Abstracts

Paper Abstracts

Panel 1: Enslaved mothers: maternal bodies in comparative perspective

Stephanie Jones-Rogers (University of California, Berkeley): Black Milk: Maternal Bodies, Wet Nursing, and Black Women’s Invisible Labor in the Antebellum Slave Market.

This paper examines the market that white southern mothers created for enslaved wet nurses and the impact their actions had upon enslaved women and their children. White mothers routinely sought out and procured enslaved wet nurses to suckle their children, and when they did so, they created a demand for the intimate labor that such nurses performed in southern households. They further commodified enslaved women’s reproductive bodies, their breast milk, and the nutritive and maternal care they provided to white infants. Their desire and demand for enslaved wet nurses transformed these women’s ability to suckle into a form of largely invisible, skilled labor, and created a niche sector of the slave market that supplied white women with the laborers they sought.

Formerly enslaved people were the individuals who spoke most cogently about white women’s use of enslaved wet nurses. Enslaved women who served as wet nurses, formerly enslaved men and women who were kin to these women, and those who merely possessed first-hand knowledge of the practice, described how important these women were to white mothers and their children. Formerly enslaved people also described the ways that white women’s decisions to use enslaved wet nurses often broke the already fragile, yet sacred bonds between many enslaved mothers and their children, and frequently intensified familial trauma within their communities. Enslaved mothers endured painful separations that did not occur in southern slave markets, but the marketplace nevertheless profoundly shaped these severances.

Formerly enslaved people’s reflections about white mothers’ demands for enslaved women’s maternal labor is critical for another reason. Their remembrances make it clear that southern slave markets and slave-owning households frequently converged in ways that scholars of the slave market and the domestic slave trade often miss, and that women, particularly mothers, played vital roles in forging connections between the two. White mothers assessed the labor needs of their infants, went to the slave market or published advertisements in local newspapers in order to hire or purchase healthy young women, and then brought them into their homes to perform maternal labor. In a host of ways, this paper elucidates the formal and informal markets through which enslaved wet nurses circulated, it examines the roles white women played in these markets, it challenges scholars’ masculine conceptualizations of skilled labor performed by enslaved people in the South, and it demonstrates that southern slave markets touched even the most intimate spaces of slaveholders’ lives.

Martha Santos (University of Akron): “Slave Wombs,” “Slave Mothers” and the Naturalization of Slave Reproduction in Nineteenth-Century Brazil.

This paper examines Brazilian slaveholders’ and politicians’ discourses on “slave wombs” and “slave mothers” within the context of the 1831 legal suppression of the African slave trade, the 1850 final cessation of the illegal traffic, and the post-independence debates on the need to reform slave relations to make them more compatible with a modern, capitalist world and a liberal political framework. It demonstrates that elite planters concerned with the replenishment of captive laborers and resolved to maximize profits from the existing population of slaves regarded enslaved women’s sexual and generative lives as well as their mothering labor as central to the procreation of a creole population of slaves that would gradually replace African captives imported in the trade. At the same time, continuous concerns with slave rebellion and fears of the outpouring of “barbarian” African men through the illegal traffic intensified the symbolic value and political significance of enslaved women and enslaved mothers as “pacifiers” of an unruly population of enslaved men. All in all, this paper argues that it was not slavery’s demise through free-womb laws that inaugurated a preoccupation with female slave reproduction and that this concern was not related only to the struggle for freedom, as the existing scholarship on emancipation implies. Instead, concern with enslaved women’s reproduction and mothering labor was central to the redefinition of the institution of slavery in Brazil during the nineteenth-century. By centering on what historian Jennifer Morgan calls “the impact of women on slavery,” this paper also sheds light into several mechanisms through which the framework of slavery produced and naturalized a gendered category of “slave mothers” with specific work and social functions, and into the social construction, instead of “natural” assignation of the task of reproducing and stabilizing the slave labor force to female slaves precisely during the period of increasing de-legitimization of the institution of bondage in Brazil.

Jenifer Barclay (Washington State University): “Bad Breeders” and “Monstrosities”: Racism, Childlessness and Congenital Disabilities in the Era of American Slavery.

This paper will examine: the racial dimensions of childlessness and the birth of congenitally disabled children in antebellum America; the competing narratives that whites created to explain these occurrences among black and white women; and the impact of these racialized discourses on perceptions of gendered medical conditions later in the nineteenth century. While numerous scholars have considered how enslaved women’s reproduction fed into and maintained North American slavery, few have examined childlessness outside narratives of resistance.[1] A disability history lens illuminates how enslaved women’s inability to bear children, whether real or imagined, shaped their lives in overwhelmingly negative ways. Failure to live up to owners’ expectations in the reproductive realm led to severe consequences, such as being labeled a “bad breeder” and sold away from family, loved ones and friends to unsuspecting traders. White physicians and slaveholders drew on stereotypes of black women as hypersexual to cast childless enslaved women as deserving of and to blame for their “condition.” They also applied this same racist logic to other aspects of enslaved women’s reproductive lives. Physicians often claimed that congenitally-disabled enslaved newborns were the products of their mothers’ sexual lasciviousness, connecting the presence of disability at birth to enslaved women’s presumed promiscuity and echoing older religious ideas about “monstrous births” as signs of God’s displeasure for immoral behavior. In sharp contrast, physicians accounted for white infants’ congenital disabilities with newly emerging medical explanations or by suggesting that white mothers were afflicted with “uterine sympathy,” whereby a pregnant woman was so shocked by a disturbing image or event that a corresponding physical mark was transferred to the fetus she carried. The deeply racialized rhetoric that surrounded childlessness and the birth of congenitally disabled infants in the era of American slavery laid the groundwork for racialized medical knowledge to emerge later in the nineteenth century around feminized “nervous conditions” like hysteria.

Cami Beekman (Rice University): “‘Erring Women’: Abortion, Infanticide, and Co-producing Culture and Science in the American South.”

“I loved to watch his infant slumbers; but always there was a dark cloud over my enjoyment. I could never forget that he was a slave. Sometimes I wished that he might die in infancy . . . O, the serpent of Slavery has many and poisonous fangs.”

Harriet Jacobs’ slave narrative sheds light on the ways slaveholders sexually harassed and abused enslaved women. She insists in Incidents in the Life of A Slave Girl “the forbidden topic of the sexual abuse of slave women can be included in public discussions of the slavery question.” Her account shows that the sexual exploitation slaveholders inflicted on enslaved women shaped their identities and experiences as sexual objects, female patients, and mothers. These unique enslaved women’s experiences as both sexual objects and female patients forced many women to provide gynecological care to themselves and others while coping with motherhood in slavery. At the material intersection of bodily enslavement, motherhood, and sexuality, enslaved women in the American south became creators, healers, and destructors of human life. In “‘Erring Women’: Abortion, Infanticide, and Co-production in the American South” I investigate the co-production of nineteenth-century gynecology and obstetrics with social ideas about enslaved mothers and fertility control.

My research will examine enslaved women and their babies’ impact on the integration of socio-political and scientific ideas. This story is one of co-production in that the use of fertility control by enslaved women was a process mutually produced with gynecological science in a very scientifically experimental period of American history. This paper will contribute to the discussion at “Mothering Slaves” by focusing on several of the international research network’s outlined questions: “How did enslaved women experience motherhood and the care of their own children?”; “What practices and understandings of mothering did enslaved women bring with them from African societies?”; and most directly, “What was the role of abortion and infanticide in slave societies? Should these practices be considered together? To what extent did they take place, and how far can they be usefully considered a form of resistance?”

Panel 2: Images and representations of enslaved mothers

Fernando de Sousa Rocha (Middlebury College): Mothering Slaves in Machado de Assis’s Narratives.

In this presentation, I analyze two of Machado de Assis’s narratives that touch on the topic of slaves’ motherhood. The first one is the poem “Sabina,” which appeared in 1875 in the volume Americanas, comprising poems that reflect the New World identity of a newly founded nation. The second one is the short story “Pai contra mãe” [Father Versus Mother], which appeared in the volume to be published last during his lifetime, Relíquias de Casa Velha (1906). In this last volume, Assis included, as he explains in his “Advertência” [Warning] to readers, unpublished texts that constituted, in his view, “relics, memories of one day or another.” The poem “Sabina” recounts the story of a slave who falls in love with her young master only to see him marry a woman of a social standing similar to his. Pregnant, Sabina attempts suicide but falls short of killing herself because of her unborn child. Motherhood, in this case, saved the female slave’s life and, in turn, also saved the child’s life. “Pai contra mãe,” on the contrary, focuses on a slave catcher who, in order to save his own son, captures a runaway female slave who is pregnant. While dragging her back to her owner, the slave catcher causes the female slave, Arminda, to abort. In this presentation, I attempt to account for the different destinies that Sabina and Arminda face: saving an unborn child and giving birth to a stillborn baby. In order to do so, I will situate one, the poem “Sabina,” within the context of the New World identity that the volume Americanas proposes, in following the Romantic construct of the American political-continental reality. In this sense, Sabina’s motherhood must be read in tandem with that of Iracema, the famous female protagonist of José de Alencar’s foundational novel Iracema (1865). To my mind, it is within this American context that the poem “Sabina” puts into play the abolitionist ideals and, particularly, the image of motherhood, often used strategically to increase the number of supporters for the abolitionist cause. As for the short story “Pai contra mãe,” my reading will focus on the notion of relics and remembrance. The question I will be pursuing in this section is: how come, once slavery is abolished and enslaved Africans and Afro-Descendants emancipated, what remains as a relic is precisely the stillborn child of a slave, death as the offspring of slavery?

Chloe Faux (Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Paris): “The mothering gaze”: salvage, empowerment, and the black female slave/

The daguerreotype, an early iteration of photography, was deemed a "gift to the free world" yet through Louis Agassiz’ 1850 slave daguerreotypes, the technology gained notoriety in imaging the bodies of the unfree. In Camera Lucida Roland Barthes asks: what sort of affective relationship does one have to a photograph of a person when it all that remains after that person has died? He continues on to describe the photograph as possessing an unforgiving temporality; first it coexists with the subject, but eventually outlives her. He writes: “Whether or not the subject is already dead, every photograph is this catastrophe.” Considering Barthes question in relationship to Louis Agassiz’ images of slaves in Columbia South Carolina, which, according to records, depict only fathers and daughters (Jack is Drana’s father, and Renty, Delia’s), I frame the evisceration of motherhood as the catastrophe of slavery. In slavery“ ‘kinship’ loses meaning, since it [could] be invaded at any given and arbitrary moment by the property relations” (Spillers 1987: 74). This paper is a meditation on contemporary readings of the images that retroactively attribute dignity and honor to the photographed slaves (e.g. Rogers 2010). By engaging with Hortense Spiller’s definition of “motherhood” as the bond of certainty enforced by the life-affirming gaze exchanged between mother and child (Spillers 1987), I ask to what extent to such readings deny black feminine self-possession, where “ blackness is defined…. in terms of social relationality rather than identity” (Hartman 1997: 56)? How do such attempts at “salvage” converge with or diverge from the maternalism of white feminist abolitionists that transformed Sojourner Truth into a feminist icon? By juxtaposing Truth’s cartes de visites and Agassiz’ daguerreotypes, I draw connections between the black female body and the performance of freedom and enslavement within liberal humanist frameworks.

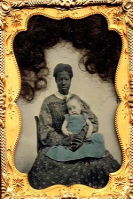

Kimberley Wallace-Sanders (Emory University): Slavery and Other Mothers: Black Mammies, Nannies and White Children in Portraiture.

Between 1840 and the early 1900s, hundreds of photographic portraits were made of African American women or young African American girls holding white children; the children of the white families, slave-owners before in antebellum American and employers afterwards. These portraits reveal an astonishing and complex intra-racial and inter generational intimacy between family members and servants, offering original insights into American family life.As an extension of my study Mammy: A Century of Race, Gender and Southern Memory (Michigan UP, 2007), this new book project represents a shift in my scholarly interests from the cultural representations of “the mammy” to the actual African American women (and often young girls) whose daily lives were focused on caring for white children.

My paper emphasizes the poses are also clearly reminiscent of the traditional “mother and child” genre in paintings and portraiture. Here is the significant difference: the white mothers of the children are nearly always absent, as are any children of the African American women. As a result, these portraits clearly establish a new genre of portraits, one of “other-mother” and child.

My scholarship takes on the nanny and child portrait as a subject with tremendous possibilities; each portrait represents a completely unique microcosm of power dynamics reflecting race, gender, class, status, and age. This portraiture study intertwines African American history, and visual culture to produce a coherent and persuasive scholarly framework foregrounding the earliest and most consistent visual documentation of mammy-child relationship. My paper demonstrates how ambrotypes, daguerreotypes, professional studio portraits and informal family photographs reveal portraiture to be a powerful, and largely ignored resource for documents about slavery and motherhood. The portraits reveal that beyond the southern plantations type of “Black Mammy, these ‘Black nanny with white child’ portraits were produced throughout the antebellum North and South.

There is currently no full-length work combining a large selection of portraits of black women and white children with a rigorous analysis of how these portraits can serve as valuable resources providing visual representation of white children and their black caregivers. The fundamental argument of my research is that this early scholarship ultimately determines that portraits of slaves reveal more about the photographer than about the subjects themselves. In contrast, my work places the enslaved women, many of whom had children of their own while taking on the enormous work of childcare for white families, at the center of the discourse.

Sample Portraits:

Figures 1-4 (left to right)

Figure 1. Photographer unknown: subjects unknown, quarter plate ambrotype - c. 1857-61.

Figure 2. Unnamed Negro nurse asleep with baby on her lap, Langmuir Collection, MARBL Emory University.

Figure 3. “Nanny with children” - ca. 1895. Maryland Historical Society Figure.

Figure 4. “African American Nanny and her White Charge.” (Visible bruises on Nanny) Cowan’s Auction House.

Alison Donnell (University of Reading): Contesting Thistlewood: enslaved subjects and the limits of representation in Joscelyn Gardener’s Creole Portraits II and III.

Joscelyn Gardener¹s Creole Portraits II and III issue a provocative and carefully crafted contestation to the journals of the slave-owner and amateur botanist Thomas Thistlewood. In so doing, they bring several troubling but necessary questions into view. How do we represent the violence and violation of slavery without repeating its spectacular effect? How do we speak about subjects lost to history and yet not entirely unknown? How can we make visible the systems of representation that support an unequal distribution of authority, knowledge and power?

The often cited quantitative analysis of Thistlewood¹s 3,852 acts of intercourse with 138 women extracts the raw data from his thin yet seemingly faithful record of sexual acts and points purposefully towards the transactional nature of such encounters. While Thistlewood¹s journals make raced and gendered bodies seemingly available to knowledge, incorporating them within the colonial archive as signs of subjection, Gardener¹s portraits disrupt these acts of history and knowledge. Her artistic response marks a radical departure from the significant body of scholarship that has drawn on the Thistlewood journals to date. Creatively contesting his narratives¹ dispossession of Creole female subjects and yet aware of the problems of innocent recovery, her works style representations that retain the consciousness and effect of historical erasure. Through an oxymoronic aesthetic that assembles a highly crafted verisimilitude alongside the condition of invisibility and brings atrocity into the orbit of the aesthetic, I will discuss how these portraits force us to question what is involved in bringing the lives of the enslaved and violated women back into regimes of representation?

Panel 3: Women’s perspectives on freedom and abolition

Crystal Webster (University of Massachusetts, Amherst): In Pursuit of Autonomous Black Motherhood: Northern Black Women's Writings on Womanhood, Motherhood, and Childhood.

Recent scholarship on black women’s history has unearthed the nuanced nature of nineteenth century black womanhood; a construction that simultaneously ascribed to while actively subverting nineteenth century white Victorian constructions of womanhood as political acts of resistance. However, the efforts by which antebellum Black women constructed womanhood as inextricably tied to their expressions of motherhood and claims on behalf of their children have received less scholarly attention. Initiated by Susan Paul, black women abolitionists such as Harriet Jacobs, Maria W. Stewart, Mary Ann Shadd Cary and Frances Ellen Watkins Harper contributed to a rhetoric of Black motherhood and childhood that established the vital role of Black women and children in the politics of the free Black Northern experience, challenging popular tropes of the powerlessness of the suffering enslaved mother. Influenced by the wave of scholarship on Black women abolitionists and the discovery of new texts authored by these women, this paper examines the writings and activism of Paul, Shadd Cary, and Watkins Harper and argues that with their constructions of motherhood, these women sought to reclaim the Black mother’s autonomy over her children in an era in which a mother’s authority within and outside her home was not only shaped by social and legal disenfranchisement but also was one in which a mother was denied security of both her own freedom and that of her children. Though Northern black children were nominally free, their childhood experiences were marred by racialized treatment in ways that denied them access to the era’s romantic and sentimental characterizations of white childhood. Black women writers and activists constructed black childhood and motherhood in ways that challenged their subjugated racial status both within and outside of the enslaved South by representing Black mothers as possessing specific authority over their home and children, and by representing black childhood as religiously pious and socially innocent. This paper also explores the pedagogical usage of these texts, arguing that they functioned as spaces for the cultivation of a collective black political consciousness of childhood and motherhood that were both subversive and radical, challenging what we consider to be the historical role of black women and children in the Abolitionist, religious, and racial uplift movements of the antebellum era.

Natasha Lightfoot (Columbia University): “So Far to Leeward”: Disrupted Ties of Motherhood in Eliza Moore’s Freedom Journey.

My paper centers on the 1836 freedom petition of Eliza Moore, an Antiguan-born domestic who traversed the Atlantic on several occasions as a result of her bondage. She strategically utilized the news of emancipation’s 1834 passage in the British Caribbean to facilitate her self-emancipation from Danish St. Thomas via travel and return “home.” She was taken around 8 years old to England with her owners, and returned to Antigua at 13, when she was immediately sold to an estate owner in Danish St. Croix. From there she was sold again to St. Thomas. She changed hands a few times in St. Thomas, to an hotelier and then another planter. During those years she also had 3 sons, the first fathered by her first master in St. Croix, a second freed by his father and a third who remained enslaved with her. In 1836 she learned of British emancipation at the same time that she heard of her last owner’s intent to sell her and her son to Puerto Rico. Moore then sent a desperate plea to her family in Antigua to obtain the proof of her birth to validate her claim to freedom. Moore’s petition is eventually successful but her experiences raise intriguing questions about black travel experiences and the particular forms of exploitation at work in women’s enslavement.

This paper parses Moore's letter to her sister in 1836, which vividly tells of her many travels throughout the Atlantic world. In particular I hone in on certain forms of duress she only implies that she endured in her lifetime of bondage, namely sexual abuse and the possibly complicated relationships to the children that resulted from such violence. Her references to her experiences with motherhood are fleeting, and thus the sacrifices she may have made to have her children, to secure their freedom and to eventually free herself by removal from the last place of her enslavement can only be imagined. I hope to think through what the archive cannot tell us about the experience of motherhood under the distress of bondage, and how enslaved people’s pursuit of emancipation can at once serve to strengthen and yet disrupt family ties.

Sean Condon (Merrimack College): Margaret Mercer on motherhood and slavery.

In the antebellum United States, the interstate slave trade fueled an expansion of slavery that daily threatened family connections, while at the same time the cultural construction of motherhood began to emphasize the central role that mothers played in nurturing their children. These two trends contributed to an important source of sectional division: a central part of the abolitionist claim that slavery was immoral and illegitimate hinged on slavery’s threat to and destruction of the family ties of the enslaved, while southern critics of the abolitionists either denied these criticisms or tried to turn them around by emphasizing the corrosive effects of the emerging industrial order.

This paper examines the writings of Margaret Mercer, a prominent advocate of the African colonization movement. Born into a slave-owning family in Maryland at the end of the eighteenth century, Mercer emancipated the slaves she owned, and became for a time quite dedicated to the cause of African colonization. Many of Mercer’s arguments in favor of colonization stressed the supposed benefits that would accrue to mothers, children and families, while at the same time she downplayed or ignored the family separations that colonization would almost certainly entail. One especially important aspect of Mercer’s argument was that the expansion of slavery in the Americas developed out of a lack of meaningful family (and especially maternal) ties in West Africa.

While the colonization movement failed to live up to the expectations of Mercer and other supporters, the ideas that Mercer developed became an important (if underappreciated) source of racialized conceptions of motherhood in the nineteenth-century United States.

Panel 4: Children in Slavery and Freedom

Jane-Marie Collins (University of Nottingham): Emotion and Interest: re-evaluating childhood manumission, Salvador da Bahia, 1830-1871.

One of the most consistent claims made about manumission in slave societies across the Americas is that women and children were over-represented among the freed; that is to say, women and children were granted manumission in numbers disproportionate to their numbers among the enslaved. In addition, interpretation of the statistical prevalence of women and their children in manumission has often fallen back on feelings of affection on the part of slaveowners. In this sense, acts of manumission of women and children have tended to be associated with feeling and emotion, which somehow transcended rights and claims to slaveownership founded in interest and rationality.

Thus, the aim of this paper is to examine the historical forces behind the demographic disproportionality in manumission through the nexus of the enslaved mother and freed child. The focus here is on childhood manumissions from the city of Salvador da Bahia for the period 1830-1871, that is, before the Free Womb Law changed the legal premise for freedom suits for children of enslaved mothers. The approach adopted to interpret and analyse childhood manumissions aims to simultaneously expose and subvert the problematical way in which slaveowner prejudices have been transferred onto the objects of their prejudice and fashioned into a narrative of affective relations in which the enslaved mothers of manumitted children have been rendered at best compromised but at worst complicit in the perpetuation of the prejudices from which they, or more likely, their enslaved children benefitted in acts of manumission.

As such, the task of analysis and interpretation of childhood manumissions is undertaken here not so much with the aim of redressing the balance of agency and power between slaveowner and enslaved mother and children, but of foregrounding the imperatives of the latter against the legal prerogative of the former. Thus, this paper re-casts the notion of affective relations in childhood manumissions in particular by examining the prevalence of children in manumissions through the lens of enslaved motherhood, within an historiographical framework and historical context where the enslaved-child/freed-child forms both the subject and site of contestation over the meaning and value of the economic and the emotional in the history of the slave family in Brazil. As a major site of contestation in slave-master relations too, the enslaved mother-freed child nexus provides the formulation of an alternative approach to understanding the prevalence of children in manumission in Brazil and, by extension, the prevalence of mixed race women among the freed too.

Laura Candian Fraccaro (Universida de Estadual de Campinas): Freed women and their children on guardianship records, Campinas, second half of nineteenth century.

Motherhood has become a central subject for slavery studies. Women not only faced a pitiful situation of seeing their offspring being mistreated but also the challenge to achieve freedom for themselves and their kids. In Brazil, once freed these women often confront with a new problem. Their children could be taken away by Justice and sent to legal guardians. The legal guardianship was justified as necessary by authorities who frequently stated the mother’s behaviours as inappropriate for the constant drunkenness, poverty or immorality.

In the second half of Nineteenth century, the guardianship turned out to be a way to arrange the child labour. (AZEVEDO, Gislane. 2007, p.4) These kids had to work for their legal guardians and usually were treated as slaves despite the fact of being free. Their mothers went on trial to regain custody of the children. There was also the possibility of making a complaint about the treatment the minor was receiving in order to change the legal guardian.

Even being written by clerks, these requests as well the trial records regarding the legal guard enable the researchers to have access to these women’s speech about freedom, their children’s right and also motherhood. This paper aims to analyse these probate records and to look in detail how these women managed to keep their children and protect them from abusive legal guardians. To accomplish that, I chose Campinas (Brazil) as a study case. Campinas along the nineteenth century was an important producer of coffee and sugar and had an impressive slave population. Besides this scenario, Campinas has archives which make possible the historical research. The chosen method was nominative record linkage because it allows a reconstruction of biographies of individuals and has as the main purpose to follow over the years and on different sources these women and their children. Trial records and other sources as manumissions are used in this paper.

Rachael Pasierowska (Rice University): “This is a thoroughbred boy”: Exploring the lives of slave children and animals in the Atlantic World.

The early nineteenth-century lithograph “Le diner ao Bresil” by the French artist and traveller, Jean Baptiste Débret, depicts a white slaveholding couple dining at a sumptuously laden table. Three elegantly dressed black slaves wait on the couple. As the husband remains almost indifferent to is wife’s presence, Débret notes how the latter distracts and amuses herself with her little “dogs”, or rather two small black infants. The painter goes on to detail how such little “dogs” were at liberty to eat succulent treats, which the white mistress passed down from her plate. At the age of five or six, however, such pampered children were returned to the slave quarters, to begin a much harsher and realistic life: that of a Brazilian slave. The mistress’s sweets were replaced with the overseer’s switch. Débret remarks of such children’s indignation to this new turn of events as they undoubtedly consequently became aware of the realities of slavery and the inferior social status that thereby accompanied them.

This study builds on research from an earlier project in which I argued that North American slave children became aware of their slave status in what was in effect a three-part process. The present paper looks to the experiences of Afro-American children from across the Atlantic World, exploring the extent to which young slaves constructed a knowledge or an understanding of their social standing through the lens of the animal world. From their young eyes, recognising that they were black and enslaved, and therefore inferior to their white playmates, was a difficult stage within the lives of enslaved black children. The metaphorical and visual depictions in children’s immediate environments better enabled children to comprehend this newfound social status. For example, stories of Brer Rabbit from the antebellum South, Anansi the spider from the Caribbean, and the numerous animal jongos of South-East Brazil provided a series of metaphors that spoke to children of the system of slavery from across the Americas. In a more literal sense, other slave children drew analogies between the system of slavery and themselves through visual observations of happenings around the plantations. Thus, a whipped relative might bring to mind the image of a whipped mule.

The final part of this paper looks to the image and role of slave mothers; as slave children statistically lived in closer proximity to their maternal, rather than paternal parents. Slave mothers found themselves in a situation where they were often unable to protect their children from this ground-breaking realisation. Indeed, the moment of realisation often was instigated by slave owners as they proceeded to treat their chattel like livestock. But, despite their lack of power, mothers were able to “cushion” the shock of such revelations. Returning to Débret’s image, we see the slave mistress and her two black “dogs.” Across the Atlantic World, slave mistresses might adopt the more paternalistic role of “mother”, albeit in a way that was more representative of the relationship between master and pet. When attempting to gain a better understanding of the intricate lives of slave children and their early years, animals occupied a very significant, and hitherto, unstudied role.

Panel 5: Enslaved mothers on plantations and beyond

Dawn P. Harris (Stony Brook University): Mothering from the Interstices: The Plantation Economy and Enslaved Women’s Parental Authority.

One of the ways in which the Cuban poet and slave Juan Francisco Manzano inserted his mother into his biography, and into the plantation economy, was by revealing her powerlessness to stop him from being beaten. In his biography, Manzano retold an incident when he was punished for getting back to the plantation late. He recalled that leaving town one night, he fell asleep on the coach that was taking him back to the plantation, and the lantern that he was holding fell from his hand. When he realised that the lantern had fallen, Manzano jumped out of the coach and went to fetch it. Left behind by the coach, Manzano was forced to find his way back to the plantation. When he finally made it back, he was grabbed by the overseer Señor Silvestre and led to the stocks. Manzano noted:

Upon seeing me, she [his mother] tried to ask me what I had done, when the overseer, who demanded silence, endeavoured to stop her, refusing to hear of pleas, entreaties, or gifts; irritated because they had made him get up at that hour, he raised his hand and struck my mother with his whip. I felt this blow in my heart…

My mother and I were led to the same place and locked up. There we moaned in unison. (p. 51, The Cuba Reader).

Through this quotation, Manzano revealed a pernicious feature of enslavement: the usurpation of parental authority and its replacement by the draconian plantation. Thus, this paper looks at where slave mothering, parental authority, and the plantation economy collided. This “collision” meant that enslaved mothers often did their mothering from the “interstices”, that is to say, from the spaces left over by a system that had been established as the paterfamilias of the slave family.

Specifically, this paper pays attention to the ways in which enslaved mothers’ authority and their ability to save their children from the vagaries of the plantation were erased from a socio-economic system that had no need for cooing and coddling Black mothers. It therefore addresses a number of key questions: How did enslaved women “mother” when their femininity and humanity were continually questioned?; How did enslaved women “mother” when their authority had been co-opted by the plantation and the plantation economy?; and, how did enslaved women “mother” when they had been written out of motherhood under strictures like “partus sequitur ventrem”?

Mariana de Aguiar Ferreira Muaze (Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro) Motherhood experiences in captivity: an analysis of family, maternity, and childhood on the big plantations of the Paraíba Valley (Brazil) and Mississippi Valley.

Through a comparative perspective, this presentation will focus on the analysis of the experience of slave motherhood on the large plantations located in the counties of Vassouras (Vale do Paraíba/Brasil) and Natchez (Mississippi Valley/USA), between 1820 and 1860. During the nineteenth century, in the context of the "second slavery" (Tomich, 2005), these regions became, respectively, the world's largest suppliers of coffee and cotton, consolidating themselves as areas of economic expansion closely connected with the European capitalist market and slave labor. The expansion of the capitalist economy reformulated the sense of time and space in these areas, bringing an increase in the volume of the slave trade (across the Atlantic and internally), and changing the dynamics of slave families. How did the experiences of slave families, childhood and motherhood change during this new context? What were relations like between mothers and their children in captivity during the second slavery? What issues surround slave motherhood on big plantations? Were there differences between slave mothers who worked inside and outside the big houses? Was slaves’ maternity necessary for the continuity of the slave system in Brazil and USA after the end of the Atlantic Slave Trade? These are questions that can help us understand experiences of motherhood in captivity.

Lucia Bergamasco (University of Orléans): Enslaved mothers and motherhood in the western US Border States.

The WPA interviews for Kentucky, Missouri and Tennessee systematically afford information about mothers in slavery (a question on parents figured in the official questionnaire sent to local interviewers), although with varied emphasis, on motherhood and maternal care. Fugitive slave narratives and ex-slave narratives (some published well after emancipation) also provide information on both topics, as the protagonists often relate their experience with or about their mothers, or testify to the surrounding realities of child bearing and motherhood in slavery. Thus, drawing on the rich documentary corpus of WPA interviews and fugitive slaves narratives, I, shall explore on the one g hand, how distinct -or not - with respect to the plantation South, the experience of motherhood was in this region where farms were prevalent over plantations -but where sale of enslaved men, women, and children occurred frequently ; on the other, how the many aspects of motherhood in slavery were remembered and represented. This will be in continuity, as it were, with my survey on the peculiar features of slavery in the Border States presented at the May 2015 conference On the Many Faces of Slavery in Montpellier. The paper will close with two case studies of active maternal intervention in the freeing of daughters in Missouri as recorded in the fugitive slave narratives by Lucy Ann Delaney and Mattie J. Jackson.

Heather Cateau (University of the West Indies): "Management of Motherhood" - Reproduction in 18th Century Caribbean Societies

The Decline Thesis has examined the issue of insufficient labour or a "shortage" of labour on the sugar plantations. Historians like Lawrence et al have dealt with this peculiar” numbers game", and others like Higman have instead focused on actual increases and decreases on the plantations. There is need for more focus on the specific role of enslaved women as well as the nature of their involvement in these topical historical discussions. It is within this context that this paper locates itself within the outlined discussion by focusing on the issue of ‘Management of Motherhood’. However, this is done with the added caveat of recognizing also the enslaveds’ personhood within the analysis. This suggests that we should perhaps refer to the attempt at “Management of Motherhood”. The paper argues that not only were increases within the enslaved population a concern for sugar management (especially by the second half of the eighteenth century and with the abolition of the British slave trade in 1807), but that sugar management policies itself sought to actively institutionalize ‘Reproductive Management’ as a feature of what it perceived as a long term sustainability plan for the preservation of the industry. This was extended into attempts to “Manage Motherhood”.

The paper progresses by first interrogating the issues surrounding natural increase and child rearing on the plantations. Secondly, it links these strategies to overall planter managerial policy. Thirdly the paper concludes by commenting on the often overlooked issue of agency which the enslaved women held over their own bodies and offspring, even though they were customarily defined within the literature as "chattel". This third issue is most important because it focuses an analytical lens on the child rearing practices of the day. This multifaceted approach allows the paper a final assessment of the effectiveness and overall impact of this attempt at “Management of Motherhood”. Plantation papers, and diaries will form the basis for discussion. These will be complemented by examination of legislative changes, account books and contemporary books and letters. Ultimately the paper seeks to provide a new perspective into motherhood during the slavery period by juxtaposing policy and agency in the Caribbean reality in the eighteenth century.

Panel 6: Rape and Interracial Relationships

Mariana Libanio de Rezenda Dantas (Ohio University): African Mothers and Pardo Children: the formation of mixed-race families in eighteenth-century Sabará, Minas Gerais.

The rise of historical demography in the 1960s and 70s, followed by a rich scholarship in the field of family history in the 1980s, has contributed much to our understanding of family formation in colonial Brazil. These studies pointed to a high rate of illegitimate births, female- headed households, and relationships of concubinage. Attempts to explain these patterns of family life turned both to family history in Portugal and to the implications of slavery and race relations in the colonies. While comparisons of illegitimacy rates and concubinage in Portugal and colonial Brazil suggested a transatlantic tendency of family formation outside of formal marriages, studies of slavery and race argued that these social practices and ideas helped to impede marriages and family formation among certain segments of the colonial population. Both scholarlships have enriched the field of colonial Brazilian family history by highlighting cultural links between colonial and metropolitan societies, as well as the relevance of slavery to historical analyses. Yet, while providing structural explanations for the profile of colonial families, these studies did not always reveal the more intimate and daily actions that shaped colonial family life. Moreover, they often overlooked the role played by some of the key actors in these family dramas: black mothers. In my current research I have taken up the study of family history to explore the formation and experiences of mixed-race families in colonial Minas Gerais. Often the result of informal relationships between African-descending women and white, Portuguese men, these families had to navigate the implications of concubinage and African descent to the social standing of members of their descending generations. They thus reveal much about family life in colonial Brazil as a major pillar of social relations and change. Additionally, they highlight the vital role played by African-descendant women in the development of social and economic family strategies of survival and success. If accepted, this conference paper will focus on this latter aspect of my current research. Through the use of notarial documents from the town of Sabará, Minas Gerais, it will trace the formation of mixed-race families and elucidate the role African women – and not merely Portuguese practices, white fathers, or colonial circumstances – played in shaping and maintaining family life. In this manner, it will help demonstrate the relevance these women had in the social and economic ascent of what became the demographically dominant segment of the mineiro population: pardos.

Meleisa Ono-George (University of Warwick): Interracial Sex, Motherhood and the Movement for Civil Equality in Jamaican Slave Society, 1829-1833.

In the spring of 1830, a series of articles published in the Watchman and Jamaica Free Press, a newspaper and public platform for many discussions amongst the free community of colour, both men and women engaged in dialogue about the prevalence of interracial concubinage and prostitution throughout the island of Jamaica. Much of this dialogue focused on the impacts that these forms of sexual-economic exchange had on the community’s efforts for civil equality, but also who was to blame for its pervasiveness in slave society. While many discussed black and mixed race concubines as the victims of white men’s lust, equally discussed was the role that mothers had in the continuation of this practice and the degradation of young women of colour. As one correspondent asked, ‘what must the heart of the parent be, who could sell her child for the purposes of prostitution!—who could throw her to the dregs of society at once, and put her down among a class of debased beings, from which she can never rise to that appellation of a virtuous and an honorable women.’[2] This paper will explore the changes discourses around interracial sex, respectability and motherhood. I argue that in the midst of the movement for civil equality and abolition amongst the free people of colour, women who engaged in interracial sex were demonized as unfit mothers and hindrance to larger community of colour.

Andrea Livesey (University of Liverpool): Enslaved Mothers and the Children Born of Rape in the Nineteenth-Century US South: Trauma, Attachment and Survival.

The power fostered by the institution of slavery meant that a culture developed in the US South whereby men could sexually abuse women without repercussions or accountability. Over time, this meant that the sexual abuse of women became normalised, legitimised and endemic. The Federal Writers Project (FWP) interviewed thousands of elderly formerly enslaved people in the 1930s, and a significant percentage of these interviewees revealed, or implied, that they had been children born of rape. This paper analyses this testimony alongside nineteenth-century slave narratives and modern sociological and psychological theory in order to investigate the relationship between enslaved children and their abused mothers.

Psychological studies have shown that the trauma of rape continues to have a significant impact on the primary rape victim (the mother), long after the original attack. Mothers in this situation often show a distinct lack of parental adjustment and interpersonal sensitivity. In addition, the negative effects of psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder impact severely on the development of the child. This paper, however, demonstrates that enslaved women and their children actually displayed remarkable levels of survival.

Rape as a tool of war and social control has tragic effects at any time, but children born of rape were so common under slavery that, especially in the later period, most enslaved people would have been affected in some way. Precisely because of the scale of abuse, the evidence builds a picture of a slave sub-community that was understanding, supportive, and resilient. This paper investigates the close relationship that persisted amongst enslaved women and their children in spite of the widespread sexual abuse of both. I will present evidence that enslaved mothers not only survived abuse themselves, but also ensured that their daughters were prepared for the tragic realities of enslavement, thus minimalizing the risk of certain psychological disorders linked to extreme trauma. Daughters were given the emotional tools to cope with any future abuse, and a supportive network in its aftermath. While not all enslaved women were able to survive sexual abuse, the process just mentioned certainly helped a significant number of enslaved mothers and their children to go on to form loving marriages and family lives without being significantly affected by the ‘soul murder’ described by Parent and Wallace, and later Nell Irvin Painter.[3]

Panel 7: Enslaved mothers, slavery and freedom

Cassia Roth (UCLA): From Property to Person: Fertility Control in Pre- and Post-Emancipation Rio de Janeiro.

The abolition of Brazilian slavery in 1888 changed the legal status of enslaved women from property to person. Due to Brazil’s gradual emancipation process, however, final abolition did not drastically change the lives of many formerly enslaved women in Rio de Janeiro, as urban slaves had long benefited from relative physical and social mobility (Graham, 1988). Moreover, historians of slavery and the family have demonstrated that in the lead-up to abolition, enslaved women successfully engaged the courts to fight for their rights and those of their children (Graham, 2003; Cowling, 2013). While scholarship has analyzed the larger gendered implications of emancipation, less attention has been paid to abolition’s legal implications on fertility control. Exploring sources on abortion and infanticide in pre- and post-emancipation Rio de Janeiro, this paper examines the impact of abolition on the visibility and criminalization of fertility control. It argues that slavery may have protected many enslaved women from state intrusion into their reproductive lives due to their legal status as property.

In the nineteenth century, the Brazilian state most likely did not prosecute enslaved women for fertility control due to the contradictory legal status of enslaved women and their fetuses as both person and property. Under slavery, infanticide could have been considered both a crime against a person and a crime against property. In the first scenario, the state would press charges, but in the second, slave owners could take matters into their own hands. The paucity of judicial documents relating to fertility control in the nineteenth century can be seen as one example of its invisibility in the public sphere. In contrast, the post-emancipation period provides numerous judicial documents investigating fertility control. After the abolition of slavery (1888), the passage of the 1890 Penal Code, and the expansion of the Brazilian state, in particular the police, fertility control became the subject of increased judicial inquiry. I contend that in early- twentieth-century Rio de Janeiro, women who may not have been prosecuted for fertility control in the nineteenth century due to their enslaved status now found themselves in court. The institution of slavery may have protected vulnerable women from state prosecution. While final abolition might have had a lesser influence on enslaved women’s mobility, economic livelihood, or familial ties, it did have serious implications for who could be prosecuted for fertility control. The modernization of the Brazilian state proved contradictory in relation to women’s reproduction.

Marília B. A. Ariza (University of São Paulo): Child laborers and freed mothers: slavery, emancipation, labour and motherhood in the city of São Paulo.

The transformation of slave labour was a central issue in the articulation of the long process of gradual emancipation in the Atlantic slavery world over the 19th century, deeply interfering in the freedom experiences of former slaves and fomenting the formation of a large reserve of dependent laborers. Resting on the reiteration of social relations based on exploitation and subordination, this process created faltering entries in the realms of freedom to the formerly enslaved. Not only the formal exit from enslavement but also the limitations imposed by precarious forms of freedom defined the real possibilities of "becoming free" after emancipation. The families of enslaved and freed people were at the center of the policies developed to preserve the control over emancipated laborers. Taking part in a wide and varied range of impoverished workers, freed men, women and their children engaged in precarious labor arrangements that preserved the dynamics of exploitation bequeathed by slavery, restraining the limits of their freedom experiences. Based on the analysis of work contracts and judicial records, this paper discusses the impacts of the above-mentioned policies on freed mothers and their children in the city of São Paulo (Brazil), in the second half of the 19th century. It debates the creation of a cheap, disciplined and tutored workforce through the recruitment of impoverished children of freed mothers. As we intend to demonstrate, the regimentation of these underage laborers implicated their forced removal from maternal custody. Either because of their squalid living conditions or because of the imposition of court orders, laborer women, impoverished and curtailed in their autonomy, were compelled to give up their children. Supporting the policies of mandatory enlistment of underage workers and the fractionation of their family ties, discourses on maternity and education based on bourgeois notions of family emerged in Brazilian courts, stating that freed and enslaved women were unable to exercise the maternal virtues necessary to the upbringing of a disciplined and morally apt workforce. At the same time, however, freed mothers in São Paulo appropriated and reshaped these ideas into a vocabulary of maternal rights, which became a platform for their attempts to reclaim the custody of estranged children in the municipal court of law.

[1] On the importance of enslaved women as reproductive laborers, see Deborah Grey White, Ar’n’t I a Woman?: Female Slaves in the Plantation South (New York: W.W. Norton & Company); Jennifer Morgan, Laboring Women: Reproduction and Gender in New World Slavery (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), and Marie Jenkins Schwartz, Birthing a Slave: Motherhood and Medicine in the Antebellum South (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006). In terms of gynecological resistance, early scholarship includes Barbara Bush’s “Hard Labor: Women Childbirth and Resistance in British Caribbean Slave Societies,” History Workshop, No. 36 (Autumn 1993): 83-99 but this topic is also taken up by Jennifer Morgan in Laboring Women and by Sharla Fett in Working Cures: Health, Healing, and Power on Southern Plantations (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002). For an example of scholarship dealing specifically with the history of childlessness in the United States that virtually ignores the experiences of enslaved women, see Margaret Marsh and Wanda Ronner, The Empty Cradle: Infertility in America from Colonial Times to the Present (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996).

[2] The Watchman and Jamaica Free Press, 24 April 1830.

[3] Painter, Southern History across the Color Line, pp. 15-40; Parent and Wallace, ‘Childhood and Sexual Identity under Slavery’, pp. 363-401.

This site is no longer being maintained.

This site is no longer being maintained.