Hidden Histories: Mousehold Heath

Hidden Histories: Mousehold Heath

As the oral historian attached to the Wastes and Strays project, I have been struck by the ways in which the histories of our case studies are often invisible to the hundreds of people who walk, run and cycle across them daily. This doesn’t mean that they are forgotten, rather that there is little by way of historical infrastructure or physical remains to hint at some of the monumental events that have taken place on our common land. As the researcher on the ‘present’ strand of the project, I am most interested in the ways in which the history of the case studies can interact with the present, and most importantly, preserving the voices and memories of the people who use it now. This repository of oral history interviews will provide a new primary resource, which could inform future academic research, policy change or local interest.

In this series of blogposts I look at each of the case studies in turn, to explore this idea of invisible history, and how generations of people have understood and interacted with this land.

Mousehold Heath

Mousehold Heath has been used by the people of Norwich for over 1000 years. It has been, in recent years, the focus of a concerted effort to maintain it as a protected, open space. A series of management plans, the most recent of which covers 2019-2028, were created by the Mousehold Heath Conservators and the city council to ‘… to enhance the biodiversity of the site through the restoration of nationally declining habitats, building on the important work around increasing understanding of the heath through volunteering opportunities and educational programmes as well as ensuring the site offers a safe and welcoming environment for all its visitors.’[i] The Heath is designated as both a Local Nature Reserve and a County Wildlife Site.

As with so many of these spaces, there is a complex history of ownerships over the centuries, but its current status is defined in the management plan:

Mousehold Heath was given to Norwich City Council (then known as the local corporation) in 1880 by the church to look after on behalf of the citizens of Norwich. The City of Norwich Mousehold Heath Scheme Confirmation Act was passed by Parliament in 1884. The Mousehold Heath Conservators were constituted following the passing of the act to maintain and preserve Mousehold Heath.[ii]

For a historian, Mousehold is fascinating, as so much of its history is invisible or reduced to remains that only hint at the stories and local legends that have arisen over the centuries. Oral history can play an interesting part in rekindling and exploring these hidden histories, as local knowledge and memories interact; playing in the old chapel nestled in the woods on the heath and sledging down the man-man hills on the Town Moor.

Mousehold was supposedly the location of a violent and ritualistic murder. In 1144, twelve-year-old William of Norwich, now a saint and martyr, was killed and left in the woods.

St Agatha Holding Pincers and a Breast; St William of Norwich with Three Nails in His Head (panel from a rood screen), Norwich, 1450-1470, artist unknown. Victoria and Albert Museum.

A chapel was built on the site of the murder but later destroyed, likely during the Reformation. The land is managed to make the land forms and other features of the chapel visible, and blogs of local historians and writers make it clear that this history has endured:

"Within it, Long Valley in particular makes one feel that Norwich is far away and that the only exciting thing that would happen below the deciduous canopy of Mousehold is for Robert Kett to emerge with the city’s authorities in hot pursuit. The wood’s deciduous canopy also does more than cushion objects of our imagination, it muffles the noise of vehicles on those roads that run circles round the area, including that odd little field or two set amongst the trees. It is a wood veined with sand and flint edged pathways that have been cut through ridges by centuries of feet; nice pathways, many of them through birches growing in shallow areas either side. Pick the right one, but avoiding bramble, rough undergrowth, burrs and ticks and the site of a largely forgotten chapel will emerge; here the mind can get lost in time for that place is where the ‘St William’s Chapel in the Wood’ once stood."[iii]

© Copyright Evelyn Simak, from Geograph.org.uk/photo/2062003

The story of William and his chapel has been depicted in art across Great Britain. According to the Mousehold Defenders, paintings of the martyr are located in Norfolk, Kent and Suffolk, yet the site itself is largely invisible, unless you know exactly what you are looking for. In the 12th century, a new chapel was dedicated to St. William, the murdered boy. The Chapel of St-William-in-the-Wood was, according to historian E.M. Rose, likely destroyed during the reformation but ‘substantial: the walls were reputed to have been more than two and a half feet thick. Today it is marked only by some stones at the edge of a soccer field, the overgrown site protected by the Ancient Monuments Act, first enacted by Parliament in 1882.’[iv] Is a story, so imbued with violence and enduring fear, worthy of increased physical demarcation?

In an 1835 edition of the Norwich Magazine, an essay entitled “Tales of Mousehold Heath” discussed in further detail the enduring effect of the story of the William in the Wood, 700 years later. In this extract, two gentlemen are exploring the location of the long-destroyed chapel, and attempting to map the ruins in detail:

… we were on the point of abandoning the farther investigation, when we saw approaching towards us, a labourer, bearing on his shoulder the tools with which he had been at work in a neighbouring gravel pit. Wishing to avail ourselves of such opportune assistance, we hailed the countryman, when to our great surprise, without regarding our signals, he turned off abruptly from the path which crossed the monastery grounds … it was evident that he avoided us and the strangeness of his conduct induced us to follow him … When he found that we were advancing towards him, he first quickened his pace; but as soon as we had cleared the bank of earth … he stopped, as if awaiting our approach. As we drew near, we heard him exclaim, in a tone half arguing with himself, and half addressed to us, “Why sure, and they be proper gentlefolks after all!”

“Did you take us then for robbers or ghosts?” was our immediate enquiry?

“Nay, your honors,” replied he, “a poor man ha’ no need to be afeard o’robbers; and as for ghosts ….”[v]

When the men asked about their frustrated attempts to map the land, the labourer comments on how those from the city don’t understand the power of the history of the land, and the menacing presence of those from the past:

‘T is astounding but to hear how light you city gentry can make o’ such matters … in all the sixty long years that I have lived hereabouts, nevers the time that I have ventured across Pockthorpe Churchyard after nightfall. And as for grubbing the old walls, now that the sun’s adown, younger and stouter hearts than mine might flinch from the parlous encounter.[vi]

The labourer went on to say that although he had not seen the ghosts himself, there was a common knowledge about the space, and he knew of many who had. He also described the frequent unnerving occurrences that he attributed to the spirits of the Heath:

In every gust o’ wind such moans and yells, such shrieking, howling, and roaring ha’ burst upon our ears that we ha’ been struck dumb wi’ terror; and sometimes, when the burly ha’ been at its height, my half-burn pipe ha’ dropped from my lips, just for all the world as if one o’ the wicked urchins had crept in and dashed it on the hearth; and my dame’s spinning-wheel ha’ stopped all on a sudden stock still, like as if the goblin had laid upon it a hundred pounds weight or more.[vii]

This story, with its likely hyperbole or emphasis, is wonderfully evocative of the communal stories and myths that surround these spaces we are researching, especially in certain, historically significant locations. This essay, part of a series, demonstrated how our understanding of common land can often come through people’s experiences of the space, in addition to archival and archaeological histories. These collective memories are a common occurrence in oral histories, and this project is no different.

There is also significant invisible history in relation to Mousehold’s use as a political stage, as the Heath was a camp ground for significant challenges to the political status quo. Mousehold was a site of rebellion after a process of land enclosure made it difficult for local peasants to benefit from the land. Despite brief success in seizing Norwich, leader Robert Kett was captured, with 3000 men killed. Kett was hung at Norwich Castle in 1549.

Samuel Wale, Robert Kett, under the Oak of Reformation at his Great Camp on Mousehold Heath, Norwich, 1549, c.1746.

Historian Geoffrey Moorhouse argued that the peasants were angry at a number of laws which threatened their way of life: “local enclosures [were] a particular target of peasant anger, but by no means the only one. People were also aggrieved by rack-renting, by the rise in food prices, by a steady erosion of tenant rights.’[viii] It is interesting to look at some of the demands put forward by the rebels.

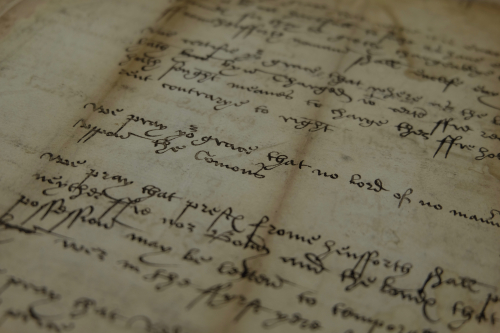

British library: Harley MS 304, f. 75v.

https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2016/11/ketts-demands-being-in-rebellion-1549.html

There are several demands that relate specifically to the importance of common land for the people of Norwich and, more broadly, to all those who relied on public land to survive. This included:

- We pray your grace that no lord of no mannor shall comon uppon the Comons.[ix]

- We pray that Rede ground and medowe grounde may be at suche price as they wer in the first yere of kyng henry the vijth[x]

- We pray that all ffreholders and copieholders may take the profightes of all comons and ther

lordesto comon and the lordes not to comon nor take profightes of the same.[xi] - We pray

that copieyour grace to take all libertie of lete into your owne handes wherby all men may quyetly enioye ther comons with all profightes.[xii] - We pray that Ryvers may be ffre and comon to all men for ffysshyng and passage.[xiii]

- We pray that the pore mariners or ffyssheremen may haue the hole profightes of ther ffysshynges

in this realmeas purpres grampes whalles or eny grett ffysshe so it be not preiudiciall to your grace.[xiv] - We pray that it be not lawfull to the lordes of eny mannor to purchase londes frely and to lett them out ageyn by copie of court roll to ther gret advaunchement and to the vndoyng of your pore subiectes.[xv]

These demands place such emphasis on the dependence so many placed on the lands where they could forage for food, fire wood and their livelihoods, and how they felt that this land, in a sense, belonged to them, and not the wealthier members of society, who were beginning to encroach on this space. Acts of Enclosure and other limitations on common spaces were a serious threat to the well-being of the poorest members of this society. In my oral histories with currents users of these spaces, there is obviously less concern about food and foraging rights, but there is still a fervent belief in the rights of citizens to use these lands for exercise, recreation, health and wellbeing. Just because the nature of use has changed, attachment and dependence on the land has endured.

Aside from these two examples of invisible history, it is clear that Mousehold has inspired creative responses in art and literature for centuries. Art historian Sam Smiles, in his article Mousehold Heath as a Location, has commented on the absence of infrastructure, of subject matter in artistic depictions of the Heath, but also that this itself comments on the power of nothingness. Smiles pointed to Samuel and Richard Redgraves, art writers, who reflected that the barren nature of John Crome’s painting of Mousehold Heath demonstrated ‘how very little subject has to do in producing a fine picture’, arguing that the work was interesting ‘from its painter-like treatment, certainly not from [its] subject.’[xvi]

John Crome, “View on Mousehold Heath, near Norwich”, c. 1812. Victoria and Albert Museum

These open spaces do present similar issues for artists as they do for historians. The absence of features but the presence of vast political and social memory and history mean that, as Smiles observed, Mousehold Heath ‘may be regarded as a landscape whose past whose past was bound up in its present.[xvii] Although painting a picture of MH as more of a blasted heath than the biodiverse, fiercely protect land that we see in modern documents, it is clear that there was something in this space that was worth capturing, and that perhaps this absence of infrastructure was a form of muse. Indeed, art historians Trevor Fawcett and Sam Smiles summarised the importance of local spaces and local art to local people, arguing that ‘the Redgraves’ lofty dismissal of its subject as irrelevant would not have been shared in Norwich … Crome’s treatment of the location in Mousehold Heath, Norwich was deliberately anachronistic, presenting the landscape as though enclosure had not taken place, precisely to re-engage with a landscape lost to modernity.’[xviii]

There is a clear belief in the power of common land for the people of Norwich, whether that be for food and livelihoods in the medieval and early modern period, or in more recent years. In the Mousehold Heath management plan 2019-2028, the Mousehold Heath conservators said that ‘in sharp contrast to [its] outward economic prosperity, Norwich has a low wage economy and high levels of deprivation.’ They continue:

Although important for its wildlife and history, it is much more than a museum or a nature reserve. It is a space that is highly valued as a place where people can enjoy a feeling of being in the countryside whilst still being in the city. It is a place where people can walk, play sport, learn about nature and history, attend an event, or just unwind from the pace of city life.

For many Mousehold is a crucial part of the city, heathland, insect friendly, wildflowers beds with over 40 species, a wide range of birds, mammals and amphibians, bioverse because of a carefully co-ordinated set of monitoring schemes, but still imbued with an almost invisible history, of crucial importance to the citizens of Norwich. As the oral historian on this project, it will be useful to consider firstly how current users understand the history of these spaces, and whether local knowledge has endured, and secondly, whether there are ways of bringing out the history, without the addition of any permanent infrastructure that would impact on the space itself.

Dr Olivia Dee

[i] Mousehold Heath Conservators, “Mousehold Heath Management Plan 2019-2020” Norwich City Council 2019, p. i.

[ii] Mousehold Heath Conservators, “Mousehold Heath Management Plan 2019-2020” Norwich City Council 2019, p.6.

[iii] Norfolk Tales Myths, “William in the Wood” 6th May 2018. https://norfolktalesmyths.com/2018/05/06/william-in-the-wood/

[iv] EM. Rose, The Murder of William of Norwich: The Origins of the Blood Libel in Medieval Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015) p.44.

[v] Anonymous, “Tales of Mousehold Heath” The Norwich Magazine (Norwich: Josiah Fletcher, 1835), p. 151.

[vi] Anonymous, “Tales of Mousehold Heath” The Norwich Magazine (Norwich: Josiah Fletcher, 1835), p. 151.

[vii] Anonymous, “Tales of Mousehold Heath” The Norwich Magazine (Norwich: Josiah Fletcher, 1835), p. 152.

[viii] Geoffrey Moorhouse, The Pilgrimage of Grace: The Rebellion that Shook King Henry VIII’s Throne (London: Orion Books, 2002), p. 366.

[ix] ix-xv are extracts taken from Andrew Dunning, “Kett’s Demands Being in Rebellion.’ British Library Medieval Manuscripts Blog,16 November 2016. https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2016/11/ketts-demands-being-in-rebellion-1549.html Translation: We pray your grace that no lord of no manor shall common upon the common.

[x] We pray that reed ground and meadow ground may be at such price as they were in the first year of King Henry VII.

[xii] We pray that all freeholders and copyholders may take the profits of all commons, and there to common, and the lords not to common nor take profits of the same.

[xiii] We pray that Rivers may be free and common to all men for fishing and passage.

[xiv] We pray that the poor mariners or fishermen may have the whole profits of their fishings as porpoises, grampuses, whales, or any great fish so it be not prejudicial to your grace.

[xv] We pray that it be not lawful to the lords of any manor to purchase lands freely and to let them out again by copy of court roll to their great advancement, and to the undoing of your poor subjects.

[xvi] Sam Smiles, “Mousehold Heath as a Location’, in Sam Smiles (ed.), In Focus: Mousehold Heath, Norwich c. 1818-20 by John Crome, Tate Research Publication, 2016. https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/in-focus/mousehold-heath-norwich-john-crome/mousehold-heath-location

[xvii] Sam Smiles, “Mousehold Heath as a Location’, in Sam Smiles (ed.), In Focus: Mousehold Heath, Norwich c. 1818-20 by John Crome, Tate Research Publication, 2016. https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/in-focus/mousehold-heath-norwich-john-crome/mousehold-heath-location

[xviii] Trevor Fawcett, ‘John Crome and the Idea of Mousehold’, Transactions of the Norfolk and Norwich Archaeological Society, vol.38, part 2, 1982, pp.168–81 in Sam Smiles, “Mousehold Heath as a Location’, in Sam Smiles (ed.), In Focus: Mousehold Heath, Norwich c. 1818-20 by John Crome, Tate Research Publication, 2016. https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/in-focus/mousehold-heath-norwich-john-crome/mousehold-heath-location