A Christmas Commons Carol

A Christmas Commons Carol

A Christmas Commons Carol

A Christmas confession – I hate “The Twelve Days of Christmas”! Every year at Christmas, my mother hung a tea-towel version of the song on our kitchen door. One glance and I would be compelled to finish the rhyme in my head. Then, the terrible fate of all younger children - my siblings discovered my secret obsession and took great delight in shouting-out random lyrics before scurrying away. YES! – They tortured me. But, following extensive therapy, this year I am fighting back…

I have favoured alliteration and metre over exact numbering (it is impossible to find 12 of something!), so with some urban common’s twists and a fair bit of artistic license, I present to you “A Christmas Commons Carol”.

On the twelfth day of Christmas of Commons history

Twelve diggers digging,

Eleven Prince’s parties,

Ten lords a leasing,

Nine ladies hanging,

Eight musket balls a-flying,

Seven stones a-standing,

Six Lepers laying,

A Gold-like finger ring,

Four racing courses,

Three Roman coins,

Two bomber crashes,

And an Iron Age Hillfort-eeeee

If you enjoy light and fluffy Christmas history blogs then here is your chance to stop reading, otherwise read on for the actual history. Although not all of the above numbers match as much as I would like, each line does reference the history and archaeology of one of our four case studies: the Town Moor (Newcastle); Mousehold Heath (Norwich); Clifton and Durdham Downs (Bristol); and the Steine and Valley Gardens (Brighton). There is a rich, but often invisible component to urban commons and this month’s blog highlights some impressive examples of the material remains and the features from past human interactions with these sites.

Twelve diggers digging

The Town Moor in Newcastle is better known for pastoral activity, but agriculture has had a significant and widespread impact across the surface of the green space resulting in features such as ridge-and-furrow.[i] The use of the land for food production became particularly important during WWII following the ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign by the Ministry of Agriculture. The campaign encouraged people to transform their gardens, parks, and recreational spaces into allotments to support the war effort. In Newcastle, the city council established allotments on the Town Moor, Hunters Moor and on Little Moor. Some of these areas are still under cultivation, but old allotments are still visible on 1940s aerial photographs, and two raised parallel banks on Hunters Moor are the remains of tracks between allotment plots.[ii]

Food Production, The National Archives Allotments, Photograph by Dr Livi Dee

Eleven Prince’s parties

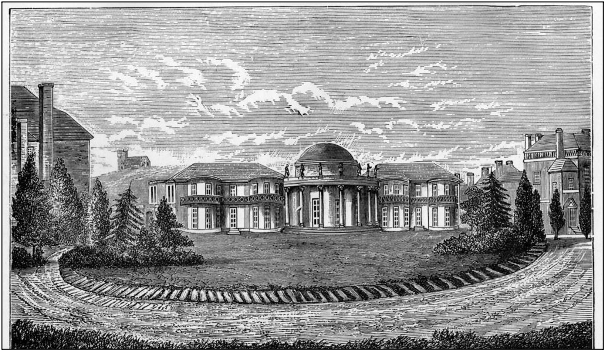

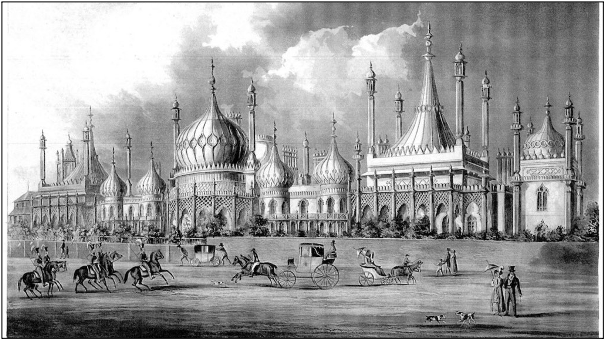

In 1783, the Duke of Cumberland (George IIIs brother), invited the Prince of Wales (later George IV) to stay with him in his house on the Steine.[iii] The following year (1784), the Prince visited again and leased a house on the Steine, which belonged to Thomas Kemp, MP for Lewes. In 1787, the architect Henry Holland carried out several alterations to the house, which became known as the Marine Pavilion and was later redesigned by John Nash (1815-23) into the Indian-style palace that survives today.

The Pavilion 1788, Society of Brighton Print Collectors (CC BY-NC 4.0)

The Pavilion 1821, Society of Brighton Print Collectors (CC BY-NC 4.0)

The construction of the Pavilion directly affected the physical space of the Steine and Valley Gardens. The Prince and his neighbour, the Duke of Marlborough, funded the construction of improvement works to stop annual flooding of the green space, but in return, the town authorities granted permission to enclose the area in front of the Pavilion. This event acted as a chain-reaction - the formerly open expanse of the Valley Gardens used for boat-storage, was gradually enclosed by housing and roads. In addition, by the late eighteenth century the Steine and Valley Gardens had become a location for summer retreat and entertainment for the Prince and his friends.

Ten lords a leasing

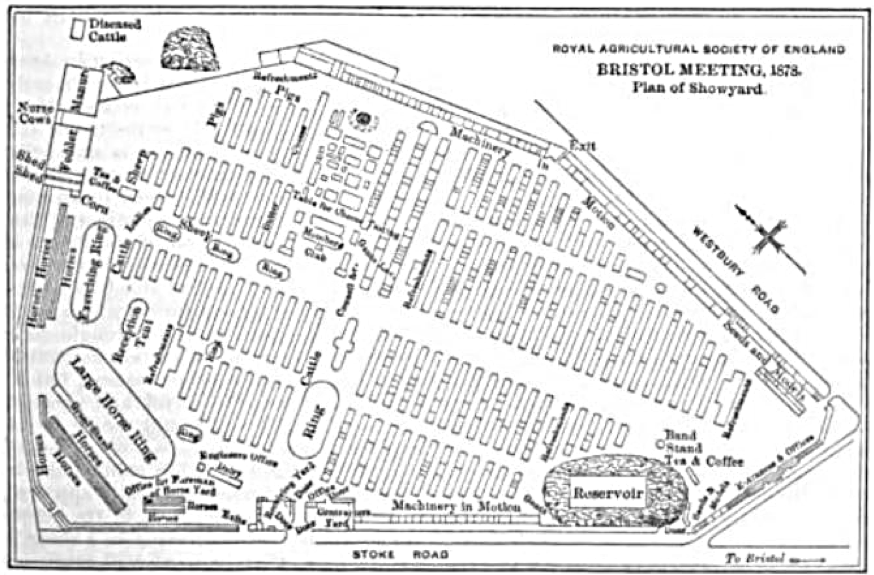

Clifton and Durdham Down were two adjoining commons within the manors of Clifton and Henbury. By the seventeenth century, four landowners (Lords of the Manor of Henbury) tightly restricted the use of Durdham Down through fines, and leased areas of land for quarrying. An area now known as ‘The Dumps’ are remaining earthworks from this period of the Downs history.

Local workers quarried the site for lead, iron, manganese and calamine. The series of earthworks (outlined in red above) look like shallow bunkers much like you would find on a golf course. Unlike nineteenth century quarries (outlined in black), these pits were not infilled. They represent a period of earlier extraction that was smaller-scale and concentrated on following specific mineral veins, which was less impactful to subsequent landscape use.

Nine ladies hanging

Unfortunately it was many more than nine - On August 21st 1650 fourteen ‘witches’ were executed on the Town Moor following the Newcastle Witch trials. There are no archaeological remains of their deaths, but Eneas MacKenzie, writing in the early nineteenth century, reported the events from an extract of the Register of the parochial chapelry of St. Andrew’s in Newcastle.[iv] The witch trials were conducted during a period of heightened suspicion that was typically targeted towards women, although not exclusively – for example, a male ‘wizard’ was also a victim of the 1650 trials. The events in Newcastle took place under the authority of the self-named Scottish Witch Finder, Cuthbert Nicholson, who was paid twenty shillings per witch captured. Those under suspicion were stripped-bare before being tested with a pin – if they failed to bleed then they were guilty. In a twist of fate, Nicholson was forced to flee from Northumberland after his methods were questioned – the pin was likely retractable so never pierced the flesh of those on trial - he was apprehended in Scotland and condemned to death by hanging, but it is believed that he was responsible for over 200 hundred deaths in England and Scotland.

Eight musket balls a-flying

Mousehold Heath has a long history of military action that has left material remains and earthworks as features of the current landscape. The Long Valley, which was used as a sheep walk between Norwich and Horning Ferry, has provided evidence for military drills and practice. In c.1990, twenty-four lead balls (Norfolk HER 53875), six lead shot (Norfolk Museums Collections - NWHCM 1973.296), and fifteen musket balls of seventeenth- or eighteenth-century date (NWHCM 1974.546.1) were found from three different locations in the Long Valley. The heath continued to provide a suitable location for military practice into the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The Heights, for example, consists of a massive earthwork of over six metres that can be found just north of the Valley Drive estate. It was a former shooting stand constructed prior to 1863 with a set of butts for shooting practice at one end (NHER 26560).

Seven stones a-standing

The earliest documentary evidence for grazing rights pertaining to Clifton Down and part of Durdham Down dates to an Anglo-Saxon charter of AD 883. The charter detailed the boundaries as running from the bottom of Eowcumbe (Walcombe Slade) to a site close to the present Water Tower. The boundary was preserved, in 1800, by way of seven merestones (boundary markers) that run across the Downs to distinguish the administrative jurisdiction of the two manorial properties.[v]

Six Lepers laying

Lazar House, Norwich, Paul Shreeve (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Lazar House on Sprowston Road, Norwich, was once adjacent to Mousehold Heath. Herbert de Losinga (the first Bishop of Norwich) founded Magdalen Chapel (Lazar House) at some point before 1119.[vi] The building acted as a hospital for male lepers and poor sick until it was dissolved in 1547, after which it was used as an almshouse until the seventeenth century. Sir Eustace Gurney restored the chapel in 1906 and it was converted into a local library branch, which is still in use today. The building consists of various construction phases and includes flint rubble with stone and some brick dressings, and a pan-tiled roof. Some, if not all, of the materials used in the buildings construction would have come from the extraction works on the heath - it is important to remember that the activities on urban commons provide archaeological evidence beyond the immediate vicinity of the green space.

A Gold-like finger ring

This copper-alloy ring (hence ‘gold-like’), of first century AD, is now in the collection of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Described as a casual find from Clifton Down, it has a D-shaped hoop that incorporates an oval bezel.[vii] The profile of a male head - with swollen facial features and coiffure, and a palm of victory - is in relief on the bezel within a beaded border frame, which is indicative of depictions of the emperor Nero (37-68 AD).[viii] The wearer of the ring probably used it as an outward expression of loyalty during Nero’s reign.

Four racing courses

All four of the urban commons studied by the Wastes and Strays project have an association with horseracing. In Norwich, this form of entertainment was sporadic and short-lived, but Brighton, Clifton (Bristol), and Newcastle had annual race meetings during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Grand Stand Town Moor (unknown date), Newcastle Libraries

The archaeological remains of horseracing is particularly striking on the Town Moor, which has a history of racing from c.1721 to 1881 when racing moved to Gosforth Park. Archaeological surveying in the 1990s demonstrated that the course was roughly oval in shape and built in two phases. The early course circumnavigated the high ground of Race Hill, but the later course was more direct resulting in a cut through the summit of the hill and the construction of an embankment, which can still be seen today.[ix] The finishing post was located by the grandstand to the north of Grandstand Road (then a track leading from the Great North Road to the stand).

Three Roman coins

Antiquarian accounts from Brighton record several discoveries of Roman coins and urns during nineteenth century improvement work on the Steine and the Level. One such example is from 1876 when workers discovered a Roman coin of Antonius Pius (r AD 138-161), one of Gallienus (r AD 253-268), and one of Claudius II ( r AD 68-270).[x] Recently, Ken Fines has indicated that there is evidence to support the existence of a small port (of unknown Roman date) at the mouth of the Wellesbourne because of foundations buried in the seabed south of the Palace Pier.[xi] The Wellesbourne ran the length of the green space so the finds are consistent with the Romano-British practice of votive offerings in association with water.

Two bomber crashes

Mousehold Heath formed the base for a number of military uses during WWII, which included training facilities for practice trench digging, a Prisoner of War camp, and the location of defensive structures such as barrage balloons. The heath’s location, close to Norwich but distant enough to reduce public safety, made the space ideal for use as a dummy airfield, complete with decoy aircraft. Aerial photography analysis by the National Mapping Programme identified six bomb craters in relation to the sites WWII uses. In addition, the heath was also subject to two WWII plane crashes. On February 12th 1942, a Hampden bomber crashed in the Long Valley whilst attempting an emergency landing at RAF Horsham St. Faith (approximately 2.5 miles to the North of Mousehold Heath). The pilot, twenty-five year old - Sgt Ernest Ivo Nightingale, was killed. Five months later, on July 25th 1942, a Bristol Beaufort crashed on the eastern edge of the Heath (a plaque marks the spot at the top of Gurney Road). All four crewmen died – they ranged in age from twenty-one to twenty-five – two from the Royal Canadian Air Force, one from the Royal New Zealand Air Force, and one from the RAF.[xii]

And an Iron Age Hillfort-eeeee

The Iron Age hillfort of Clifton (Clifton Down camp) is a scheduled ancient monument of approximately 2.6 hectares. The camp was one of three forts that lay either side of the Avon Gorge. Stokeleigh and Burwalls lay on the Leigh Woods side of the Gorge, but collectively they must have been an impressive and dominant feature within the local topography. The antiquarian John Lloyd Baker described the monument in 1818 as a set of three banks and ditches, which were dugout with considerable effort and possibly surrounded by a wall (now believed to be of dry stone construction).[xiii]

William Worcestre, writing about Bristol in 1480, believed the camp belonged to an ancient giant and that the stones that lay around the enclosure were a demonstration of its strength.[xiv] Worcestre’s observation was actually the result of quarrying that had broken up the banks. By the eighteenth century, destruction through quarrying was significant. Ironically, Sir William Draper, appointed by the Society of Merchant Venturers in 1766 as a manager to prevent exploitation of the Downs, was the worst culprit. Draper was reputed to have levelled large sections of the hillfort creating irreversible damage and disrupting later archaeological phases. This destruction continued into the nineteenth century when material was quarried from the site to provide material for new roads and for lime burning. Unfortunately, by 1873, the Reverend H. M. Scarth reported that ‘the ancient fort that once crowned the down is almost obliterated’.[xv]

The evidence recorded in this blog is just a small fraction of the archaeological finds and features that so frequently go unnoticed when we visit green spaces. Local Historic Environment Record offices have a wealth of information for those wishing to know more, and each of our sites are featured within the online records that can be found at the following:

Tyne and Wear Sitelines, Newcastle https://www.twsitelines.info/

The Keep, Brighton https://www.thekeep.info/collections/

Know Your Place, Bristol https://maps.bristol.gov.uk/kyp/?edition=

Norfolk Heritage Explorer, Norwich http://www.heritage.norfolk.gov.uk/

During what has been a very strange year, and on behalf of the entire Wastes & Strays project team we wish you a very merry and safe Christmas 2020.

Dr Sarah Collins

December 2020

[i] Ridge-and-furrow is the archaeological remains of ploughing, which (as a general-rule) have wider curves in medieval examples and straighter narrower ridges in early modern examples. For those wishing to observe the features on the Town Moor there are a number of good examples observable from the path, which passes Cow Hill. Extensive archaeological surveys of the archaeological remains of the Town Moor can be found in Lofthouse, Town Moor, Newcastle upon Tyne Achaeological Survey Report (Newcastle: RCHME, 1995), pp. 42-52.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] The Duke of Cumberland purchased the house of Dr Russell in 1779 – Dr Russell, who practiced in Brighton between 1747 and 1759, was a strong advocate of sea bathing and was considered largely responsible for the towns changing fortunes during the eighteenth century.

[iv] Mackenzie, Historical Account of Newcastle Upon Tyne Including the Borough of Gateshead (Newcastle: Mackenzie and Dent, 1827), p. 37.

[v] Goldthorpe, Clifton and Durdham Downs: A Landscape History Final Report (Bristol: Bristol City Council, 2006), p. 3.

[vi] The building history of Lazar House is detailed by the Norfolk HER service, http://www.heritage.norfolk.gov.uk/record-details?MNF631-Lazar-House-Library-and-former-leper-hospital&Index=2&RecordCount=1&SessionID=5ac103ac-ebbf-4a5b-8313-4f6d62998d3e.

[vii] Hutchinson Pennanen and Henig, ‘A Finger-Ring from Clifton down’, Britannia, Vol. 26 (1995), pp. 308-309.

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] Lofthouse, Town Moor, p. 12.

[x] Accession number: MES289, East Sussex County Council HER, https://www.thekeep.info/collections/getrecord/ESHER_MES289.

[xi] Fines, A History of Brighton & Hove: Stone-Age Whitehawk to Millennium City (Chichester: Phillimore, 2002), p. 5.

[xii] For detailed findings from Norfolk’s National Mapping Programme see, Cattermole et al. (eds.), Using Air Photo Mapping for Strategic Planning in Growth Areas: A case study from the Norwich, Thetford and A11 Corridor National Mapping Project (Norwich: English Heritage Project No. 5313, 2013). A depiction of the memorial plaque and details of the men killed can be found at, https://www.flickr.com/photos/43688219@N00/2259292426.

[xiii] Baker, ‘An account of a chain of ancient fortresses, extending through the South Western part of Gloucestershire’, Archaeologia, Vol. 19, (1818), pp. 161-175; Goldthorpe, Clifton and Durdham Downs, p. 2.

[xiv] Scarth, ‘The Camps on the River Avon at Clifton, with Remarks on the Structure of Ancient Ramparts’, Archaeologia, Vol. 44, (1873), pp. 428-434.

[xv] Ibid.