Common Celebrations

Common Celebrations

Social isolation has quickly become a way of life. Over the last two months, local residents have used urban commons for daily exercise within household groups giving an isolated feel to these green spaces. Historically, commons could also be places of extreme isolation. Such isolation occurred, in part, because of the location of green spaces relative to the population that used them. Clifton Down, Mousehold Heath, and the Town Moor are all good examples of urban commons where the built environment did not encroach the green space until the later nineteenth century. In addition, isolation was also present for those who led secluded lives, such as the incumbent of the lone Shepherd’s Hut on Mousehold Heath. However, urban commons were also spaces of communal gathering and merriment. At a time when many of us are creating new ways to celebrate with each other via a screen, or eagerly awaiting the embrace of loved ones, it seems appropriate to consider these more positive aspects of past human behaviour within our urban commons. This month’s blogpost is a celebration then of three such gatherings that occurred on the urban commons, we are studying in the past.

Royalty on the Steine and Level:

Brighton has a history of culinary festivities in association with Royal visits and the Steine and Level provided suitable space to accommodate these events. J. A. Erredge[i], writing in 1867, recorded three of these events:

- On 19 July 1821, crowds gathered on the Level to celebrate the coronation of George IV. The Corporation had two bollocks roasted whole, which were served out to the crowd to mark the occasion;

- On 3 September 1830, a commemorative dinner was held on the Steine to commemorate William IV and Queen Adelaide;

- On 4 October 1837, Brighton officials hosted a banquet on the Steine when Queen Victoria visited the city for the first time.

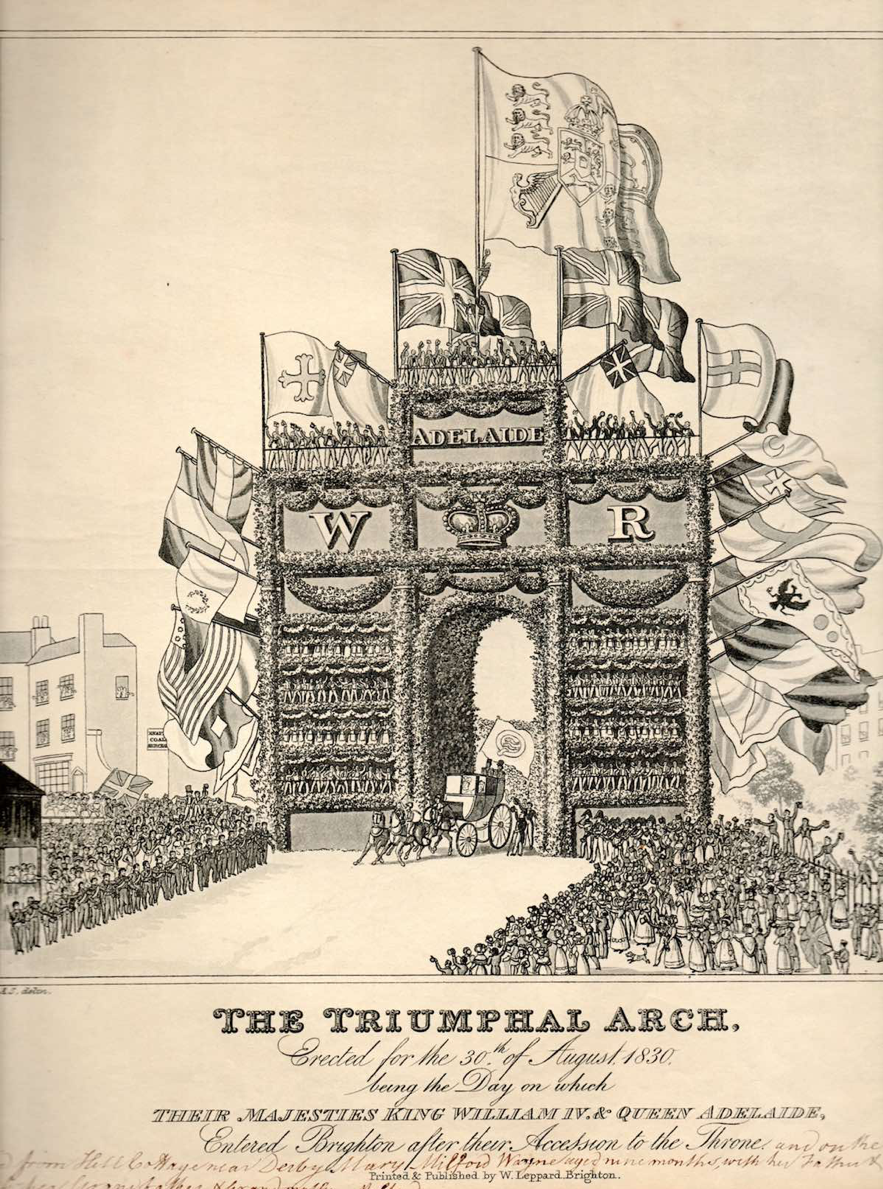

The celebrations to mark William IV and Queen Adelaide’s first visit to Brighton were one of the most elaborate the town had experienced. The Morning Post detailed the excited preparations for their arrival on 30 August.[ii] Particularly impressive was the erection of the Triumphal Arch at the southern end of Marlborough Place, adjacent to the North Steine and just north of the Royal Pavilion.[iii]

The Triumphal Arch, Erected for the 30th of August 1830 © Society of Brighton Print Collectors

Reports vary, but there can be no question that the finished structure was impressive. The arch was approximately thirty to fifty-feet high and made up of separate compartments that were similar to boxes and galleries at the theatre, and then ornamented with foliage and hundreds of flowers, as well as flags and banners.[iv] Within the structure tiers of men, women and children waved to the Royal carriage and at the summit of the arch were sailors and officers from the Hyperion Frigate, three of which can be seen in the above image starting to scale the central flagpole. The following report from the Morning Post captures the fanfare of the day,

‘In the midst of the rattle on cannon, and the shouts of the populace, and the waving of handkerchiefs, their Royal Highnesses reached the Pavilion, the jolly tars on the summit of the splendid bridge uniting their huzzas in the common cause’.[v]

The celebrations continued into the night with the triumphal arch illuminated by 4000 lamps, and the houses along Pavilion Parade (to the east of the Steine) decorated with further illuminations. Then at 10pm, fireworks were let off on the Steine.

The celebratory events caused huge excitement and crowds – the Morning Post recorded that 60,000 visitors[vi] had been in attendance whether as spectators crowded behind the railings that encircled the Steine, or watching from the balconies of the surrounding buildings to catch a glimpse of the spectacle. The final celebratory gesture took place on 3 September, when town officials organized a great feast. At the southern extremity of the Steine, a marquee accommodated the King and Queen, and children from local charity schools were invited to dine on ‘an unlimited quantity of roast and boiled beef and plum pudding’ at tables and benches in front of the Royals.[vii]

A celebration of the agricultural on Clifton and Durdham Down:

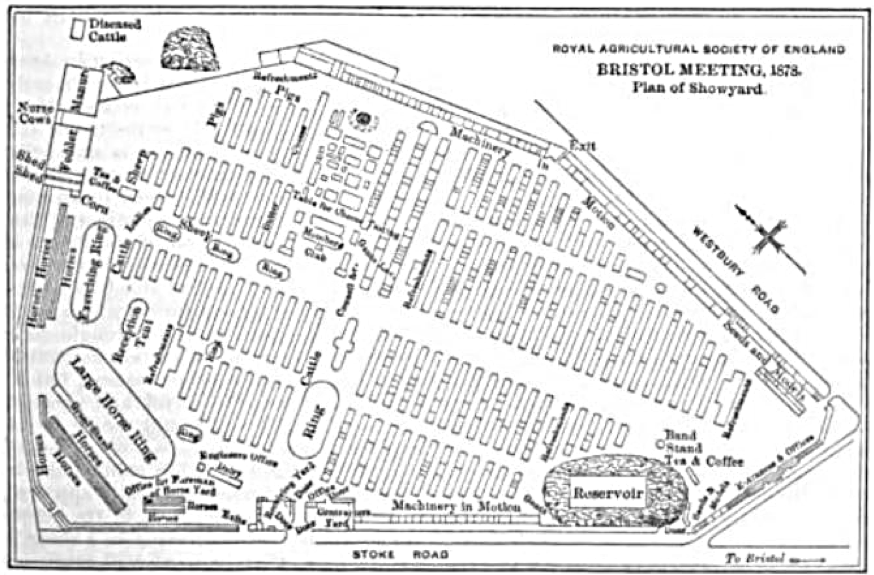

Culinary revelry also occurred on Bristol's urban common Clifton Down during the nineteenth century, but here it was associated with one of the oldest surviving agricultural shows in England. In 1853, the Royal Bath and West Committee (founded 1777) proposed that the show move from place to place to exhibit a different town within the region each year. Clifton and Durdham Down hosted the event at least five times during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, and with each exhibition, the event grew in size. The first exhibition (1864) saw the enclosure of twenty-five acres of the Downs and 545 entries of livestock for the events. By 1903, the exhibition was so sizeable that forty acres were required. Events included exhibitions of poultry, livestock and machinery, practical instructions on skills such as bee keeping, a working-dairy, which instructed on how to make clotted cream, and performances from musicians.[viii]

An American visiting the show in 1878 observed how little it compared to American agricultural shows. Besides the animal enclosures and latest innovations, he found the most interesting feature to be the people – he saw farmers’ wives and house-servants in dresses that had little to distinguish them from their superiors, although in their speech he could detect ‘the lower and richer intonation of educated persons’.[ix] More enlightening for him was the enormous amount of drinking - ‘men and women – of many classes, too – crowding about the numerous large booths where beer and spirits were sold…such beverages would drive an American crowd beyond the limits of decency, and quite beyond the control of the police; here it had no more effect than water’.[x]

Plan of the Clifton and Durdham Down Agricultural Show, 1878

*reproduced in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Vol. LVIII, Dec 1878 to May 1879 (Source: https://books.google.co.uk)

Like the Royal Visit in Brighton, members of the Royal Family visited each agricultural show. Attendance by George V in 1913 was a great honour for Bristol, which is why the appearance of a Suffragette during the open-topped carriage procession proved particularly distressing to the committee. In an act that is reminiscent of Emily Davison’s sacrifice only a month before, Mary Richardson of the Women’s Political and Social Union (Clifton), darted from the pavement and dropped a scroll of paper promoting the suffragist cause on to the knees of the King. She was swiftly taken into police custody but not before the crowd mobbed her – one spectator slapped her and another hit her over the head with their umbrella.[xi]

Temperance Fair on the Town Moor:

In stark contrast with the merriment of drinking on Clifton Down was Newcastle upon Tyne’s first Temperance Fair on the Town Moor. The three-day festival opened on the 28 June 1882. The first fair was a positive response to a visit by the temperance lecturer R. T. Booth in 1881. Temperance organisations wished to build on his success and the fair provided a suitable venue to champion the cause. In addition, officials favoured the scheme because it helped to retain the midsummer holiday, which they feared would lapse because the Town Moor race meetings relocated to Gosforth after the 1881 season.[xii] The event, which attracted 150,000 people, was organised by Newcastle’s Freemen, Councillors and various Temperance societies. The Newcastle Courant wrote, ‘townspeople and persons from neighbouring towns and villages attended in much larger numbers than we have ever known assemble on the Moor before’.[xiii]

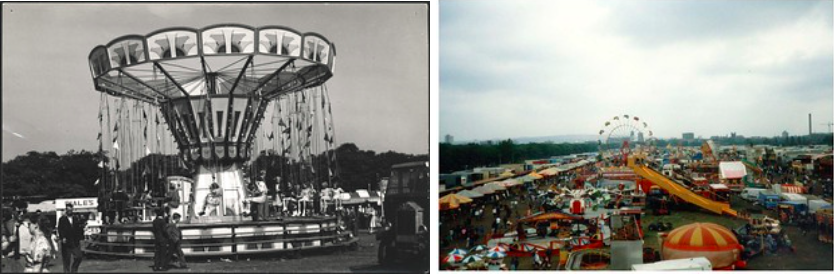

The fair was a deliberate departure from vice that some felt accompanied the Town Moor race meetings – the prohibition of alcohol was a notable success, but so too was the ban of cardsharps or other incitements to gamble.[xiv] Instead, those in attendance enjoyed brass-band contests, bicycle races, football and cricket matches, children’s sports and games such as hurdle races and tug-of-war, as well as fairground rides and acrobatic displays. The event was a mixed social occasion with benefactors’ deliberately showing benevolence to the local poor children though treats such as oranges and buns, and prizes such as hats and shoes.

The Hoppings has been providing a welcome and vibrant sight to the Moor throughout its multiple iterations. By the 1890s, visitors welcomed the steam-driven roundabouts from show-families such as the Murphy’s and Hoadley’s, and in the early 1900s, the ‘helter-skelter’ was introduced for the first time.[xv] The success of that first fair established an annual tradition that is a northeast institution, and although the rides are much faster today the spirit of family oriented fun remains by combining the traditional and modern.

(right) Swing Ride, 1940; (left) View of the Hoppings, 1990 © Tyne & Wear Archives and Museums

Comparatively these examples share some common themes despite temporal differences. Firstly, they reveal the important association between food and drink within festival settings – whether through its consumption or deliberate rejection. Moreover, although the amount of alcohol consumed at the agricultural show was surprising to the American visitor his reflections were not intended as chastisement, but rather acknowledged the sociability that drinking together encouraged. The emphasis on socialisation, entertainment and participation was an important driving force at these celebratory events. The joyous nature of these occasions was a possible contributing factor in the crowd's negativity towards Mary Richardson in the moments that followed her protest – people were unwilling to compromise celebration for such a political act. Such emphasis on participation was also present in acts of benevolence – the contributions of local benefactors in Brighton and Newcastle meant that children not only participated, but also experienced special treatment. Such acts were valuable to those children for whom social participation and treats were rare. The observing adults also valued these events – the Newcastle Courant noted the joy, for all, of seeing ‘hundreds of happy faces’.[xvi] The over-whelming theme from these examples however is the emphasis on social and class interaction. Historians need to be cautious when linking historical and spatial contexts – simply placing historic events within urban space fails to engage properly with why specific places have meaning to people in the past – yet the events detailed here reveal the importance of green space within urban settings that had reduced capacity for communal gathering. Throughout the nineteenth century, many towns and cities experienced increased social segregation of the population. The open space of urban commons facilitated use by a wider distribution of the populace, regardless of social standing, and eased class distinctions (at least temporarily) during events that enabled mass celebration and shared human experience.

While our current crisis has resulted in absence of celebratory events such as these on our urban green spaces this year, the bright lights, sounds and action associated with them will be a welcome sight to everyone in the years to come.

Dr Sarah Collins

[i] J. A. Erredge, The Ancient and Modern History of Brighton, with a reprint of “The Booke of all the Auncient Customes, 1580” (Brighton: W. J. Smith, 1867), p. 195.

[ii] Arrival of the King and Queen, Moring Post, September 1, 1830 (Issue 18634), accessed April 29, 2020, www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk.

[iii] The Triumphal Arch,Aquatint engraving drawn by A S, printed and published by W Leppard (Brighton), accessed 29 April 2020, https://sbpc.regencysociety.org/the-triumphal-arch/.

[iv] Ibid; Arrival of the King and Queen.

[v] Arrival of the King and Queen.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Erredge, The Ancient and Modern History of Brighton,p. 195.

[viii] Bath and West Exhibition to be opened at Bristol To-Day, Western Times, May 27, 1903 (Issue 16814), accessed May 27, 2020, www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk.

[ix] Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Vol. LVIII, Dec 1878 to May 1879 (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1879), pp. 217-229.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Suffragette and King, Tamworth Herald, July 12, 1913 (Issue 2344), accessed April 21, 2020, www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk.

[xii] The Temperance Gala on the Town Moor,Newcastle Courant, June 30, 1882 (Issue 10826), accessed April 21, 2020, www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk.

[xiii] Ibid.

[xiv] Ibid; Bill Weeks, History of the Town Moor (Newcastle upon Tyne: Kenton Local History Society Bulletin 6, 1994), pp. 3-6.

[xv] Weeks, History of the Town Moor.

[xvi] The Temperance Gala on the Town Moor.