SA1.2

Summary of main structural phases

Based on a stratigraphic interpretation of the structures and of the modules of the brickwork, Pelliccioni (1974) originally identified seven structural phases:

- Phase 1A: structures made out of tufa

- Phase 1B: structures made out of tufa

- Phase 2A: opus testaceum structures

- Phase 2B: opus testaceum structures

- Phase 3: Building of the baths, second century

- Phase 4: Reconstruction of the baths, Severan

- Phase 5: Domus with small baths, third century

- Phase 6: Construction of a circular building and its adaptation to a baptistery, early fourth century

- Phase 7: Reconstruction of the baptistery during mid fourth century.

Krautheimer rejected Pelliccioni's intepretation of phases 6 and 7, suggesting instead that the circular structure had to be considered the foundation of the octagonal baptistery, a suggestion shared by Olof Brandt and Federico Guidobaldi in their research on the elevation of the octagon. The scholars have also suggested that the octagon was built during the reign of Constantine and that it was restructured with the rising of the roof and the addition of chapels in the fifth century.

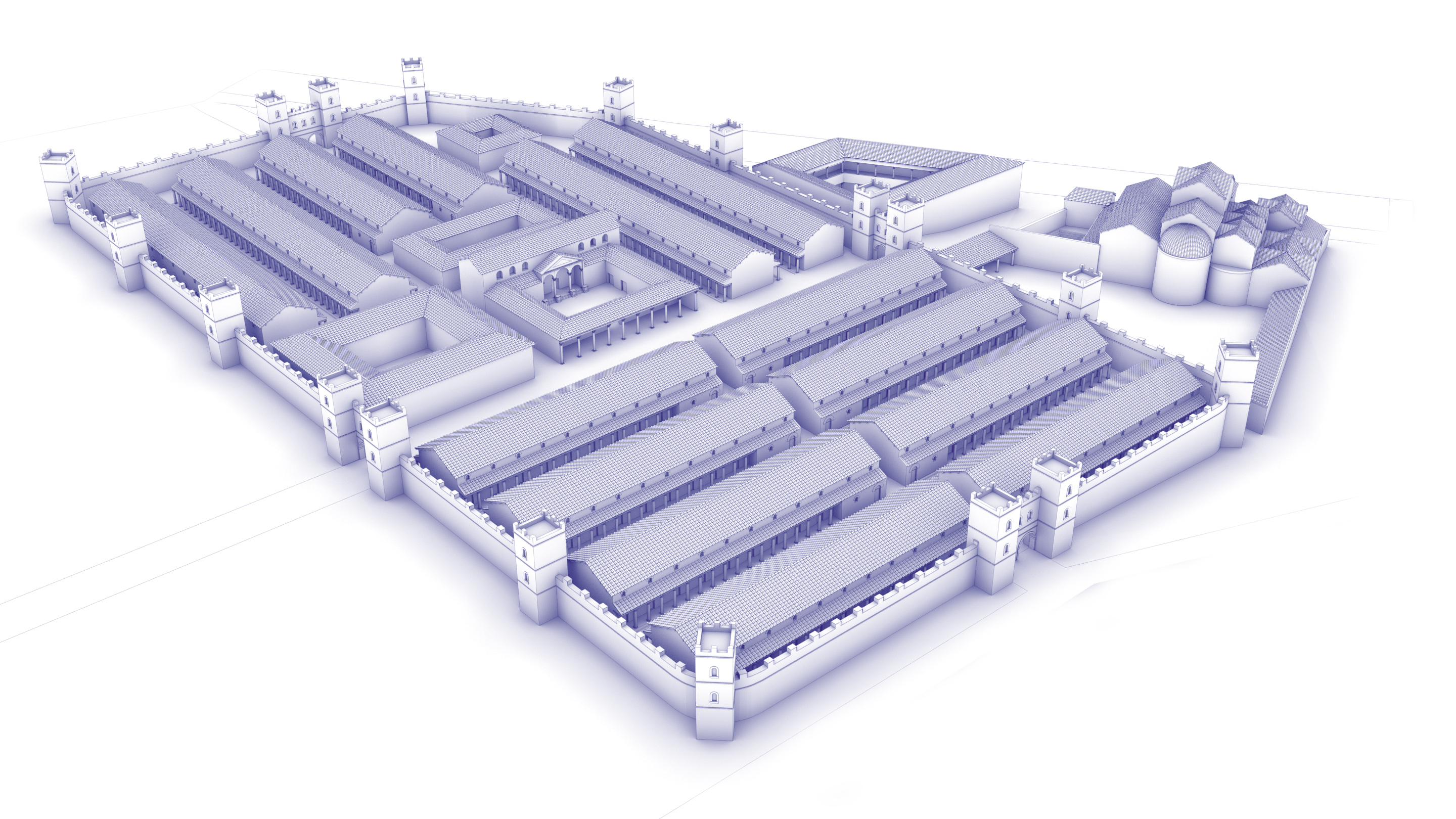

Rome Transformed research: bringing together below the ground and above the ground structures

Our research has not only revised Giovenale's and Pellicioni's site interpretation suggesting a new phasing for the structures below the ground, but has also brought together information from below and from above ground, assessing the complex in it entirety. We suggest therefore the following phasing and chronology:

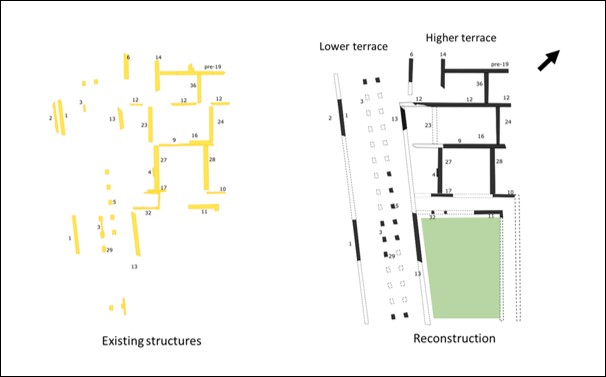

- Phase 1: A terraced domus (from Trajan onward). During phase 1 a terraced domus was built, divided in two terraced blocks sloping from east to west. The building was made of a higher, eastern terrace with rooms designed along a main axis and delimited to the west by a wall. The second portion of the property developed on a lower, porticoed terrace to the west and roughly placed 1 metre below the eastern terrace.

Above: Phase 1. Existing structures (left) and reconstructed plan (right) (Ravasi in preparation)

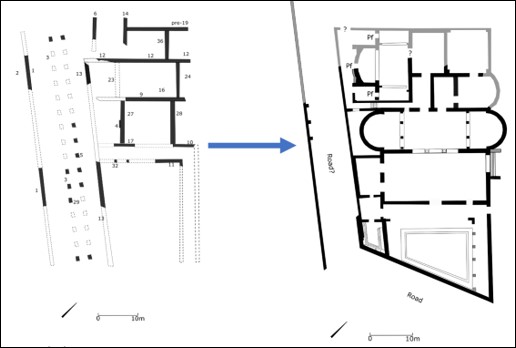

- Phase 2: Building of the baths reusing the pre-existing terracing for the placement of service corridors and praefurnia (initiated by Septimius Severus and completed during the reign of Caracalla).

Reconstructed plans of Phase 1 (left) and Phase 2 (right) (Ravasi in preparation).

- Phase 3: Gradual transformation of the thermal complex, with the demolition of the hypocaust in the old caldarium (now transformed into a service room) and its replacement by smaller hot pools. Restructuring of the frigidarium and adaptation of one of the original warm rooms into a cold room with a fountain. Structural phase 3, likely encompassing distinct actions of adaptation of the building to a wider range of uses, dates from the late third-early fourth century, showing evidence for the use of the complex by Christians from the early fourth century.

- Phase 4: Defunctionalization of the baths, partial demolition and burial of the western side of the complex. Rising of the ground floor in the whole complex and construction of an octagonal room above the western portion of the frigidarium, abutting the eastern structures of the baths. Replacement of the western piscina of the frigidarium by a circular water basin. Partial reuse of the baths' hydraulic infrastructure. The eastern half of the baths survives, but the large hall is reduced in size, while the eastern piscina of the frigidarium is walled up. Some of the former bath rooms are transformed into partially underground service spaces. Research on the chronology of the octagonal room is still ongoing.

- Phase 5: addition of the chapels of St. John Baptist, St. John Evangelist and of the Holy Chross.

- Phase 6: Adaptation of the large hall into the chapel of S. Venanzio, by walling up its original western access and building of the apse.

Provocations

References

Bosman L., Haynes I.P. and Liverani P. (eds.) (2020), The Basilica of Saint John Lateran to 1600, The British School at Rome Studies series, Cambridge University Press.

Colini, A.M. (1944), Storia e topografia del Celio nell’antichità, Atti della Pontificia Accademia Romana di Archeologia, serie III, Memorie, 7. Vatican City, Tipografia Poliglotta Vaticana.

Giovenale, G. B. (1929). Il Battistero lateranense nelle recenti indagini della Pontificia Commissione di Archeologia Sacra. Studi di Antichità Cristiana, Rome.

Jansen G., Ravasi, T., (in press), Balneum under Lateran Baptistery, multi-seater of Severan period, in Koloski-Ostrow, A.O., Neudecker, R., Jansen, G. (eds.), Sixty-six Toilets in the Ancient City of Rome: sanitary, urbanistic, and social agency BABESCH suppl., Peeters: Leuven (Belgium).

Pelliccioni, G. (1973). Le nuove scoperte sulle origini del Battistero Lateranense (Memorie della Pontificia Accademia Romana di Archeologia, serie III 12, 1). Vatican City, Tipografia Poliglotta Vaticana.

Aknowledgements

We wish to thank first and foremost colleagues at the Vatican Museums, notably Barbara Jatta, Giandomenico Spinola, Sabina Francini and Leonardo De Blasi for facilitating access to the scavi.

- Structural Analysis (data collection and database input): David Heslop and the Lateran Project team

- Structural Analysis (site interpretation and phasing): Thea Ravasi

- Hydraulic infrastructure: Elettra Santucci (we wish to thank Duncan Keenan Jones for his insight and suggestions)

- Scanning and data processing: Iwan Peverett, Alex Turner, Gianluca Foschi, Thea Ravasi

- Mortar analysis: Mauro La Russa, Luciana Randazzo, Thea Ravasi, Sofia Vagnuzzi

Thea Ravasi (last updated on 31/10/2023)