Blog & Podcasts

Pompeii: context and creativity

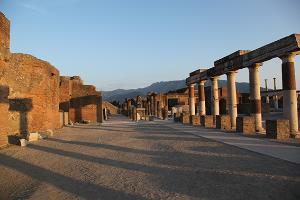

What a pleasure it is to be back in Pompeii. Far from being frozen in time, the city has changed significantly since my last visit. The fruits of the Great Pompeii Project can be seen everywhere. I will write more about this magnificent undertaking later, but for the moment I am just thrilled to see how the expert team behind it have made Pompeii more open and more secure for tourists and specialists alike.

Even after several decades working on the artefacts of daily life in the Roman world, it is impossible not to feel a sense of intense privilege entering the storerooms at Pompeii. This an area few people get to see. The state of preservation of many of the objects here is remarkable, as is the sheer volume of material. At one level it is the rich assemblage of the everyday life that impresses, at another it is the encounter with the quality of individual pieces – to this archaeologist it is as exciting to see multiple examples of near identical bronze cooking pots, as it is to see some of the spectacular decorative work that adorned the homes. I am not ashamed to admit to being delighted. Accompanied by the excellent Mimmo, we were able to scan and photograph key items for the project.

Our Expanded Interiors Project presents its own challenges. My colleague Catrin Huber’s vision is an exciting one, which has at its heart the desire to consider what the study of the Pompeii and Herculaneum can contribute to contemporary art practice. As the archaeological co-investigator, my role is to advise on both the archaeological and the digital documentation strategies. Central to archaeological practice is a sensitivity to context. Analysis of an object requires an appreciation of its dynamic relationship with the society that makes it and, no less crucially, the society which it helps make. To an archaeologist to deprive an object of its context is to rob it of that dynamism and impoverish our understanding.

The issue of context appears to have added potency at Pompeii and Herculaneum. Popular imagination, and indeed a certain amount of archaeological wishful thinking, have tended to assume that objects such as those in the storeroom, left neglected in a moment of awful catastrophe, stood testifying to their everyday context in AD 79. The common belief is that they were found where they were used, in association with the objects that accompanied in the routines of daily life. In reality of course, it is often not so simple, site formation processes seldom are, and anyway, the precise positions of objects were often not recorded by later antiquarians and archaeologists. But the desire to think about context, to think about how individual objects related to the buildings of these cities remains strong. So too, does the wish to examine, to emphasise the best preserved of each object type we encounter. For colleagues in Fine Art, I realise, context matters too, but more in embracing the malleability of context to deliver an experience rather than necessarily in our dissection of it to see how it operated in the past. There are of course meeting points, for archaeologists and creative artists alike, interaction with an object – something that itself removes that object from its archaeological context, is integral to its appreciation too. Both detailed technical study and the creative process Catrin advances, testing each piece’s attributes by reimaging its size, dimensions and composition, reveal the qualities of material culture in different ways. As for preservation, I note that as Catrin makes her selection of the objects from which she will draw inspiration, it is sometimes those which wear the scars of Vesuvian devastation most prominently that catch her eye.

We all speak a lot about interdisciplinarity, and to an archaeologist it is a natural way of working, but this is my first time engaged with the creative process of a leading Fine Artist. As the selection is being made, I find the creative tension challenging – I want to prioritise different strands, different objects, but this is her project, her vision and I trust her. And trust can be key ingredient to helping us look at things differently, not instead of, but as well as. Objects don’t lose their dynamism just because they have been buried for two millennia, Expanded Interiors will be part of their story too. I look forward to seeing where these choices will take her. On a technical level I am happy too, for I have spent more time studying the detail of this remarkable collection – a privilege indeed.

Professor Ian Haynes

Last modified: Thu, 23 Nov 2017 18:12:50 GMT

(1).jpg)