nine people were present on the Moor to assist or watch the disposal of the nitro-glycerine: Mawson and Bryson; Thomas Appleby (the cartman); James Shotton (a local labourer); Constable Donald Bain and Sub-Inspector Mr Wallace; Stanley Waddley and James Stonehouse (fourteen year old bystanders who followed the cart out of curiosity); and a further unnamed adult male.

Shovels were used to shear off the ends of the canisters and the liquid nitro-glycerine was poured onto the Moor, but the cold weather had caused crystallisation within the canisters.[ii] Ever the chemist, Mawson broke off a piece of the crystal and put it into his pocket for later inspection. The decision was then taken to dispose of the remaining crystallised nitro-glycerine a few yards away within a secondary area of subsidence. Sub-Inspector Wallace was left at the first site to cover up the liquid nitro-glycerine with soil.

Moments later, there was a terrible explosion at the second site.

Wallace’s life was saved due to a small hill that screened the first site from the blast occurring at the second site. He described scattered fragments of clothing and human remains falling around him, including his friend’s foot! A similar account was produced by Dr Walpole who had been taking a walk on the Moor and was about three hundred yards away when the explosion occurred. Of the original party, Wallace was the only survivor. Furthermore, the list of fatalities included by-standers, one of whom was never identified and two of young age. Nor were all the deaths immediate – a 14 year-old boy survived for a further hour before dying, and Mawson and Bryson clung to life until the following day. This highlights both an alarming lack of attention to safety by Mawson and Bryson and also contests the anticipated emptiness of the Town Moor by the authorities – they saw no danger in spreading chemicals on the Moor because it was perceived as vacant.

The events were shocking, but even during their grief there was also some relief for Newcastle’s inhabitants. The following day the Newcastle Daily Journal expressed an opinion that was likely shared by some, “while deploring the great extent of the calamity that has befallen us, we may well be thankful that it is no worse, and that the centre of Newcastle, with its valuable buildings and extensive commercial transactions and busy population, has not been reduced to a heap of ruins”.[iii] As it turned out it was indeed fortunate – it was only after the explosion that the authorities realised that thirty canisters had been stored in the cellar for at least six months without detection.[iv] The Newcastle Daily Journal calculated that this quantity of nitro-glycerine had the equivalent explosive power of more than two and a half tons of gunpowder – furthermore the rear of the White Horse Inn was close to the Bank of England building on Grey Street!

There appears to have been little regard for the impact that the events had on the Moor as a landscape. The Pall Mall Gazette summarised the problem presented to the Corporation succinctly. The nitro-glycerine “was not in a proper place, and the magistrates ordered its destruction. It was taken to the Town Moor, a large open space, and emptied on the soil”.[v] The choice of words here is important because it was, and still can be, reflective of attitudes towards commons as open spaces of lesser economic benefit. It is interesting that of the choices presented to them, including emptying the nitro-glycerine into the River Tyne, disposal on the Moor was considered the least damaging option.[vi] In other words, the city depended on the river as an economic resource, but the Moor was not viewed in this way. It was a place within Newcastle but disconnected from the built environment of the city, and its use was sporadic rather than constant. Furthermore, it was an opinion that was shared – in the weeks that followed police enquiries within the north east led to the discovery of other stocks of nitro-glycerine including a canister found near to Chester-le-Street that was taken onto Waldridge Fell and detonated, producing a five-by-six foot crater in the peat.[vii]

Town Moor, Newcastle, July 2019 © Sarah Collins

Lesser known histories can facilitate discussion between urban commons and human experience. Our project is concerned with understanding these commons as a valued space within the daily lives of the urban inhabitants who lived in proximity to them, rather than an isolated geographic location. Unconventional practices on the common - some that were far removed from original rights and customs - reflect attitudes that counter this notion: commons could be treated as a space of ‘otherness’, somewhere that was expendable in comparison to the built environment of the city. To a contemporary audience the events on Newcastle’s Town Moor are striking as we have better understanding of the health and wellbeing benefits of green spaces. In Newcastle, events such as World Cleanup Day have been used by non-profit organisations such as the Skill Mill to litter-pick after events such as the Hoppings, whilst providing employment opportunities for young people. But, our urban green spaces are still under-threat and it has been encouraging to uncover the amazing work of volunteers fighting to protect them from future damage like that considered here.

Dr Sarah Collins, Newcastle University

December 2019

[i] Birgitta Lemmel, ‘Alfred Nobel in Krümmel’, created February 1998 by The Nobel Prize, https://www.nobelprize.org/alfred-nobel/alfred-nobel-in-krummel/

[ii] The Newcastle Daily Journal, December 21, 1867, accessed May 17, 2019, Issue 3717. British Library Newspapers, Part III: 1741-1950

[iii] The Newcastle Daily Journal, December 18, 1867, accessed May 17, 2019, Issue 3714. British Library Newspapers, Part III: 1741-1950

[iv] Ibid.

[v] The Pall Mall Gazette, December 18, 1867, accessed May 17, 2019, Issue 891. British Library Newspapers, Part I: 1800-1900

[vi] Mawson feared that the nitro-glycerine would be washed about in the River and cause damage. Alternative suggestions included removing it from Newcastle by rail, but the Clerk of the railway refused after learning of the compounds destructive properties. See, The Newcastle Daily Journal, December 18, 1867, accessed May 17, 2019, Issue 3714. British Library Newspapers, Part III: 1741-1950

[vii] The Newcastle Daily Journal, December 30, 1867, accessed May 17, 2019, Issue 3723. British Library Newspapers, Part III: 1741-1950