Some Concepts in Benefits Management

Concepts in Benefits Management

Benefits management has a language all its own (some would say, many languages, used by different groups and organisations), and it is worth outlining some of the key concepts.

Roles and Responsibilities

As with projects in general, there are certain roles which need to be allocated to responsible people. They include roles which extend beyond the lifetime of the project, and into the implementation and use by staff.

Roles and Responsibilities – Benefits Management

|

Role |

Responsibilities |

Active during project |

Active after handover |

|

Project sponsor |

Typically a senior individual who is responsible for the achievement of benefits. Maybe the initiator of the project, in which case they will be engaged with the problem that needs to be solved |

Strategic |

Strategic |

|

Project manager |

Point of contact coordinator to ensure that the business change management and benefits realisation activities have been defined, and appropriate people ensure that they are executed |

Operational |

|

|

Benefits sponsors |

Senior managers with overall responsibility for ensuring that specific benefits are achieved, and to provide an escalation point for the project manager and benefits manager for issues relating to that benefit |

Strategic |

Strategic |

|

Change manager |

Manager who ensures that the changes required to realise the benefits have been identified, that necessary resources are available and actions taken |

Operational |

Operational |

|

Benefits manager |

Manager responsible for ensuring that benefits measures are defined, data are available, reports a regular issued and reviewed, and that remedial actions are taken when benefits are not being realised or are below target |

Operational |

Operational |

(eHealth & Scottish Government, 2009) for roles, responsibilities in (UCISA, 2016 p.3 p.3)

Project, Programme, Portfolio

Sometimes termed P3M, the distinction between projects, programs, and portfolio is vitally important to ensuring that the benefits delivered will justify the investment.

A portfolio can be considered to be the collection of all the change projects and programmes that an organisation is undertaking. A portfolio may also apply to a funder, for example the balanced scorecard above shows the overall (high-level) benefits for the change portfolio that Apperta foundation is supporting, even though they are in different organisations. The benefits listed in the balanced scorecard are portfolio benefits, which each programme and project within the portfolio are expected to contribute to (one or more). Programs and projects may have their own benefits, which in turn contribute to these high-level benefits, but if a change programme does not contribute to any portfolio benefits, then it probably should be stopped, and the resources applied to a program that does contribute.

Programs are collections of projects, typically interdependent, that deliver a business change. Typically programs are the lowest level at which benefits are achieved. The projects within a program will typically deliver a capability; for example, a program to implement a new piece of software could include projects to: specify the software, contract to purchase the software, install/upgrade the computer equipment and put the software onto it, train staff, and implement a new way of working with appropriate reporting. Six separate projects, each with a specification/ timeframe/ budget are all interdependent (the programme would not be delivered without all of them being achieved) make up a program.

Project Management and Benefits Management

Project management is a generic term referring to the management of all three: projects/ programs/ portfolios. Project management is a structured process (ideally using one of the time-tested methodologies which includes stage-based delivery within tolerances, and exception-based reporting such as PRINCE2, APMP, PMIP) to ensure that the resources applied to change and improvement aren’t wasted.

Benefits management is a discipline within project management that means that programs are properly monitored, maximising the benefits realised. Benefits realisation is about achieving what the project set out to achieve, including savings on wasted or inefficient time, better patient care, and better outcomes for patients and staff.

Stakeholders

In healthcare, everything revolves around people: the patients, the staff, the general public, the people behind the scenes, the politicians.

When investing public money, and when making a change that could affect people, it’s important to understand this and to have a clear plan for managing your stakeholders.

A simple way to understand your stakeholders is to work out everybody who might be affected (for example, the above list, although there may be subgroups within that list), and then work out how they are affected. Are you responsible to them, you’ve invested the money? Are you going to affect their experience of care? If the effect positive, or negative? How big an effect is it?

A key part of stakeholder management is to engage – to involve the people who are going to be affected. The advantage of writing a list (and getting colleagues to put ideas) is that you can work out which are the most important stakeholders – the ones most affected, the ones who can make a decision which affect your project – and concentrate on engaging with them first.

In the tools section we have included a stakeholder management template.

There are many ways to engage with stakeholders, it’s almost a subject in its own right. You can inform through publicity (one-way), but ideally you will create a way for stakeholders to feed back and make it interactive. You can engage by email (individually), but it’s often better to create engagement events when people can get ideas from each other. It is vitally important to plan these carefully, both to make sure that negative feedback doesn’t escalate out of control, and to have messages to fill the long periods of silence when no one knows what to say.

Stakeholder management is key part of benefits management, because the stakeholders are typically far more interested in what benefits are going to be achieved, than what the project does. They want to know what it means for them, not what buttons to press. Stakeholder management determines whether your project is going to be stopped half way through, or spread more widely then you ever imagined. Although there is a requirement for health and care organisations to engage with stakeholders (including the general public) when designing a change in the pathway or services, it’s often a good idea to on engaging with stakeholders throughout the project, and into the use of the service – independent stakeholders may identify areas where a small improvement can yield a big result, and where you can record a much greater return on investment and you would without all these extra pairs of eyes.

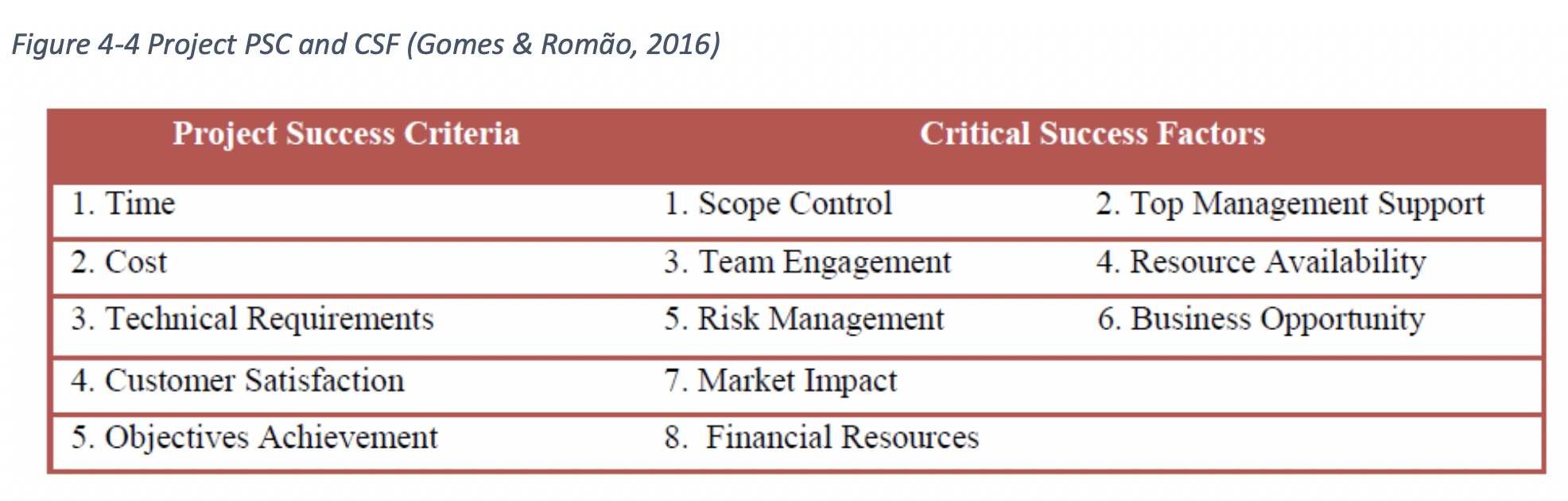

Project Success Criteria and Critical Success Factors

Every project and programme was initiated for a reason – in the main to answer a problem or take advantage of an opportunity. In healthcare, this could mean the problem of administration costs (resolved by recording information on a computer system so that it is written once and read many times) or the opportunity because of new knowledge (eg keyhole surgery was a new concept a few years ago, and improves operation success rate and patient experience, and also reduces costs dramatically.

Most projects or programmes have a single primary purpose, no matter how many additional benefits they create. However sometimes the primary purpose is not simple (eg keyhole surgery example given above), and a project may have a number of Project Success Criteria (PSC), which if they are met or exceeded, will mean that the project is a success. Very often the bar is set quite low – a reduction in hospital bed days following keyhole surgery, vs conventional (old-fashioned open) surgery, could be relatively easy to achieve, even though in financial terms the return on investment may be very high (ie the savings made in financial terms may exceed the cost of implementing the change by many times). Consequently you should expect to exceed the minimum PSC, sometimes by a long way.

Unfortunately many projects don’t have defined PSC. We don’t know what we wanted to achieve, so we probably haven’t achieved it.

So PSC are a measure of whether a project has succeeded. There’s another side to this.

Critical Success Factors (CSF) are the enablers or the things that have to be in place and/or work, for the project to achieve its PSC. CSF are required so that PSC can be delivered (Gomes & Romão, 2016; Jenner, 2014).

For example, if the intention is that all clinical activities will be recorded in the at the point of care, then a CSF would be that the means to record the clinical activities will be available. If clinical rooms don’t have computers (or the computers aren’t available to the clinician, or don’t connect to the relevant clinical system), then it’s physically impossible to record clinical activities electronically. Other CSFs could include training, willingness of staff to participate, consent from patients and service users, in addition to the ICT factors.

There are various diagrams of Project Success, including Jenner’s Greek Temple (Jenner, 2014) and the Cranfield process (Lahmann et al., 2016; Ward & Daniel, 2005) but these are complicated and should be explored once the practitioner is comfortable rather than at the start.

In summary of this section: CSF facilitate achievement & PSC measure success (Gomes & Romão, 2016)

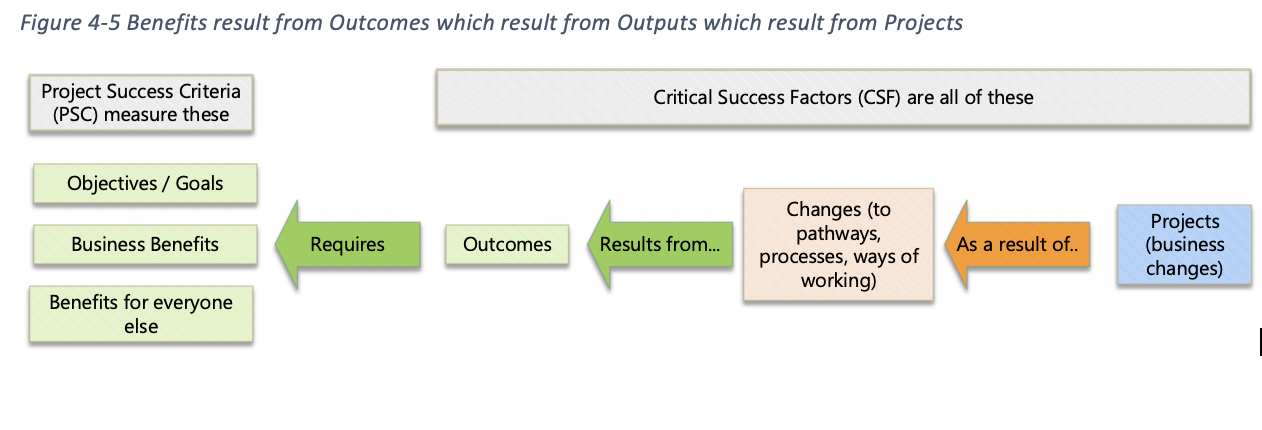

Benefits / Goals / Objectives / Outcomes : The Right Hand Side of BDN

The term Benefits can be used as a catch-all to include any of the above – Outcomes, Benefits, Goals. There are subtle distinctions between these terms, but they are largely semantic or personal preference.

It is important to understand that these Benefits can be at different levels and with different contributors. For example, a hospital (at organisation level) may have the goal to reduce readmissions within 28 days (so as to improve patient care and clinical outcomes, as well as save costs). An individual project may deliver a benefit of better patient care and clinical outcomes in its specific cohort of patients. The Benefit from the project contributes to the hospital’s overall goal because better clinical outcomes results in fewer readmissions (and so do many other projects within the hospital).

The hospital’s Goal (or objective) of reducing readmissions is a “Goal” because the hospital set it as one. It’s also a benefit because of the contribution it makes. Some maintain that benefits contribute to objectives, but the subtle difference in usage should not distract from the simplicity of a good BDN.

Benefits vs Disbenefits

Disbenefits are, as the name suggests, the opposite of benefits. For example, when a clinician records an activity onto a computer screen, they take their attention away from the patient or service user, often more than they do when recording an activity on a piece of paper. To the clinician, the advantage of recording information once outweighs the disadvantage of having to look at a computer screen. To the patient, who isn’t aware of the time the clinician spent when the patient is out of the room, transferring everything to a computer system, this may be seen as a negative. However it frees up more clinician time to arrange more appointments to see patients, and so reduce waiting times.

There is a key difference between dis-benefits and risks. Risks (both positive opportunities and negative threats) might occur, and need to be managed and mitigated. Dis-benefits are considered to be inevitable, and are typically managed or mitigated during the delivery of care, rather than during the development of the project.

Disbenefits should follow similar activities and processes as benefits management. They should be identified, categorised, quantified and measured in the same way benefits are. Often project teams are reluctant to be forthcoming with disbenefits. However, disbenefits management is invaluable in understanding what your stakeholders perceive as negative consequences of change, and help inform communications plans and realisation planning. Most projects will have some type of disbenefits, whether they are actual negative consequences of change, or a benefit that is perceived as positive by most, but another stakeholder group may perceive as a disbenefit. (IPA, 2017)

Outputs

The outputs are a simpler concept to describe. The project takes actions, and those actions lead to an output. The project to build a brick wall results in the output of brick wall: in the same way that a project to place bricks in a line and on top of each other we also result in the output of brick wall. The output is a measure of the success of the project (i.e. a planning stage, it is the planned output of the project), and an individual project could have one or more outputs.

Chain of Causality / Logic Chain

We described in 4.5 Benefits / Goals / Objectives / Outcomes. The Right Hand Side of the Benefits Dependency Network (BDN) that a particular project would result in a particular benefit. However, it is not as predictable in real life.

The outputs of a project are typically predictable; however the outcomes may be dependent on a number of other factors. In an extreme example, making the clinical system available to professionals in their consulting rooms, even the output won’t happen unless the computer hardware is in place. More subtly, if the clinical system is available, and other professionals who are involved with that patient have not updated their treatment, or the clinical system that this clinician is using has not accessed the information recorded, then the clinician providing treatment to the patient on this specific occasion may not be improving patient care and reducing risk; they may actually increase risk because of a false sense of confidence.

The Chain of Causality, sometimes termed Logic Chain, is a discipline and a process which involves scrutinising all of the inferences that one thing leads to another, and determining what other factors may be involved. It’s a term used in SROI (Minney, 2016), and it’s also useful when quantifying the benefits achieved by a particular project, to reduce double counting (where benefit is counted into the return on investment on 2 separate projects), and to ensure appropriate attribution.

The Chain of Causality can be seen as a counterpart to a project management “Critical Path”, in the sense that both pick out the most important elements, in an environment where there are a number of choices.

Benefits Measurement and Measures - Lead and Lag Indicators

Benefits can be measured in a number of different ways, depending on the type of benefit, and the most practical way to quantify the benefit.

Patient and service user experience may be measured on a Likert scale (1 … 10 or L … J). This can be reported as either an average score, “on average people were 6.5 with a range between 3 and 8”, or as a % happy “50% of people rated their happiness as ‘quite happy’ (score 7) or above”.

Numbers of appointments are measured in numbers; waiting time can be measured in minutes or weeks; clinical time spent with patients or service users can be measured as hours per week or as a % – some outcomes lend themselves automatically to a measure.

Measures of cost saving may require a calculation: the cost saving achieved by reducing the amount of time pharmacists spends entering information onto a computer system requires that we know both the amount of time saved, and the cost per hour the pharmacist, and multiply the 2 together.

The most reliable measures of the benefits of the project are the measures of what has actually happened – since these are after the event (completion and delivery of the project), they are termed lag measures (or lag indicators).

The downside of lag measures is that (by definition) they can only be measured once the project is fully delivered, and there are few opportunities to make adjustments and improve results once you have the lag measures.

Therefore many projects use lead measures to help them make decisions which will achieve the maximum benefits. The lead measures typically rely on the Chain of Causality, in that we are measuring a change in something that we are fairly confident is a good indicator of the benefit to come. For example: if we want clinicians to use a piece of software, and the number of clinicians who both have access to the software and have received training is a reasonable lead measure.

Lead measures might include employee satisfaction, which in a commercial service environment as a proven linkage to customer satisfaction, the lag measure. Reduced error rates may be a lead measure relating to safety or cost effectiveness, or may be dependent on a measure prior to that of the availability of consistent and accurate data (lead measure).

Lead measures are less reliable, but they are often more useful than lag measures because of when they are available – in time to make decisions.

The key reason for measuring benefits (using either lead measures or lag measures) is to be able to make an estimate for how much a particular project or programme contributes to the strategic objectives of the portfolio. For example in the case of Apperta, the strategic objectives or overall portfolio benefits are:

- Clinical Outcomes

- Patient Experience

- Staff Experience

- Financial Cost of Delivering Service

- Better designed software

- Driving competition.

Benefits Categorisation

Many projects and programmes will generate a huge number of individual benefits, and some people take great pleasure in drawing up enormously complicated Benefits Dependency Networks. However, the BDN is a tool, and should be as simple as is practical, for the purpose of clarity.

With anything more than 5 benefits/objectives, it’s useful to categorise the benefits so that a whole category can be reported on, as well as the individual benefits that make it up.

There are as many ways of categorising benefits as there are benefits managers, and the most important way to categorise benefits on a particular project and programme, is to align them the way benefits are categorised across the whole portfolio.

Some examples of ways to categorise benefits are given below.

Apperta:

|

Clinical Outcomes |

this will include better mobility, longer life (more years in the life), more active life (more life in the years) or reduced morbidity, reduced readmissions, reduced use of medication |

|

Patient Experience |

some of the clinical outcomes also directly relevant to patient and service user experience, including longer life and more active life. Patient experience will also include shorter waiting times, reduced pain, reduce dependency on hospital visits, faster recovery |

|

Staff Experience |

The most obvious for staff is to spend more of their week with the patient, and less on paperwork. Also: more confidence because of access to comprehensive and accurate patient records, and other improved working conditions |

|

Financial Cost |

The cost of delivering healthcare is considerably larger than the likely cost of ICT projects. Investment in computers, and software to access clinical systems, and the technology to make decisions and predictions from those clinical systems is likely to be richly rewarded by the savings in the cost of healthcare, whether through reduced use of medication to counteract side effects, reduced rework and readmissions, or create a health amongst patients service users and the population resulting in lower demand |

|

Better designed software |

When the users of the software are funded to have time to be involved in the design of the software, the result will be screens and forms that are more efficient in everyday use. In a 15 minute appointment, a saving of one minute on each screen to find something or to complete a form can have a significant impact. It may enable appointments to be reduced to 12 minutes, which means 5 appointments per hour instead of 4, with the consequential impact on waiting times. |

|

Driving competition |

It is widely thought that many of the larger existing suppliers of systems to the health service are exploiting their position and making more profit than they strictly need to reward their investors and fund research and development. The barriers to entry for new providers have been high. By bringing in competition and choice, providers will compete on quality and service as well as price, releasing resources for use in delivering patient and service user care. |

Infrastructure Projects Authority (IPA):

|

Cash Releasing |

Benefits that can be measured, where the savings can be realised. The health example will include reduced use of medication, or reduce the length of hospital stay |

|

Non Cash Releasing |

Benefits that can be measured, where the savings can be realised in cash terms but the financial savings can’t be taken out of the budget. An example would be a saving of 15 minutes of administration time per day, which may add up to a lot of time over a large workforce, but on an individual basis is unlikely that the working day would be reduced by 15 minutes to realise the savings |

|

Quantitative |

Benefits that can be measured, but do not typically have a cash equivalent. Numbers of appointments, or waiting time. In most cases, with the right skills, a chain of causality could be built to show how the benefit can be measured in terms of savings |

|

Qualitative |

Soft benefits: for example patient or service user experience, or staff satisfaction, or quality of life. However, as described above, in reality these can be measured, and as far as possible projects should not claim that all their benefits are “soft” |

(IPA, 2017)

Maturity in Benefits Management

“Maturity” refers to the capability of the organisation to deliver benefits management. The maturity tool available from the Praxis website (Praxis Framework, 2015b) consists of a series of questions, but it’s included here because it is quite instructive about what you should have in place in order to deliver benefits consistently.

Benefits management should:

- define benefits and dis-benefits of the proposed work;

- establish measurement mechanisms;

- implement any changes needed in order to realise benefits;

- measure improvements and compare to the business case.

Level 2 attributes (maturity) include:

- benefits are quantified and documented. There is evidence supporting the estimates of benefit quantities.

- Financial benefits are valued to documentation shows the reasoning behind the valuations.

- Lunch realising benefits exist and are updated throughout the life-cycle.

- There is some measurement of pre-change metrics that this may be inconsistent. Benefits reviews may be left to individual business-as-usual units.

Level 3 attributes (maturity) include:

- full benefits profiles are prepared for benefits. These are reviewed throughout the life-cycle.

- New benefits profiles are produced throughout the life-cycle of new benefits identified.

- There is a clear link between updated benefits profiles and business case.

- Sophisticated techniques are used to value non-financial benefits and documentation shows the reasoning behind the valuations.

- All benefits realisation activities are included in a separate benefits realisation plan was a section of the main project or programme delivery plan. These plans are regularly updated and interfaces maintained.

- Metrics affected by change of base light before changes applied and cracked throughout the realisation period.

- A full benefits review is conducted on completion and actual net benefit as compared to the original business case.