Kett's Rebellion 1549

Kett's Rebellion, 1549

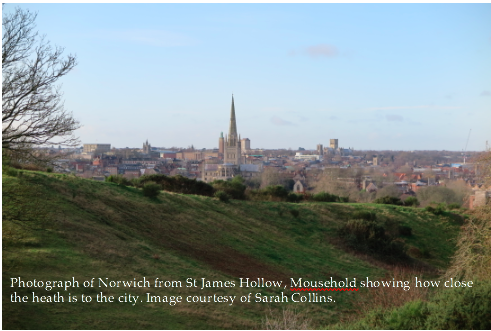

On 10 July 1549 - 471 years ago this month - Robert Kett, along with his brother William and a crowd of supporters from the surrounding rural area, arrived in the city of Norwich, teamed up with poor inhabitants of the city, and began destroying enclosures that had been erected on the city commons. Having settled on Mousehold Heath, just outside the city, they drew up a series of demands. In a previous blogpost we explored the appeals to historic rights over common land on Mousehold Heath by nineteenth-century residents of Norfolk. Mousehold Heath, then, was the focus of conflict concerning common rights and land over several centuries.

As well as constituting one moment in a longer chronological history of resistance by commoners in and around the city of Norwich, Kett's Rebellion was also one episode in a wider uprising in 1548-9 known as the 'commotion time'. While there were other issues at stake (not least attempts by the government to firmly establish Protestantism) an important spark for these uprisings was the anti-enclosure proclamations issued in June 1548 and April 1549. Enclosure - the parcelling out of common land into individual privately owned plots - was an affront to common rights. This was often viewed as a rural issue and many of the uprisings of 1548-9 were rural in focus. One distinctive feature of the Norfolk case was the urban setting and the solidarity between urban and rural protesters who travelled from all over Norfolk and Suffolk to join the rebellion. A deeper investigation of the case helps to explain this solidarity and why Mousehold Heath was chosen as the location for the rebel camp.

It was the launch of a second enclosure commission on 8 July 1549 that was the immediate spark for the uprising in East Anglia. During traditional celebrations associated with the dissolved abbey in the rural Norfolk town of Wymondham, crowds marched into surrounding fields to dismantle hedges and fences. Some of these fences were on land belonging to Robert Kett a local yeoman farmer. Rather than objecting to the destruction of his property, Kett agreed with the rioters that the enclosures should be removed and offered to lead them 'in defense of their common libertie' (Holinshead Chronicles as quoted in Andy Wood, Riot, Rebellion and Popular Politics in Early Modern England. Palgrave, 2001, p. 63). The rebels marched ten miles towards the city of Norwich, destroying other enclosures along the way.

While the city authorities refused the rebels entry, the poor people of Norwich were quick to make common cause with their rural neighbours, having recently been engaged in conflicts over the enclosure of common land within the city. In choosing Mousehold Heath as the location for their camp, the rebels were further alluding to these issues. Mousehold was itself a vast tract of common land (originally stretching all the way from the city to the coast), which was increasingly subject to enclosure. The very act of occupying that land was a symbolic enactment of the common rights being demanded. In addition, Mousehold had also been the site of a rebel encampment 60 years previously at the time of the Peasants' Revolt, further strengthening its symbolic significance.

Kett and his supporters arrived at Mousehold Heath on 12 July and immediately set up camp. Over the next month they engaged in negotiations with the national government, which led to the drawing up of a list of demands. While similar demands were issued from various rebel camps, only those from Mousehold survive in full. In line with the broader aims of the movement, the Mousehold articles begin by calling for an end to the enclosure of common land. Reclaiming the rights of commoners from the gentry and clergy and preventing communal resources from being exploited to the point of depletion were also key concerns. As well as rights to common land, the demands also referred to common rights to the waterways, insisting that rivers should be 'ffre and comon to all men for fyshying and passage'. Yet perhaps the most striking aspect of the Mousehold demands is the emphasis on the right to common. This was the focus of the third article, which read: 'We pray your grace that no lord of no mannor shall comon uppon the Comons.' The implication of this was that the rights of the commons were to be reserved for the commoners alone, not the nobility and gentry. The point was reiterated in article 11. 'We pray that all freholders and copieholders may take the profightes of all comons, and ther to comon, and the lordes not to comon nor take profightes of the same.' ('Kett's demands being in rebellion', 1549, reprinted in Anthony Fletcher and Diarmaid MacCulloch, Tudor Rebellions, 5th edition, London & New York, Routledge, 2014, pp. 156-9).

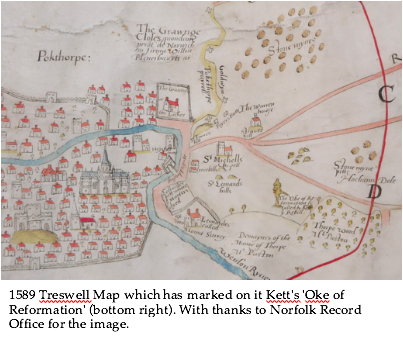

Moreover, as well as asserting their right 'to common' at the expense of local landowners, the rebels also adopted communal - even proto-democratic - practices. Despite the numbers involved being in the thousands - possibly as many as 16-20,000 - the camp was carefully organised. Justice was administered by Kett and his councillors from the 'Oak of Reformation' located in Thorpe Wood at the southern edge of the Heath. On their orders a number of gentlemen were imprisoned at Surrey Place, the former residence of the Earl of Surrey who had recently been executed. A representative council was also established comprising spokesmen from each of the Norfolk and Suffolk hundreds participating in the rebellion. It was this council that issued the Mousehold demands (suggesting that they were the outcome of a consultative process). It also issued warrants to gather food, cattle, weapons, and people on Mousehold Heath to allow the camp to function.

On 21 July a royal herald arrived at Mousehold Heath. Some rebels accepted the general pardon that he offered, but Robert Kett refused on the grounds that he and his supporters had broken no laws. The herald then declared him a traitor. Kett and his followers stormed the city of Norwich the following day and took control, forcing the mayor to put his name to their demands. The rebels defeated the Earl of Northampton's army sent to crush them and held out for a month. It was only following the arrival of reinforcement troops on 23 August, under the leadership of the Earl of Warwick, that they were eventually defeated. Even then it took four days of skirmishes, resulting in the deaths of an estimated 2-3,500 protestors. Kett was captured and he and his brother were sent to London to stand trial at the King's Bench. They returned to Norfolk for their execution. William was hanged from the tower of Wymondham Abbey and Robert on the wall of Norwich Castle.

The historian Andy Wood has argued that the brutality of the closing stages of the Norfolk uprising (which was out of line with those that took place elsewhere) was largely due to the rebels' distrust of the pardons that were offered to them, and that this reflected deeper divisions within Norfolk society. There were long-standing tensions between the commons and the gentry, but such tensions were also as much a feature of urban as rural areas, meaning that the poor of Norwich and the commoners of rural Norfolk sympathised with each other and were willing to make common cause at a time of crisis. (Andy Wood, 'Kett's Rebellion', Medieval Norwich. London: Hambledon, pp. 277-300).

Kett's Rebellion, then, reveals a number of interesting points about conflict over common rights and the relationship between the substance and method of protest that was employed. While in other areas the 'commotion time' of 1548-9 was a predominantly rural affair, the specific circumstances of Norfolk and the recent history of conflict in both the city and rural community - as well as the important presence of urban commons both within the city walls and just outside - brought together urban and rural rebels in pursuit of a common cause. The conflict was essentially a simple, but fundamental, one between the poor and the rich. At issue was not merely the ownership of land, but the exercise of rights. In their choice of location for their camp and in their actions, Kett's supporters were able to make manifest the connection between urban and rural demands and could simultaneously voice and enact their right to 'comon uppon the Comons'.

Dr Rachel Hammersley, June 2020