Roman Objects

Roman gods and domestic religious practices

“In a corner I saw a large cupboard containing a tiny shrine, wherein were silver Lares, and a marble image of Venus, and a large golden box, where they told me Trimalchio’s first beard was laid up”

(Petronius, Satyricon, 29)

Roman domestic religious practices were not necessarily a simplified version, reduced to superstition, of official religious practices. On the contrary they reflected complex and articulated notions and beliefs, deeply rooted in archaic practices and visually enriched by elements often derived from Greek culture. Gods presided over a variety of aspects of the daily lives of those who lived in the house, the pater familias (head of the house), his wife and children, and the numerous slaves and servants that lived in the house. In addition to embodying the owners’ status and social position, houses were also at the heart of their private devotion: they contained the physical spaces for worship (the earth and the altars) and the paraphernalia used to carry out the daily rituals, but they also held the memory of the rituals and the ceremonies performed by the household.

Lares were among the many divinities worshipped by the Romans in the private realm of the house, together with the Dii Penates (literally gods of the penus, the household provision, but by extension gods that protected the household), the Genius (the spirit of the pater familias and later of the emperor himself). Their origin was unclear to the Romans themselves, who worshipped them as protectors of the fields and as household and family gods. As such they had special honours in every house and a key role in family affairs. As benign, deified ancestors, the Lares watched over the main family activities and presided over the most important moments and passages of status in the life of its members: adolescents offered their bulla to the Lares when becoming adults (Persius, Satires, 5.30-31); brides offered a coin to the Lar of the new home (Varro, De Vita Populi Romani, 1.2 in Nonius33.L) or burned incense and dedicated garlands of flowers to the Lares who protected the nuptials (Plautus, Aulularia, 385-287); Ovid even mentions the gift of weapons to the Lares by an old man, no longer fit for war (Ovid, Tristia, 4.8.21). The written sources also record epithets designating their various areas of watch: Lares familiares (of the family), compitales (guardians of crossroads), praestites (guardians of the city), agrestes (protecting the fields), viales and permarinis (watching over travellers by road and by sea respectively).

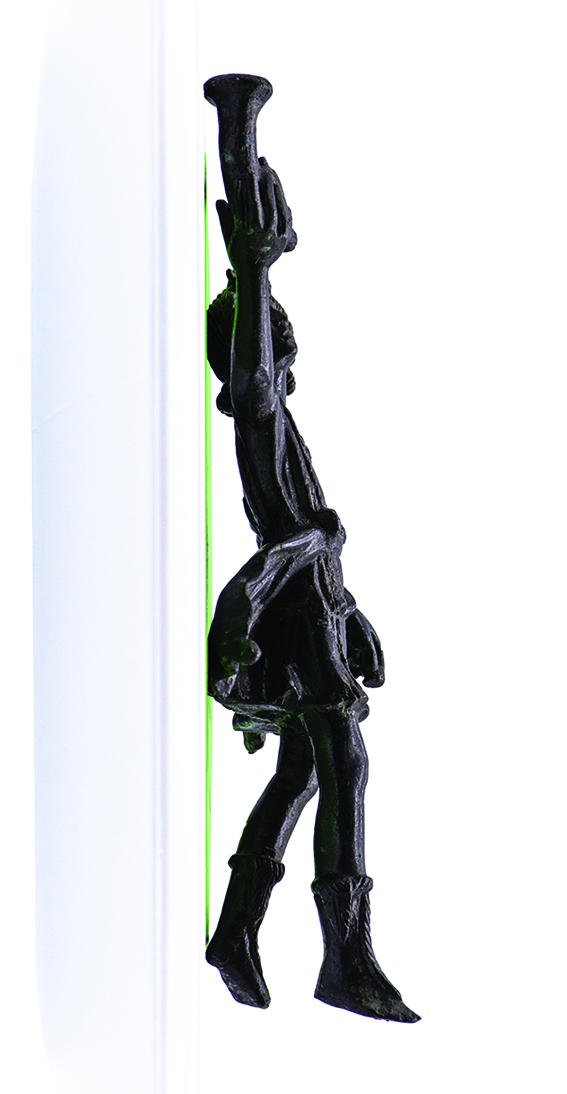

If their origin has to be found back in the religious world of Archaic Rome, their image, as we know it from the evidence provided by sculptures and paintings found across the Roman world and in particular at Pompeii and Herculaneum, developed in the Late Hellenistic period and is modelled on other divine figures that shared a similar protective role with the Lares. For example the Dioscuri, from which they likely derived their twin nature. Among the earliest images of the Lares are those painted outside the houses in Delos, dating to the second half of the 2nd century BC when the Roman authorities granted the Greek port duty-free status and where many roman merchants lived and operated. The Lares are usually represented while dancing or standing, with a young appearance, wearing garland of flowers or leaves, a short tunic, high shoes made of feline fur and a mantle, raising the drinking horn (rhyton) or a cornucopia in one hand, and a bucket, an offering plate (patera) or a branch of laurel leaves in the other. The statue of the Lar from Herculaneum (n. inv. 76721/1443) shows the god with these exact features, as a young boy in a dancing position, with a short tunic floating from the movement and holding a rhyton in his right hand.

Domestic worship extended to gods and goddesses that entered the private realm of Roman domestic contexts for different purposes. Fertility and life expectancy were, for example, of huge concern in the ancient world. Symbols of fertility therefore abounded in the houses and the gardens of many families in Pompeii and Herculaneum, embodied by statues and paintings of the god Priapus, with his large phallus, and of Venus, the goddess of erotic love, sexuality, and fertility. Venus could appear in a variety of ways and attitudes and with a variety of attributes that changed over time and according to type of cult. The naked Venus, represented standing while covering her modesty with her right arm and holding her drapery in the left, was an incredibly popular model in antiquity. Her origin lays in the artwork of the Athenian sculptor Praxiteles (active around 375-330 BC), who produced a sculpture of Aphrodite to be set up in the shrine of the city of Cnidus. From the 2nd century BC, the model became incredibly popular and was replicated endless times: in life-size copies and smaller versions, in marble, bronze, silver, terracotta, with many variants, all across the Roman empire. Pliny describes the Aphrodite as the best work by Praxiteles and the best sculpture in the world, as such visitors travelled to Cnidus especially to see it as a tourist attraction (36.20-21).

Domestic worship extended to gods and goddesses that entered the private realm of Roman domestic contexts for different purposes. Fertility and life expectancy were, for example, of huge concern in the ancient world. Symbols of fertility therefore abounded in the houses and the gardens of many families in Pompeii and Herculaneum, embodied by statues and paintings of the god Priapus, with his large phallus, and of Venus, the goddess of erotic love, sexuality, and fertility. Venus could appear in a variety of ways and attitudes and with a variety of attributes that changed over time and according to type of cult. The naked Venus, represented standing while covering her modesty with her right arm and holding her drapery in the left, was an incredibly popular model in antiquity. Her origin lays in the artwork of the Athenian sculptor Praxiteles (active around 375-330 BC), who produced a sculpture of Aphrodite to be set up in the shrine of the city of Cnidus. From the 2nd century BC, the model became incredibly popular and was replicated endless times: in life-size copies and smaller versions, in marble, bronze, silver, terracotta, with many variants, all across the Roman empire. Pliny describes the Aphrodite as the best work by Praxiteles and the best sculpture in the world, as such visitors travelled to Cnidus especially to see it as a tourist attraction (36.20-21).

But the realm of domestic worship was also quickly infiltrated by numerous gods and deities of foreign origin, such as Attis and Cybele, of Eastern origin, and gods and goddesses of Egyptian origin, as found in numerous houses in Pompeii and Herculaneum. Inhabitants of the Italian peninsula had a long lasting love of Egypt: Egyptian objects and decorative elements are found in Italy from the 7th century BC but it is only from the second half of the second century BC that the passion for Egypt became increasingly widespread across the Italian peninsula. Egyptomania increased with the victory of Augustus against Marc Antony and Cleopatra at Actium in 31 BC and the definitive annexation of Egypt as a province to the Roman empire in 30 BC. This Egyptomania can be seen in numerous wall-paintings and mosaics with landscapes of the Nile and in the adoption of luxury Egyptian furnishing in Roman domestic contexts. During the second half of the first century BC, the cult of Isis and Serapis had become so popular that Augustus ordered a series of restrictions against their worship within the sacred boundaries of Rome in 28 and 21 BC.

Isis was an Egyptian goddess, originally associated with mourning and funerary practices. During the 4th century BC the worship of Isis spread across the Greek world: she was assimilated to the Greek goddess Demeter and could also be associated to Artemis and Aphrodite. The Romans probably got in touch with the cult of Isis thanks to their increasing role in the Eastern Mediterranean. In the 2nd century BC there was a large temple of Isis in the Greek island of Delos, a large Mediterranean trading centre, with a diverse community that included numerous rich Italian merchants. The first temple to Isis was built in Pompeii in 80 BC. The veneration of Isis was a mystery cult and the initiated were sworn to secrecy: we know however from the works of Plutarch and Lucian and from wall-paintings found in Herculaneum that the cult included a process of initiation, including bathing, fasting, receiving a special garment, experiencing and celebrating the revelation of the goddess.

Statues of Isis appeared in various domestic contexts, both referring specifically to Egyptian cults but also among other deities that made up the Penates of a lararium. Here they appeared in the form of Isis-Fortuna (standing, steering a rudder in her right hand and holding a cornucopia with her left arm) or as Isis Lactans (seated on a throne, holding or nursing her son Horus/Harpocrates). The statue of Isis Lactans or Isis Kourotrophe (Inv. 1446/76724) was found in in 1936 at the first floor of shop 5, in the Insula Orientale, II in Herculaneum. The statue is made of terracotta and shows the goddess sitting on a throne while nurturing Horus. It has been dated between the end of the first century BC and the beginning of the first century AD. Her feet, wearing sandals, rest on a foot stool. She wears a short-sleeved chiton (Greek dress) and a mantle that covers her legs. She wears a wide band, adorned with flowers above the temples and crowned by a high diadem on which the two horns of the moon crescent are represented in relief. Harpocrates is sitting on her knees, naked, and wears a band on the head which still bears the remains of the pschent, the pharaonic double crown, now lost. An inscription in Greek bears the name of the artist who made the statuette: Pausania(s) epoiesen.

Statues of Isis appeared in various domestic contexts, both referring specifically to Egyptian cults but also among other deities that made up the Penates of a lararium. Here they appeared in the form of Isis-Fortuna (standing, steering a rudder in her right hand and holding a cornucopia with her left arm) or as Isis Lactans (seated on a throne, holding or nursing her son Horus/Harpocrates). The statue of Isis Lactans or Isis Kourotrophe (Inv. 1446/76724) was found in in 1936 at the first floor of shop 5, in the Insula Orientale, II in Herculaneum. The statue is made of terracotta and shows the goddess sitting on a throne while nurturing Horus. It has been dated between the end of the first century BC and the beginning of the first century AD. Her feet, wearing sandals, rest on a foot stool. She wears a short-sleeved chiton (Greek dress) and a mantle that covers her legs. She wears a wide band, adorned with flowers above the temples and crowned by a high diadem on which the two horns of the moon crescent are represented in relief. Harpocrates is sitting on her knees, naked, and wears a band on the head which still bears the remains of the pschent, the pharaonic double crown, now lost. An inscription in Greek bears the name of the artist who made the statuette: Pausania(s) epoiesen.

Although numerous are the statuettes of Isis (especially in the variant of the Isis-Fortuna) and of Harpocrates found in Herculaneum, the statue of the Isis Lactans is an unicum in the city, as no other statue of the same type (even the Egyptian version) has been found so far (see Bailey, D.M., 2008. Catalogue of the terracottas in the British Museum: Ptolemaic and Roman terracottas from Egypt, vol. 4. British Museum Publications Limited).

The statue is part of one small group of Egyptianizing objects that was found around the so-called "Palaestra" in the Insula Orientalis II of the city. Some of the objects can be clearly related to domestic and private worship, such as the statue of Isis Lactans, together with eight pendants including three made of bronze representing Harpocrates and a wooden sistrum (musical instrument related to the cult of Isis) that were found in the shops that overlooked the main street (cardo V). However, many other objects, including a beautiful basanite statue of the god Autun, dating to end of the 4th-beginning of the 3rd century AD, were found in or nearby the Palaestra, a space that it is suggested could have been a sanctuary of Isis and of the Mater Deum (Mother of the Gods).

References

Barrett C. E., 2017. Recontextualizing Nilotic Scenes: Interactive Landscapes in the Garden of the Casa Dell’Efebo, Pompeii." American Journal of Archaeology 121, 2: 293-332.

Bodel J. e S.M. Olyan (eds.) 2008. Household and Family Religion in Antiquity. The Ancient World: Comparative Histories, Oxford.

Catalano V. 2002. Case, abitanti e culti di Ercolano, Rome.

Catalano, V., 1957. Antiquarium Herculanense. Naples.

De Vos, M., 1980. L'egittomania in pitture e mosaici romano-campani della prima età imperiale: testo italiano di Arnold de Vos (Vol. 84). Brill.

Flower, H. I. 2017. The Dancing Lares and the Serpent in the Garden: Religion at the Roman Street Corner. Princeton University Press.

Gasparini, V., 2010. La “Palaestra” d'Herculanum: un sanctuaire d'Isis et de la" Mater Deum". Pallas: 229-264.

Giacobello, F., 2011. Testimonianze del culto dei Lari dall'area vesuviana: significato e nuove interpretazioni, in Bassani M., Ghedini F. (eds.), Religionem significare. Aspetti storico-religiosi, strutturali, iconografici e materiali dei sacra privata. Atti dell’incontro di studi (Padova, 8-9 giugno 2009). Antenor Quaderni 19, Rome: 79-89.

Krzyszowska A., 2002. Les cultes privés à Pompei, Wroclaw, Université de Wroclaw.

Sofroniew, A. 2016. Household Gods: Private Devotion in Ancient Greece and Rome. Getty Publications.

Torelli M., 2001. La preistoria dei Lares, in Bassani M., Ghedini F. (eds.), Religionem significare. Aspetti storico-religiosi, strutturali, iconografici e materiali dei sacra privata. Atti dell’incontro di studi (Padova, 8-9 giugno 2009). Antenor Quaderni 19, Rome: 41- 55.

Tran, Vincent Tam Tinh, and Yvette Labrecque. Isis lactans: corpus des monuments greco-romains d'Isis allaitant Harpocrate. Vol. 37. Brill, 1973.

van Andringa W. , Quotidien des dieux et des hommes. La vie religieuse dans les cités du Vésuve à l’ époque romaine, Rome, École française de Rome, 2009.

Vinci, M. 2014, Origini e sviluppo dell’iconografia dei Lari: Lari domestici e Lari compitali. Mediterranean Archaeology: 91-98.

Portraits from Herculaneum

With the exception of the portraits from the Villa of the Papyri, more than sixty portraits have been found in Herculaneum since the time of its discovery. Most of them are private portraits and honorary statues but there are also portraits of the emperors and members of the imperial family.

This is the case, for example, with the bust of Livia, a small portrait (36 cm. high) of the empress made from thin silver foil, accurately shaped to represent the features of the wife of Augustus. The portrait comes from the old sea shore of Herculaneum, in proximity to the Area Sacra Suburbana (inv. 4205/79502), where it was probably originally displayed and from where it was displaced by the violence of the volcanic flow that caused the dislocation of most of the portraits found in Herculaneum from their original context. The sculpture was badly damaged by the eruption and the features of Livia are merely recognisable: the thin silver foil used to make the statue did not resist the weight of debris from the Vesuvian eruption. The silver foil was supported inside: fragments of cloth and a small wooden plank were found inside the bust. They were originally meant to support the portrait.

The empress is portrayed wearing a diadem of laurel leaves, with long, wavy locks, parted at the centre of the head, and tied to the back with a band. Two curly locks fall on the shoulders. The diadem of laurel leaves is particularly interesting, as laurel leaves were commonly associated with the celebration of martial virtues and used as male attributes in Roman imperial contexts. So, why is Livia portrayed with such an unusual attribute? The use of the laurel crown as a female attribute is considered an innovation of the Augustan era, as there are no examples of Hellenistic queens wearing a similar attribute. It is likely that the adoption of the laurel in the portrait of Livia had to do with the role that the laurel gained within Augustan ideology: since 27BC Augustus had obtained by the Senate the right to decorate the front of his house on the Palatine with two bay trees, and had gradually taken on himself the right to associate himself with the laurel, by excluding anyone else from triumphal celebrations with the exception of the members of his family. A wood of bay trees also decorated the villa of Livia ad Gallinas Albas, from which the emperor used to take branches while celebrating his triumphs. At the death of Augustus, in AD14, and in the delicate aftermath of the succession of Tiberius to the throne, Livia was bequeathed the posthumous adoption by Augustus, becoming an effective member of the gens Iulia and a descendant of Venus. Livia could then be portrayed wearing a laurel crown, a powerful symbol of her belonging to the gens Iulia and of her role as the mother of the new emperor.

If the bust of Livia reflects notions and ideas about power as reflected in the official context of imperial propaganda, small wooden statues charred by the surge of the Vesuvius reflect the other end of the spectrum but nonetheless can offer an insight into the use of figurative art in domestic and religious contexts.

Because of the fragility of the material with which they were made, wooden statues rarely survived up to modern times. However, we have plenty of literary and documentary evidence that confirm their role in the context of public and private displays across the roman empire. We know for example that wooden statues could be carried across the streets of roman cities during processions and religious events. The portraits of the kings were carried alongside images of the gods during the processions that preceded the ludi and other public spectacles or during religious ceremonies. It is likely that many of these statues were made of wood (if not entirely, at least some body parts): a document from Arsinoe, dating to the Severan age, recalls the costs for paying those who transport wooden statues during a procession in the theatre.

Livy mentions two statues made of cypress wood that were displayed in the temple of Iuno Regina in Rome and that were carried in procession through the Roman Forum and the streets of Rome to end up in the temple of the goddess (Liv. XXVII,37,12). We also know that a cult statue of Veiove made of cypress wood was put 192 BC on the Capitoline hill and that it was still intact at the time of Pliny (N.H. 6.216). The cult statues of Diana Aventina and of the Fortuna Muliebris in Rome were also made of wood (Meiggs 1982, 321-322 and Martin 1987, pp. 20-25.). The fact that wood was perceived as a valuable material for making statues is also suggested by the celebration of its sacrality in the context of Augustan poetry: when Vergil describes the meeting between king Latinus and the Trojans, he sets it in the old palace of Picus Laurentius, alongside a long series of portraits of the ancestors that are carved from cedar wood (effigies avorum e cedro, Verg. Aen. VII.177-178).

One of the most striking examples for the use of wood in roman sculpture is provided by ritual depositions in Gallo-Roman sanctuaries: 300 statues, both male and female, comprising busts, heads, animals and body parts, were found in the sanctuary of Fontes Sequanae near Dijon, dating to the Augustan age. More than 1500 statues dating to the first century AD were also found in the sanctuary of Chamaliers (Clermont-Ferrand). Other finds come from various Gallo-Roman sites, including Luxeuil, Bourbonne-Les-Bains, Saint-Amand. The types of wood employed for making the sculptures are not among the most valuable or the hardiest ones, but those who could be more easily found in the area (mainly oak and beech, but also fir, ash, birch and chestnut).

In Herculaneum, wooden artefacts underwent a process of carbonization, caused by temperatures reaching up to 400 °C during the eruption of the Vesuvius. The carbonization of wooden artefacts caused the survival of a small group of wooden statues. Two of them were found in the south terrace of the Sanctuary of Venus, a religious complex with at least two shrines (A and B) and possibly a third one, and additional rooms attached to the main sanctuary. The remains of the statues (inv. 2157 and 2158) were found in room VI that had a space for cooking. According to Catalano (1957) one is a female statue and the other is a statue of Priapus with a hole in the middle of the body to house the apotropaic phallus. Two small bases for wooden images (scarce remains were found during the excavation) were also found on a podium at the bottom of shrine B.

The best-preserved example of a wooden statue in Herculaneum comes however from a domestic context, the Casa del Graticcio di Legno (III.14.13-15). The Casa a Graticcio di Legno (III.14.13-15) had two floors and was divided into three separate areas: a ground floor apartment with two rooms upstairs (entrance from nr. 14), a shop attached to it (entrance from nr. 15) and a separate, first floor apartment that had an independent access from the road through a steep wooden staircase (entrance from nr. 13). The entrance staircase opened into a landing with a small window that gave light to the space from the courtyard of the ground-floor house. A tall chest partially filled the space. From the landing a narrow corridor connected the remaining spaces of the house, with two rooms that opened onto it and a balcony (maenianum). Two additional rooms opened onto the balcony and a small, windowless room opened into the corridor. Among the artefacts found in the first floor flat there is an inscription: Philad(e)lp(hi)a Cn(aei) Octavi fili(a) on a small base of black marble and the fragment of a large, circular, marble oscillum. Some elements of the original furniture were also found: an earth, placed in the corridor, and a series of beds in three of the rooms. One bed was found in room 3 together with objects belonging to the feminine sphere, such as two perfume bottles, two bronze spindles, a bird water feeder, a golden bead and an onyx. Remains of a bed were also found in room 4, together with a marble table (cartibulum). Room 5 was the largest in the flat and had two beds, one for an adult and one for a child. The wooden female head (inv. 322/75598) was found in this room, together with the wooden pediment of a lararium that was found under one of the beds.

The head has a simple, rather graphic rendering of the facial features, with deeply carved lines for the eyes, the nose and the mouth, and a simple hairstyle, combed in large parallel strands that are gathered to the back in a small bun.

Wooden statues were also found in the lararium of the House of the Menander in Pompeii, where they did not survive but casts of them were taken of the hollows left in the lava. Pollini (2007) suggests that the sculptures from Pompeii portrayed the ancestors of the family and that the wooden sculptures were originally covered with a layer of wax, with modelled facial features. It is difficult to say if the statue found in the Casa a Graticcio di Legno in Herculaneum was indeed a portrait (of which therefore we would miss the details lost in wax) and if it represented an ancestor of the family that lived in the house. We know that the display of the imagines maiorum (portraits of the ancestors) in Roman houses remained the exclusive right of the nobility and the bust from the Casa a Graticcio di Legno was found in one of the rooms of a first-floor flat and not in a space where it would be publicly displayed (like for example the lararium in the peristyle of the House of the Menander in Pompeii). The flat itself was not the property of a rich, aristocratic family: its position, lack of elaborate decoration and absence of large reception rooms make it likely that it was inhabited by a family of modest income, if not by people that separately rented its rooms. It is however likely that the statue was kept as an object whose value was determined by its function and meaning, which are unfortunately now lost.

References

Antico Gallina, M., Castelletti, L., Mottella, S., Legrottaglie, G., Azuma, M. and Antonini, A., 2011. Archeologia del legno. Uso, tecnologia, continuità in una ricerca pluridisciplinare (pp. 1-355). EDUCatt.

Ascione, G.C. and Pagano, M., 2000. L'Antiquarium di Ercolano. Electa Napoli.

Borriello, M. (2008). Gentes. Ritratti romani di Ercolano. Guidobaldi, M. P. (ed.). Ercolano: tre secoli di scoperte. Milan, 81-85

Budetta, T. and Pagano, M., 1988. Ercolano: legni e piccoli bronzi. CETSS.

De Carolis, E., 1998. I legni carbonizzati di Ercolano: storia delle scoperte e problematiche conservative, Archeologia, uomo e territorio, 17: 43-57

De Carolis, E., 2007. Il mobile a Pompei ed Ercolano: letti, tavoli, sedie e armadi: contributo alla tipologia dei mobili della prima età imperiale (No. 151). Rome: Bretschneider.

Drerup, H. 1980 “Totenmaske und Ahnenbild bei den Römern.” Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Römische Abteilung 87: 81–129.

Flory, M. B. (1995). The symbolism of laurel in cameo portraits of Livia. Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, 40, 43-68.

Flower, H.I., 1996. Ancestor masks and aristocratic power in Roman culture. Oxford University Press.

Gagetti, E. (2016). La Turchese Marborough: una gemma problematica. Slavazzi, F., Torre, C. (eds.). Intorno a Tiberio 1. Archeologia, cultura e letteratura del Principe e della sua epoca (Vol. 2). Florence, 29-45.

Maiuri, A. (1958). Ercolano: i nuovi scavi (1927-1958) (Vol. 1). Istituto poligrafico dello Stato, Libreria della Stato: 407-420.

Pollini, J., 2007. Ritualizing death in Republican Rome: memory, religion, class struggle, and the wax ancestral mask tradition’s origin and influence on veristic portraiture. Performing Death. Social Analyses of Funerary Traditions in the Ancient Near East and Mediterranean, pp.237-285.

Sena Chiesa, G. (2004). L’alloro di Livia. Studi di archeologia in onore di Gustavo Traversari.II, Rome, 791-8

(1).jpg)