Hidden Histories: Town Moor

Hidden Histories: Town Moor

As the oral historian attached to the Wastes and Strays project, I have been struck by the ways in which the histories of our case studies are often invisible to the hundreds of people who walk, run and cycle across them daily. This doesn’t mean that they are forgotten, rather that there is little by way of historical infrastructure or physical remains to hint at some of the monumental events that have taken place on our common land. As the researcher on the ‘present’ strand of the project, I am most interested in the ways in which the history of the case studies interacts with the present, and most importantly, preserving the voices and memories of the people who use it now. Our repository of oral history interviews will provide a new primary resource, which could inform academic research, policy change or local interest. In this series of blog posts I look at each of the case studies in turn, to explore this idea of invisible history, and how generations of people have understood and interacted with this land.

Newcastle Town Moor

Newcastle Town Moor is open grazing land adjacent to the city centre, surrounded by the city on all sides. Despite some large-scale building work on the edges of the land, the Moor has remained a large space, with little alteration to the main plot. Where land has been given for building, for example to extend the stadium or the hospital, land is assigned in kind. This means that the Moor is divided by roads and there are some pockets of land adjacent to the main stretch. In this case, the geography of the Moor alludes to the history of the space. The Newcastle Chronicle referred to the Town Moor as one of Newcastle’s great survivors, and it is clear why.[1] Perhaps more than any of our other case studies, the history of the Moor is bound up in its survival. Where a space like Mousehold Heath in Norwich is infused with its history in a way that influences folklore over the centuries and inspires common memory, the Town Moor has carried its history forward, into the present. The rights of the Freemen to graze cattle ensure that the land cannot be developed or built upon, but unlike Clifton Downs in Bristol, these rights are not simply ceremonial, and the invisible history of the Town Moor is symbolised by the cows that graze there from April to October every year. Dr Rachel Hammersley argued that ‘a sense of historical right to a place, of this is how it is and has been since time immemorial, can be incredibly powerful … different periods of time have left layers of history in Newcastle, and the Town Moor is part of that.”[2]

Cows on the Moor (Photo: Chronicle Live)

The Town Moor has been protected by an Act of Parliament since 1774. The Act secured the Freemen’s grazing rights and there has long been a feeling of public “ownership” of the Moor. How the Town Moor is managed today is set out by the Newcastle upon Tyne Town Moor Act 1988, which updated the 1774 Act. A joint committee of the Freemen and the city council decides on the management under the terms of the 1988 Act, which says that the Moor should be maintained as an area of open space in the interests of the inhabitants of the city. Professor Christopher Rodgers has argued that these statutes are responsible for the protection that has maintained the space and access to it for centuries:

The Town Moor has survived because it has been protected by statute since 1774, updated in 1988, which sets out the responsibilities of the Freemen and the city council … The Town Moor is different in that it is a green lung right in the middle of a built-up area. A lot of local authorities are having to sell green space to raise money, but we are very lucky that our jewel in the crown is protected by an Act of Parliament, which guarantees public rights.[3]

The endurance of the Freemen and the preservation of the Town Moor are directly interlinked, and the cows that graze there have become something of a symbol of the centuries of memories residents of Newcastle associate with their open space. Indeed, a common theme of the oral histories I have collected so far is the pride in the Moor, and the recognition that it makes Newcastle different.

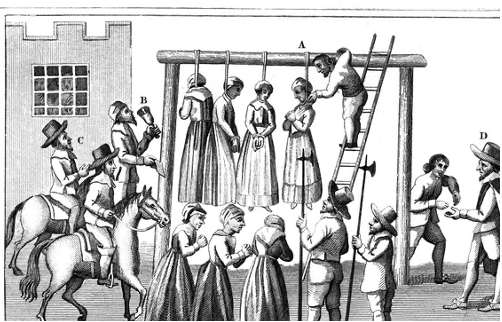

Aside from the history of the Freemen and the cattle, the space has other invisible histories that have left little physical trace. One macabre example, as depicted in this graphic illustration, was the murder of fifteen ‘witches’ in 1650. These executions took place on the Moor.

An illustration of the fifteen 'witches' being hanged on the Town Moor, 1650. Courtesy of Newcastle Libraries (Image: Newcastle Chronicle)

According to writer Ralph Gardiner, in 1655 two Newcastle Magistrates sent men to Scotland to bring back a notorious witch-finder, promising him twenty shillings for every witch he identified.[4] The magistrates sent their ‘bell-finder’ through the streets of Newcastle, who proclaimed that ‘all people that would bring in any complaint against any woman for a Witch, they should be sent for and tryed by the person appointed.’ After pricking all the accused with pins, to see if they bled, fourteen women and one man were imprisoned and executed on the Town Moor.[5] Later, the witch-finder himself was ‘cast into prison, indicted, arraigned and condemned’ and executed, but only after enabling the execution of two hundred and twenty women.[6] There is no monument or memorial to this on the Moor, and the picture above appears to be one of the few physical representations of this history. But standing on the Moor, especially during one of its more isolated periods of the day, this dark aspect of its history seems more believable.

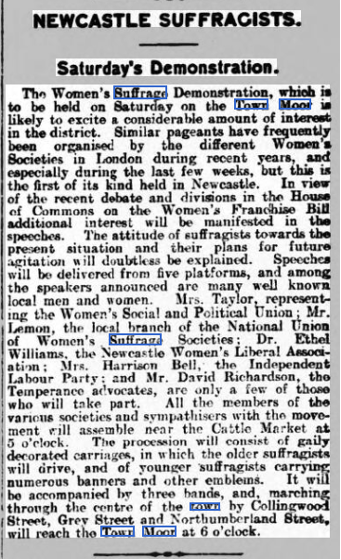

The open spaces in our case study, particularly Mousehold and the Town Moor, seem to inspire political gatherings and revolutionary discourse, perhaps because they symbolised the commonality of the working classes, because they were large enough to contain the masses who attended, or even because the open air offered a safer place to congregate than the enclosed spaces in the city centre. In June 1910, Newcastle Suffragettes met on the Moor after processing through the town in ‘gaily decorated carriages.’ In June 1938, 70,000 people attended a meeting of the chartists to hear speeches on the rights of working-class men from Feargus O’Connor. The crowds spilled out beyond the boundaries of the Moor, and Northern Star called the meeting ‘the most splendid display of the working classes ever witnessed in England.’[7]

Newspaper article describing the intended suffrage procession (Newcastle Evening Chronicle, Friday 15 July 1910)

The environmental history of the Moor is another fascinating aspect of our research. In our interviews, some extolled the importance of a giant green lung in the centre of the city, others discussed ‘the green desert’, a monoculture that had the potential to offer much more to combat climate change and air pollution. This presented an interesting question: despite the history of the space, do we need to adapt in light of the threat to our environment, and how do we do it?

Interestingly, the history of bird watching offers insight into the environmental changes of the Town Moor over the last two hundred years. Records in the Hancock’s archives record species spotted (and often, unfortunately, shot) on the Moor. A list compiled in 1889, by a Mr R. Duncan, begins as follows:

The following is a list of birds I have either shot or observed on the Town Moor of Newcastle during a period extending over the last thirty-five years … The Town Moor is an open grassy space, comprising about 1,000 acres, bounding the town on the north and west. Formerly, before it was so extensively drained, there were numerous sedgy pools of water, which remained all the year round, and the outskirts consisted of fine hawthorn hedges and tall trees.[8] These latter and the pools are nearly all gone, and in consequence many birds which used annually to resort here, now rarely come or have altogether disappeared … Although close to a large town, many very rare specimens are recorded. Shooting was formerly permitted on the moor, but has been stopped for some years past.[9]

Duncan comments on the frequency of the birds, and made notes on habitat that are quite revealing when trying to consider the environmental history of the Moor. Common Sandpiper, usually spotted in May, had ‘disappeared since the ponds were drained.’ The Skylark, ‘common twenty-eight years ago’ fell victim to lark-nets and the drainage of the moor; ‘the birds have nearly all left.’ Goldfinches, spotted thirty-five years prior to Duncan’s list, disappeared along with the nurseries that had previously adjoined the Moor. By contrast, Duncan noted that the Magpie had ‘totally disappeared’, the last nest on the border of the Moor in 1853. If you walk the Moor now, Magpies will be one of the few birds you will certainly see. Newcastle residents made their concerns known through the Letters pages of the local newspapers.

-

Letters (Newcastle Evening Chronicle - Friday 22 May 1970)

-

Letters (Newcastle Evening Chronicle, Wednesday 12 March 1980)

As with Mousehold, it’s fascinating to consider this invisible history of gatherings, political upheaval and change, tied to place but without the physicality of a museum or any infrastructure to preserve it. We still host mass events on the moor, including the Hoppings, the Mela and the Pride festival. Despite the invisible nature of the Moor’s history, there are many ways in which these stories can be rekindled and recognised, and we can consider these options as part of the project. Audio tours, self-guided walking tours, or podcasts can provide a story to accompany a space, whilst also encouraging visitors and footfall to these important locations.

Dr Olivia Dee

December 2020

[1] Tony Henderson, “The Varied Life of Newcastle’s Town Moor, and why it remains protected.” Newcastle Chronicle, 12 June 2019.

[2] Tony Henderson, “The Varied Life of Newcastle’s Town Moor, and why it remains protected.” Newcastle Chronicle, 12 June 2019.

[3] Tony Henderson, “The Varied Life of Newcastle’s Town Moor, and why it remains protected.” Newcastle Chronicle, 12 June 2019.

[4] Ralph Gardiner, Englands grievance discovered, in relation to the coal-trade with the map of the river of Tine, and situation of the town and corporation of Newcastle : the tyrannical oppression of those magistrates, their charters and grants, the several tryals, depositions, and judgements obtained against them : with a breviate of several statutes proving repugnant to their actings: with proposals for reducing the excessive rates of coals for the future, and the rise of their grants, appearing in this book. (London: R. Ibbitson and P. Stent, 1655).

[5] Ibid

[6] Ibid

[7] Northern Star, 30 June 1838, p.4.

[8] Sedgy refers to an area covered with sedges. Sedges are grass-like plants, associated primarily with wetlands or marshes.

[9] R. Duncan, “The Birds of Newcastle Town Moor” July 1889. Hancock Museum, Newcastle, p. 213