House of the Cryptoporticus, Pompeii

Banner Images: Parco Archeologico di Pompei in the shadow of Versuvius; Dr Thea Ravasi in The House of the Cryptoporticus, Pompeii; view inside the House of the Cryptoporticus with remnants of Roman Wall painting and stucco work; elaborate wall paintings in the House of the Cryptoporticus Bathroom; view towards the rear entrance of the House of the Cryptoporticus; surviving marble Venus figure from the Parco Archeologico di Pompei collection; amphoras in the House of the Cryptoporticus.

Expanded Interiors is developing a site-specific installation for the House of the Cryptoporticus (CdC) in response to its unique structure, decoration, and rich history.

The house was originally excavated under the direction of Vittorio Spinazzola between 1911 and 1919, and under Amedeo Maiuri between 1927-1929. It features a large underground passageway (cryptoporticus) and a small bath complex, both of which are rare features in Pompeian houses. They are decorated with recently restored exquisite Second Style Roman wall paintings that have distinctive designs: an unfolding frieze as part of a sequence of panels and herms in the cryptoporticus, and complex architectural designs that shape illusionistically the walls of the baths. These extraordinary spaces and wall paintings allow Expanded Interiors to explore a variety of artistic strategies of the Roman painters, and to respond with site-specific installations, that will incorporate replicas of Roman objects.

The installation at the House of the Cryptoporticus in Pompeii also complements the Expanded Interiors installation at the House of the Beautiful Courtyard in Herculaneum. Both houses have distinctive spaces, that have strongly contrasting physical qualities and specific private/public functions. They are adorned with particular types of wall paintings, and will allow for the development of different, yet connected contemporary fine-art installations.

The house

Located in one of the busiest areas of Pompeii along via dell’Abbondanza, and not too far from the Forum, the House of the Cryptoporticus was discovered in the early Twentieth century. Excavations of the house were initially carried out under the direction of Vittorio Spinazzola between 1911 and 1919, and completed by Amedeo Maiuri in 1927-1929.

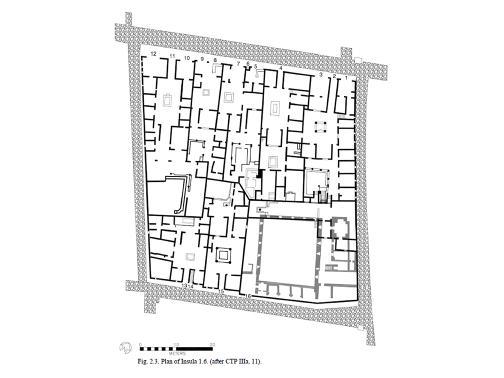

The House of the Cryptoporticus has a long and complex history that spans over more than three centuries. The house was part of Regio I, a popular area of Pompeii with houses, shops, a few workshops, and a small number of rich residences, such as the House of the Citharist, the House of the Menander and the House of the Cryptoporticus.

In the late 2nd century BC, the house, originally independent, became part of a much larger property that included the nearby Casa del Saccello Iliaco. The new property boasted a garden at the back, with a three-sided portico at ground level. During the years 40-30 BC the level of the garden was raised and the porticoes were transformed into a cryptoporticus, with the main entrance at the back of the house. A small bath complex and a large oecus, probably used as a dining hall, were added to the eastern side of the cryptoporticus. The house, the cryptoporticus the bath complex and the oecus were decorated with beautiful Second Style paintings. After the earthquake of AD 62, the two houses were divided again. A big triclinium was then created on top of the northern side of the cryptoporticus and the cryptoporticus itself was transformed into a cellar and partially interred. The east and west corridors of the cryptoporticus were walled up. Unfinished Fourth Style paintings in the Casa del Saccello Iliaco point to an interruption of the re-decoration works of the house at some point, although it is debated whether the brake took place after the earthquake in AD 62, or because of the eruption in AD 79.

Image: Spinazzola 1953

The Cryptoporticus

Cryptoporticoes (covered corridors and passageways) were a common feature of Roman luxury villas, providing villa owners with fresh and cool spaces for leisure and entertainment, much appreciated especially in hot Mediterranean summers. Cryptoporticoes were however rare features in Roman townhouses, and have been found only in a handful of residences in Pompeii and Herculaneum. The addition of a cryptoporticus to the House of the Cryptoporticus conferred therefore an elite status to a property that was set amongst some of the largest and richest houses of Regio I, such as the House of the Menander and the House of the Citharist.

Remarkably well preserved Second Style paintings still adorn the walls of the cryptoporticus and of the surrounding rooms. Created around 40-30 BC, as part of the renovation works carried out in the now unified House of the Cryptoporticus and the House of the Trojan Shrine, the cryptoporticus provided a nice, fresh and shaded space for daily walks for the people of the house and their guests. The main access to the space was probably from the back door of the House of the Cryptoporticus, in Vicolo del Menandro, where a porter controlled the access to the house from a room located next to the entrance. Another staircased passageway, placed next to the baths, provided an access to the underground spaces from the house. Wide clerestory windows were placed on top of the inner walls of the cryptoporticus, allowing corridors to get enough light during the day while leaving the heat outside.

The walls of the cryptoporticus were decorated with Second Style paintings. A sequence of painted herms placed on top of narrow pillars gave a regular rhythm to the decoration that matched the function of the corridors as walking spaces. However, interestingly, the spacing of the herms was not regular, but adapted instead to the spacing of the clerestory windows, creating larger and narrower intervals. Moreover, the positioning of the herms on both sides of the corridor was not symmetrical, conferring dynamism and movement to the decorative space.

The wall at the back of the herms was divided into a sequence of panels, with a meander motif at the bottom, painted in perspective, and a series of horizontal bands at the top. Together with the meander and the 3D rendering of the pillars below the herms, green garlands placed between the herms as if holding from the back of the pillars, provided the walls with a sense of space and three-dimensionality.

A frieze ran on top of the wall, right behind the heads of the herms. The frieze was divided into individual panels, depicting scenes from the Iliad and from the Aethiopis, subjects that were deemed appropriate for walking spaces (Vitruvius, De architectura 7.5.1-2). Much less known today than the Iliad, the Aethiopis was ascribed to the Greek poet Arctinus of Miletus. Its story followed on the Iliad and narrated the events until the death of Achilles and the funeral games held in his honour.

The cryptoporticus was transformed into a cellar during the first century AD. The east and the west wings were walled up and many panels of the Epic Cyclic were damaged. After its discovery, it was severely damaged by the allied bombing of Pompeii in 1945 and some of the still surviving panels of the epic cycle were irremediably lost. Luckily, they had been already recorded and photographed. The surviving frescoes are still visible in situ and have been recently restored.

Image: Spinazzola 1953

The wall paintings

Among the most striking features of the House of the Cryptoporticus, frescoes helped fulfilling a variety of purposes, not only providing a nice and colourful backdrop to daily activities, but also responding to specific notions and beliefs of the house owner and of the wider Pompeian society.

A variety of reasons could determine the choice of themes and subjects in the decoration of a Roman house: dimensions, position and function of a room could have a role in determining its decoration, as well as ideas about decus (appropriateness), status and personal identity. It is not surprising therefore that rooms with distinct functions are decorated in different ways. In the House of the Cryptoporticus , for example, a paratactic scheme was adopted in the walking spaces of the cryptoporticus, while large panels with mythological scenes placed in front of the dining couches were deemed more appropriate to stimulate discussions among guests in the oecus. In the baths, a richer, and more complex design was adopted in the frigidarium compared to the bath’s changing room, establishing a decorative hierarchy that matched the functional hierarchy between the two spaces.

Themes and subjects were also carefully chosen, according to the owner’s taste and beliefs. The celebration of heroic values such as strength, virtus and pietas was deemed appropriate for some of the most important (and possibly more public) spaces of the house: scenes from the Iliad and from the Aethiopis decorated the walls of the cryptoporticus, celebrating the value of Greek and Trojan heroes, such Achilles, Ajax, Diomedes and Hector. The epic cycle developed along the walls in a circular way: entering the room, visitors began a visual journey, beginning with the opening scene of the Iliad displayed on the top left of the wall: Apollo sending a pestilence to the Achaeans for not respecting his priest Chryses. Visitors then followed the story of Troy along the three sides of the cryptoporticus, to come back to the same entranceway. Here, a fresco representing Aeneas fleeing Troy with his father Anchises and his son Ascanius hinted to the future of Rome, according to a widespread Roman myth that celebrated Aeneas as the progenitor of the Roman people.

Placed on the east side of the cryptoporticus, the baths were lavishly decorated with Second Style paintings and colourful mosaics. Baths in Pompeii were a very rare feature of private houses: out of around 400 excavated houses in Pompeii, only 35 had bath suites. Unfortunately, due to the complex and long history of the House of the Cryptoporticus only a few rooms of the baths were still covered by frescoes at the time of its discovery: what was probably a changing room and the frigidarium (cold room). Both rooms were decorated with complex architectural compositions that created a rich three-dimensional effect on the walls by skilfully using architectural perspective, alternating open and closed surfaces, and by breaking up the wall into an endless series of vistas.

The complex of underground spaces was completed at the south-eastern corner of the cryptoporticus by an oecus that was probably used as a dining hall. Its long and back walls were decorated with a paratactic scheme of caryatids on top of which stood a series of panels (pinakes), framed by folded wooden shutters. Convenors to the banquets could recline on the couches and look at the short wall in front of them. Here two mythological panels, one with the scene of Oedipus meeting his father Laios (a scene that clearly preluded to the killing of Laios by Oedipus) and the other with the killing of the Niobids by Apollo, flanked a central panel decorated with what was probably an idyllic scene.

One could wonder why such gruesome scenes were considered appropriate for a banquet hall. Both myths were linked to the story of Thebes, each depicting a story from the mythic cycle of events of that city (Niobe was queen of Thebes and Laios was king of the city). They both represented the story of innocent people, challenged and punished by the gods. Both stories, however, are better understood if we look at the overall decoration of the underground spaces of the house: the paintings of the oecus and of the cryptoporticus celebrate the tragedy of two cities, Troy and Thebes. At the same time, however, there is an underlying Apollinian theme that develops across this whole underground sector of the house. From the entranceway to the cryptoporticus, where Apollo is represented punishing the Achaeans for their hubrys, to the recurrent Apollinian themes in the baths (expressed in more symbolic ways by the Delphic tripod, the sphynxes and the baetylus) to the more complex representations of myths that celebrated the power of Apollo, the avenger of his mother Leto (in the killing of the Niobids) and the god who presides over human destiny (when he met Laios, Oedipus was returning from Delphi, where he had heard by the oracle that he was going to kill his father).

Objects found in the house

A variety of objects were found in the House of the Cryptoporticus and their original find-spot has luckily been recorded by the excavators. Most of the objects refer to the latest phase of life of the house that immediately preceded its destruction in AD 79.

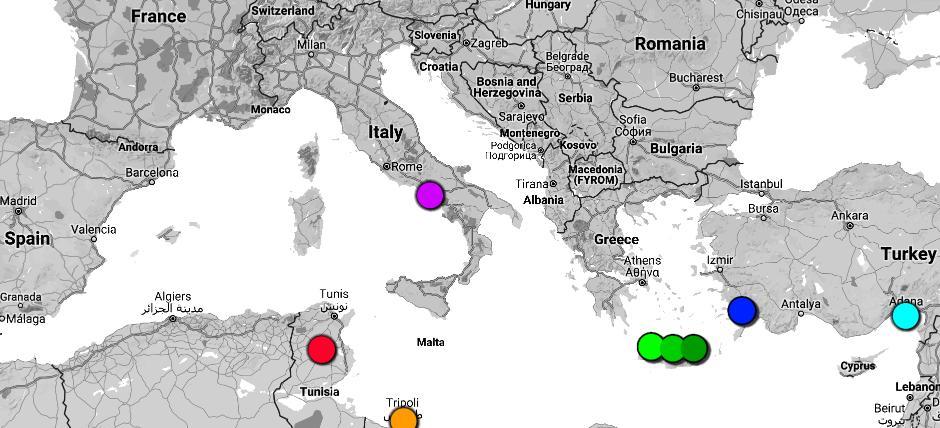

Aside from cooking and serving pots, silver ware and lamps found scattered around the many rooms of the southern part of the house, numerous amphoras were found in the northern corridor of the cryptoporticus, that in the latest phase of life of the house was probably used as a cellar. The amphoras give an insight into the nature of Pompeian trade and exchange, but also into the types of foods that could be found in a Pompeian household in the times that preceded the eruption of the Vesuvius. Goods in the House of the Cryptoporticus seem to have come from Italy but also from regions further away, such as Libya, Tunisia, Greece and Turkey. Aside from wine and olive oil, the now lost painted inscriptions on the amphoras recorded other kinds of food, such as hand-picked olives, spelt flour and lomentum.

Other objects refer more personally to the people who lived in the house, and some were found on the bodies of the people that were unfortunately caught by the eruption while trying to escape from the building, such as jewellery, coins and a key.

Figure 1 – Map showing the provenance of the amphoras found in the Casa del Criptoportico in Pompeii.

Objects were not only part of the daily life activities of the inhabitants of the house: they were also used as beautiful and meaningful additions to the decoration of its walls and floors: a small statue of a sphinx decorated the entranceway to the bath complex, where a colourful mat was recreated as a mosaic on the floor; beautifully painted candelabra flanked the water basin of the frigidarium and a series of still-life paintings decorated the pinakes on top of the walls in the oecus.

Pompeii

The city of Pompeii was established in the 6th century BC near the Bay of Naples in Italy. Occupied by the Samnites during the 4th century BC, it became a major centre of the region during the 3rd and the 2nd century BC, boasting amenities such as a theatre, a palaestra, and a public bath. At this time, many of Pompeii’s leading families lived in huge houses, luxuriously decorated with beautiful mosaics and colourful frescoes. The city came under the control of Rome following the Social Wars, becoming a Roman colony in 80 BC. In AD 62, the city was devastated by an earthquake, which caused the town to collapse. In AD 79, when the city was buried by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, many houses were unoccupied or under reconstruction, and not all public buildings had been completely restored.

After the eruption, the city was lost for over 1500 years. Rediscovered in 1748, the city underwent a systematic plunder of its artworks carried out under the Bourbons that at the time ruled in Southern Italy.

The city soon became an indispensable stop for those who visited Italy during the Eighteen and the Nineteen centuries as part of their Grand Tour. After the unification of Italy in 1861, a new vigour was given to the excavation of the site, this time with the aim of preserving the city and its finds thanks to the progress made by the archaeological research of the time. Today two thirds of the city remain uncovered and restoration projects continue to preserve the unique examples of domestic and public objects, art and architecture that have been revealed.

(1).jpg)