Changing Steine Victoria Gardens and the Level

Changing visualisations of the Steine, Victoria Gardens and the Level

In July 2019 the Wastes and Strays project team travelled to Brighton for our first workshop, Four Urban Commons: methodologies for engagement.[i] As the event was held on Grand Parade it provided ample opportunity to explore and consider the spatial history and character of the Steine, Victoria Gardens and the Level. What struck me at the time was the emptiness of the green space, despite the summer months. Plans to revamp the space by Brighton & Hove City Council are on temporary hold – the high fencing to protect the site in the meantime has resulted in an absence of people. However, the hope is that on completion the scheme will offer ‘a better environment, with more public space and landscaped areas’, which will have the added benefit of enhancing Brighton’s major heritage assets such as the Pavilion and St Peter’s Church.[ii]

Artistic Impression of Victoria (Valley) Gardens (left) and the Steine (right)

* Source: https://www.brighton-hove.gov.uk/content/parking-and-travel/travel-transport-and-road-safety/a-vision-valley-gardens

With this contemporary focus on increased accessibility, the plans led me to wonder about the former landscape character of this part of Brighton. A rich collection of historical visual sources that depict Brighton have survived. This material has been analysed by the Wastes & Strays project team to understand the historic development of the Steine, Victoria Gardens and the Level, as well as those using the green space. This month’s blogpost provides a summary of some of the key findings from Brighton’s artworks.

The popularity of Brighton which owed much to Prince George (later George IV) resulted in multiple artistic representations of the Steine, Victoria Gardens and the Level being produced from the late eighteenth century continuing well into the early twentieth century. An indicative sample of thirty prints, oils and watercolours was analysed to compare active functions, users, and landscape change over time. The images ranged in date from 1765 to 1910 and were selected using an online collection, The Society of Brighton Print Collectors,established by the Regency Society of Brighton and Hove, and Brighton and Hove museums and art galleries collection provided by Art UK.

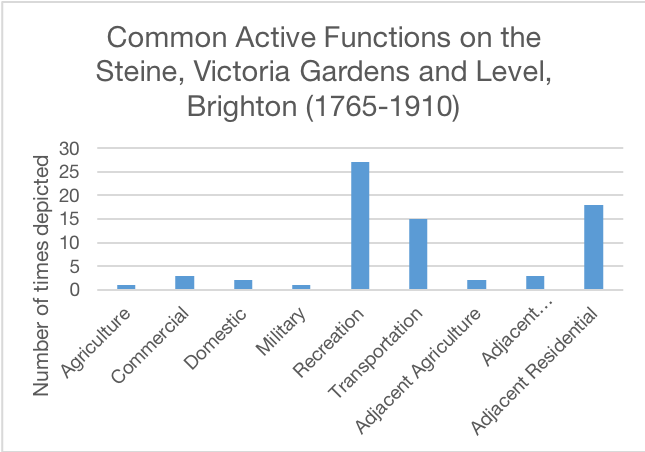

As a starting point the analysis considered the range of activities visualised by artists that occurred on the green space. These activities were largely temporary in nature, apart from ‘transportation’, in which permanent road networks physically altered the green space resulting in shrinkage of the formerly unenclosed landscape. In addition, activities occurring adjacent to, rather than on the green space – agriculture, commercial and residential uses - were recorded because artists depicted these as part of the broader landscape, impacting the general character of the area, and contributing significantly to long-term change. The number of images that depicted adjacent residential use, for example, is significant because it highlights the increased development of agricultural land to the east of the green space from the early nineteenth century onwards.

In total seventy-two activities were recorded within the thirty image sample (the results of which are shown in the graph above). Recreational use was recorded more than any other activity – twenty-seven artworks depicted people engaging in leisure. The emphasis on recreation is unsurprising. The eighteenth century saw a surge in leisure facilities of all types, and Brighton as a seaside town was ripe for recreational development, particularly after its endorsement by Dr Richard Russell in the mid-eighteenth century.[iii] The pictorial analysis strongly favours artworks from the mid-eighteenth century onwards, which skews the dataset – it was only once the green space became established as an area of elite interaction that artists were inspired to visualise it. In addition, the type of activity portrayed was determined by the view of the artist. For example, representations from the Steine looking north, east, and west were more likely to portray recreation, while those images benefitting from the height of the South Downs and looking south were more likely to include a broader range of activities including residential and transportation uses surrounding the green space. As the dataset consisted of artists who favoured northern views, from the Steine, recreation became a defining visual feature of the space between 1765 and 1910. In light of the number of surviving documentary sources that detail leisure activities taking place on the green space we can surmise that the images provide observed scenarios (at least in part), rather than merely imaginary scenes. Having said this, written sources provide greater nuance. Whereas the majority of images favoured promenading scenes, newspapers have catalogued an array of spontaneous activity. Take for example a report from the Morning Post, 9th of August 1805, ‘the fineness of the day renewed the sport of donkey riding, and airing in dashing curicles, &c. The Steyne, as usual, was covered with beauty’.[iv]

So what about other uses? Well, these were important too and reveal the continued variety of activities for which the Steine, Victoria Gardens and the Level were used. Three instances of commercial use were recorded. Two of these involved female hucksters selling perishable goods (most likely fruit), whilst the third provided an example of use of the southernmost end of the Steine for boat storage. Use of the green space for boat storage can be dated to at least the sixteenth century. J. A. Erredge’s[v] history of Brighton documented that the Steine was used as an area for boat-storage before its development into recreational grounds from the 1780s, but it is interesting that John Sotherby’s 1797 depiction (below) includes boats so close to the circulating library. If boat-storage was still happening despite ‘improvements’ funded by Prince George and the Duke of Marlborough in the early 1790s then it suggests that transformation of this space was a gradual process.

On the Steine, Brighton, East Sussex by John Sotherby, 1797

(note the row of boats in the centre of the picture to the right of the circulating library)

* © Brighton and Hove Museums and Art Galleries. Produced under a creative commons license.

Evidence of domestic practices continuing to take place on the green space during the nineteenth century is also important in showing the contribution that working class users made to the Steine and other green spaces. For example, View on the Steine, Brighton (1808)[vi] depicts three working class males in the foreground cleaning a carpet in close proximity to urban elites promenading, and A Bird’s-eye View from the Preston Road (1819)[vii] shows several washing lines in use for clothes drying on the grassed area between the current Victoria Gardens and St Peter’s Church. Such depictions of mixed-use practices well into the early nineteenth century is indicative of greater acceptance of complex spatial and social arrangements in English towns developing during the eighteenth and early nineteenth century.[viii] Whereas, by the mid-nineteenth century onwards the failure of artists to continue to represent such mixed-use activities within urban settings, such as wastes, might be interpreted as movement towards greater segregation of spatial arrangements associated with the Victorian period. This does not necessarily mean that green spaces became more exclusive, but the images do demonstrate increasing access by the middle-classes within a publicly ornamented setting, and a decline in its use as a functional working space for members of the working class.

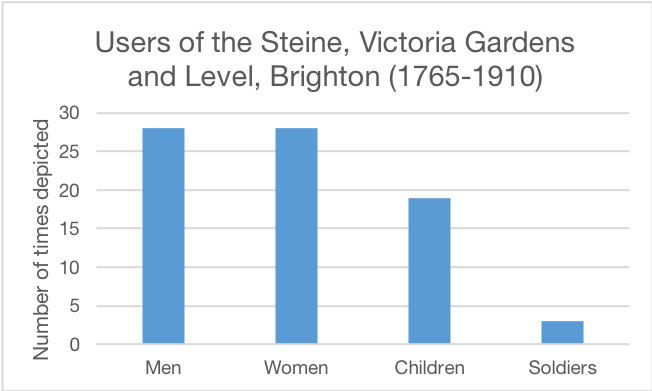

This brings us nicely to the depiction of the users of the Steine, Victoria Gardens and the Level between 1765 and 1910. Sex, age, class, and animal subjects were all considered within the analysis, the results are shown in the two graphs below.

Pictorial quality meant that the precise number of men, women, children and soldiers could not be determined. However, the artworks revealed an overwhelmingly mixed gendering of space. None of the thirty images had single-sex subjects. Instead, of the twenty-eight images that depicted figures there was an equal balance between male and female subjects. At least three of the images had soldiers who were represented both on and off duty. This group was measured separately because it represented a transient part of Brighton’s population, but nevertheless an important part of the community and attraction for tourists. Finally, it is worth observing that over half the images contained children (male and female). Five of the nineteen examples featured children at play with balls or dogs, and all examples included children with accompanying adults – these were family groups enjoying the green space as an area for recreation.

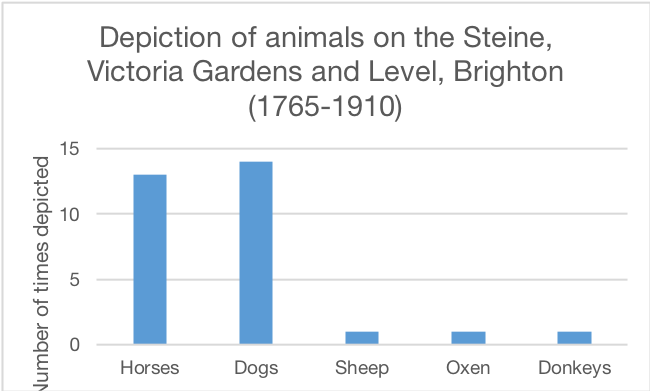

Similar analysis was undertaken of the depiction of animals within the artworks. Twenty-three of the images featured animals including horses, dogs, sheep, oxen and donkeys. On the one hand, the representation of animals might be considered negligible – a visual tool only - but it also supports the notion that the green space transitioned gradually from a working landscape with oxen and sheep to one in which there was greater reference to domesticated species such as dogs. The 1797 image Western Side of the Steyne, North of Castle Square (shown below) demonstrates this transitional landscape unmistakably. A small flock of sheep are depicted grazing on the enclosed Steine where a family group is also participating in leisure. The proximity of this view to Sotherby’s 1797 image above further supports observations that the Steine remained in use for activities other than elite recreation until at least the late eighteenth century.

Western Side of the Steyne, North of the Castle Square, Brighthelmston, 1797

* © Brighton and Hove Museums and Art Galleries. Produced under a creative commons license.

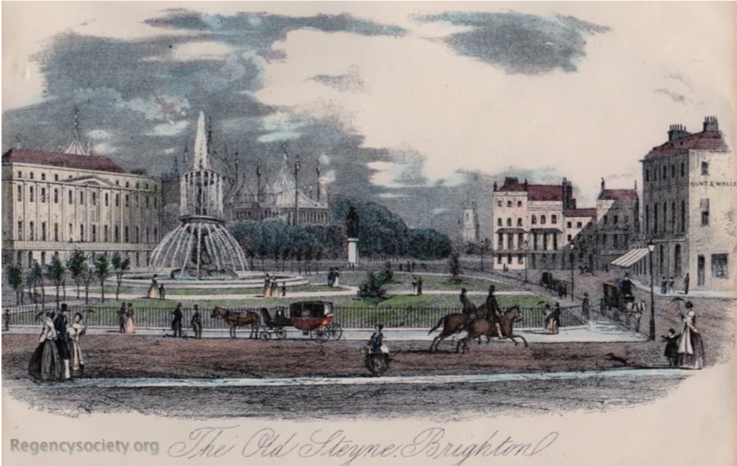

In contrast, horses were commonly depicted with riders or accompanying carriages on the road networks that increasingly surrounded the green space, and all fourteen examples that contained dogs showed them in the company of humans. One can only assume that these were intended to represent pets because of the regularity with which dogs are depicted walking or playing with humans (see the example below). So, much in the same way that the Steine, Victoria Gardens and the Level is enjoyed by families (in its broadest interpretation) today, the same held true for this green space from at least the mid-eighteenth century.

The Victoria Fountain, Brighton. Erected May 26th 1846

* © Society of Brighton Print Collectors. Produced under a creative commons license.

What the images overwhelmingly demonstrate is that this green space was a landscape of intense human activity, and even when roads and public footpaths started to dominate the space, in ways that have become controversial in modern times, images such as The Old Steyne, Brighton, 1824 (© Society of Brighton Print Collectors. Produced under a creative commons license), shown below, continue to portray the importance of this space as an area of human interaction. In fact, while the retraction of the green space has been a significant process between the 1780s and present, Brighton’s current street layout has actually preserved the east to west, and north to south extent of the original green space.

In contrast with other urban wastes, loss of green space was not the result of built structures so it would be relatively easy to reinstate the waste as it looked before the rise of leisure – with this in mind, a scheme that hopes to prioritise the pedestrian within the landscape is not necessarily a bad thing if all modern user groups can reach a compromise.

Dr Sarah Collins, Newcastle University

March 2020

[i] An overview of the event is available on this website as a blogpost by Dr Rachel Hammersley.

[ii] A Vision for Valley Gardens, accessed January 27, 2020,www.brighton-hove.gov.uk/content/parking-and-travel/travel-transport-and-road-safety/a-vision-valley-gardens. For discussion on the controversy that surrounds the plans see, Sarah Booker-Lewis, Controversial Old Steine revamp approved, February 8, 2019, accessed January 27, 2020, www.brightonandhovenews.org/2019/02/08/controversial-old-steine-revamp-approved/.

[iii] For general discussion on the rise of leisure in English towns: Peter Borsay, ‘The English urban renaissance: the development of provincial urban culture c.1680-c.1760’, in Peter Borsay (ed.), The Eighteenth-Century Town: A Reader in English Urban History 1688-1820 (London: Longman, 1990), pp. 159-187; Joyce M. Ellis, The Georgian Town 1680-1840 (Hampshire: Palgrave, 2001); Rosemary Sweet, The English Town 1680-1840: Government, Society and Culture (Harlow: Pearson Education, 1999). For Brighton specifically: Sue Berry, ‘Pleasure Gardens in Georgian and Regency Seaside Resorts: Brighton, 1750-1840’, Garden History, Vol. 28, No. 2 (Winter, 2000), pp. 222-230.

[iv] Morning Post, August 9, 1805, accessed January 28, 2020, www.go.gale.com.

[v] J. A. Erredge, The Ancient and Modern History of Brighton, with a reprint of “The Booke of all the Auncient Customes, 1580” (W. J. Smith: Brighton, 1867), pp. 182-83.

[vi] View on the Steine, Brighton (1808), accessed January 27, 2020, https://sbpc.regencysociety.org/donaldsons-library-in-view-on-the-steine-brighton/?highlight=Steine.

[vii] A Bird’s-eye View from the Preston Road (1819), accessed January 27, 2020, https://sbpc.regencysociety.org/brighton-a-birds-eye-view-from-the-preston-road/?highlight=Steine.

[viii] Sarah Collins, ‘A comparative study of urban space in Newcastle upon Tyne and Charleston, South Carolina, 1740-1840’, (PhD diss., Northumbria University, 2019); Colin G. Pooley, ‘Living in Liverpool: The Modern City’, in John Belchem (ed.), Liverpool 800: Culture, Character and History (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2006); Gregory Stevens Cox, St Peter Port, 1680-1830: The History of an International Entrepôt (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1999).