Reflections and emerging results - Dunja Fehimovic

Reflections and emerging results of the first trip to Adjuntas - Dunja Fehimović

15 January 2025

After months - even years - of intermittent conversations and virtual meetings with Casa Pueblo - I arrived in Adjuntas on Tuesday 17 December to finally begin a project that aims to investigate, through practice-based methodologies, the role of community cinema in ecological and decolonial struggles. With my collaborator, Cecilia Sosa, we envisioned this first trip as an opportunity to get to know the town, to introduce ourselves to the community, and to begin to understand how the two axes of the project – ecology and coloniality – are lived in the context of Adjuntas. We set out to achieve this primarily through a workshop entitled ‘Juntxs por Adjuntas’, which took place at Casa Pueblo on 19 and 20 December. What ended up happening on the trip and in the workshop left me with a more nuanced but also less clear idea of the terms ecology, coloniality, film, and community. To follow a cliché of fieldwork writing, nothing really went as expected or planned. A series of difficult, awkward, uncomfortable, breath-taking, beautiful, and all very revealing situations ensued.

It started immediately, with the loss of Ceci's suitcase, which we eventually learned arrived on a flight the next day, but which did not reach us in Adjuntas until two days before our departure, and finally arrived thanks to the intervention of a collaborating filmmaker who was travelling from San Juan to Adjuntas, and who ended up being in many ways our saviour. The lack of a suitcase forced us to start the trip with a visit to a mall in Carolina, where we experienced first-hand what we already knew in theory about the high cost of living in Puerto Rico, and the imposed dependence on imported products. Personally, I was also struck by the absurdity of the (expensive) hats, scarves, and coats with snowflake motifs, clashing with the temperature of over 30 degrees Celsius that had us sweating before we entered the air-conditioned shop. Crossing the car park from Walmart to Old Navy, we also saw the first cinema of the trip - a Caribbean Cinemas that was perfectly in tune with the super-stores surrounding it. I remembered what several Puerto Rican filmmakers had told me about the importance - practically a monopoly - of this international chain, and the difficulties for local films to obtain national and regional distribution and promotion. Watching a woman carry huge bottles of water to her car in the middle of the asphalt baked by the Caribbean sun and surrounded by transnational and mostly US-owned chains, I definitely felt that I was face to face with one side of the ecology-coloniality binomial. We were far from the green imaginaries that the word ‘ecology’ usually conjures up, but even so - or perhaps for that very reason – the situation gave me a glimpse of the difficult, displaced, and uncomfortable relations between human and non-human nature in the Puerto Rico of 2024.

But during the trip, a trend or motif became apparent: the coexistence of hostile elements, which seemed to make life on the island difficult – sometimes to the point of seeming to want to rid it of Puerto Ricans altogether – with the creativity, determination, and necessarily collaborative, communal effort to remain and build a decent, dignified life in the archipelago. Two more images come to mind. Interestingly, they have one element in common: plastic water bottles. On the one hand, these everyday objects recall the privatisation of natural resources, a counterpart to the failure of basic public services in a context marked by colonial ‘public’ debt and consecutive waves of austerity. On the other hand, they also speak to the fragility of living conditions associated with an economic and political but also ‘natural’ context battered by successive hurricanes, earthquakes, and storms. For those familiar with Puerto Rico's recent history, the water bottles cannot help but recall the painful discoveries of warehouses and containers full of expired and undistributed supplies for victims of Hurricane Maria. This scandal exposed the failures of current disaster response models and short-term solutions that tend to reinforce dependency, and contributed to what came to be called ‘el verano combativo’ [the combative summer] of 2019, when a series of mass protests led to the resignation of then-governor Ricky Rosselló.

On the other hand, and especially in the contexts in which we encountered them, the plastic water bottles represent the warmth and openness with which people are received in Puerto Rico. First, the tiny bottles with which we were greeted at the Casa Comunitaria de Medios, where we stopped along the way to Adjuntas to meet colleagues whose work I have followed with admiration for several years. It was a relief to enter the air-conditioned space they had built with their own, collective effort in a huge, formerly abandoned building in the historic centre of Aguirre, a town shaped by the impact of the sugar mill that was later replaced by the polluting shadows of the AES coal plant and the thermoelectric plant. From there, the colleagues of the Casa Comunitaria de Medios contribute to the documentation not so much or not only of ecological/political disasters and ‘slow violence’ but also of the community struggles for another kind of development: local, humane, ecological in the broadest sense of the word. Moreover, in the creative activity itself, they both enact and evidence this ‘other’ way of being and living together. We sat together talking about their projects, about the current state of Puerto Rico, their connection with the Caribbean and Latin America... In short, many things, until we realised that several hours had passed (another recurring theme: the apparent malleability of time lived between meetings and outings on the island). Before finally leaving for Adjuntas, we visited another colleague from the Casa Comunitaria de Medios at the art school where he works, where we witnessed, purely by chance, the joy of a Christmas celebration marking the end of the semester. In a context marked by the closure of public schools – not only due because the cuts imposed by the Financial Oversight and Management Board but is also both a cause and effect of a massive wave of emigration that peaked after Hurricane Maria – the radical affection and effort to foster the creative and expressive powers of the youngest Puerto Ricans have stayed with me as a particularly moving experience.

Although we laughed, remembering our English winters, when people talked about 'la tierra del frío’ [‘the land of the cold'], it is true that coming from the Carolina mall and the relentless sun of Salinas, Adjuntas seemed like another world. This separation seemed to be confirmed by the fact that, despite its promise, the airline never managed to send the suitcase from San Juan to the distant and apparently unknown interior town. Of course, this was also complicated by the fact that we had registered the address of Casa Pueblo, which, despite being a real physical space with office hours (8 to 15h), is actually much more than that: an infinite activity, a constant coming and going, an incessant parade of people not only from all over Puerto Rico but from all over the world, an energy overflowing in multiple directions, creating all kinds of projects and leaving its traces and impact all around. We were not sure if the suitcase would actually make it into someone's hands amid so much unstructured affective activity, so we took the opportunity to introduce ourselves to everyone we met in the surrounding local businesses and tell them what to do if they eventually saw what we imagined as 'an Iberia truck' pulling up... Thus, the privilege of being based at Casa Pueblo also highlighted, for me, the elusive nature of Adjuntas. Adjuntas is the town, but it’s also much more than that. It is an entire municipality composed of very diverse and dispersed communities. What I discovered of Adjuntas, I did afflicted by the nerves of a new driver, winding my way cautiously along the narrow and dizzying mountain roads in a rented car during torrential afternoon rains, and the sudden sunsets that left us without warning in absolute darkness.

And so we come to the second memory marked by bottles of water. Taking advantage of a few quiet, dry morning hours, Ceci and I set out to visit the famous Casa Pueblo Forest School. Guided by the GPS and noting what our colleagues at Casa Pueblo had told us about the existence of a parking lot next to the entrance, we slowly made our way up the mountain. When we suddenly came across the sign announcing the 'Ariel Massol Deyá Forest School,' we continued upwards, unable to see where we were supposed to leave the car along these narrow tracks. We started to enter a path and, upon noticing the sign warning us to 'Beware of the dog,' we quickly backed out. In the end, we concluded that we had to go down a rough and narrow path to the left of the sign, thinking the parking lot would be right next to the entrance. Halfway down, with the rocks scraping the chassis, we parked the Toyota Corolla naively rented at San Juan airport to visit that wonderful place that is the Forest School, leaving the problem of how we would get out of that predicament for later. Upon returning, we realized it would be impossible to reverse up the hill. I began to despair, and to top it off, we saw that there was no phone signal to call for help. We walked to the entrance of this unfortunate path, trying to get some bars. As we passed, we saw a small clearing in front of a sign that said 'private property' – which we deduced must be the mysterious parking lot. After a few extremely tense moments when all the dogs from the surrounding houses came out to 'greet' us, we saw a neighbour coming down the hill. He was carrying two bottles of water in his hands and saying: 'Ceci? Dunja?'

It seems hard to believe, but he had deduced who we were by hearing us in an interview we had given about the workshop for Radio Casa Pueblo. The neighbour, who, although not born in Adjuntas, has lived there almost all his life, told us that he hardly ever left the house because he didn't want to leave his mother alone – a woman who, at over 90 years old, seemed the most lucid of all of us! Despite their apparent physical isolation, they keep up to date about the goings on of the town and the entire municipality by listening to Puerto Rico’s first community and ecological radio station. There could be no better testament of the importance of this local institution in weaving the imagined community of Adjuntas. And this family – which also includes a brother who returned to Adjuntas after living in the United States for many years, and who ended up getting our car out alongside exclamations (in English) of 'Oh my God! Why did you do that? Never do that again!' – also told us something about the particular combination of connection and disconnection, of the hyperlocal and the transnational, that seems to characterize life in Adjuntas. Both shaken and moved by the adventure, we returned to the town, where we had the privilege of being welcomed to the late Tinti’s house by Alexis Massol. The literal and metaphorical weavings of that great woman, Faustina Deyá Díaz, laid the foundations and continue to ensure the functioning of Casa Pueblo as a community project characterized by affective work, and family, community, and patriotic ties. In her house, I was able to appreciate some traces of an life incredibly rich in friendships, family, travels, experiences, readings, and struggles.

Juntxs for Adjuntas Workshop

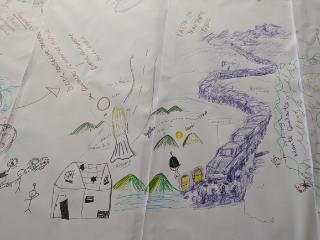

All this, and more than can ever be written in a blog entry, influenced the way I experienced and understood the events of the workshop, which have helped us to outline – together with the participants – several thematic threads that we will develop in a participatory documentary focused on Adjuntas and the thematic axes of the project. For me, these threads combine to articulate a concrete but very open subject matter that will allow participants to follow their interests: the effort to establish and maintain a relationship with the human and non-human environment – that is, the effort to build ecology in the broadest sense of the word – in a contemporary context marked by different manifestations of coloniality and climate change.

- Oral History: Several participants spoke of the desire to capture and record the stories of their relatives, their memories of the town and beyond, reflecting the aging of the local population especially but also throughout Puerto Rico, given emigration and the living conditions that make it difficult to have a family. We understand this theme as the expression of a desire to maintain the bond with the town, the land, the local culture and history, by building or maintaining intergenerational ties.

- Gentrification: We discussed the impact of two elements of the legislative, economic, federal infrastructure: on the one hand, Puerto Rico Incentives Code 60, which offers tax exemptions and encourages U.S. citizens to become residents of Puerto Rico. This legislation has encouraged the purchase of houses and land first in metropolitan areas and then in other parts of the archipelago, raising prices, making it difficult to return to or continue living in municipalities like Adjuntas, depopulating the mountains and repopulating them with Airbnbs. On the other hand, the so-called Home Repair, Reconstruction, or Relocation (R3) program, which seeks to provide three types of assistance to those in homes deemed uninhabitable after hurricanes Irma and Maria. Within Adjuntas, this assistance has often been experienced as an attempt to evict people from strategic locations, offering them in return a sum of money that does not replace the fiscal value, much less the emotional value of their homes.

- Forms of Resistance: In response to, or despite these pressures and difficulties, during the workshop and outside of it, we learned of forms of resistance by individuals and groups who insist on building a life in the mountains (and beyond). As a counterpart to the closure of schools, practically every self-management initiative seems to flourish in a ‘rescued’ or recovered space, which is used to provide basic services and cultural and community activities that are – I would say - equally necessary to imagining a sustainable life and a livable world in the current context of Puerto Rico. Solar panels, facilitating simpler, off-grid ways of life, in greater harmony with the natural environment. Agroecological projects and artisanal processes, which demonstrate and put into practice a radical love for the land and the possibility of living off it.

- Connection-Disconnection: This paradoxical pairing was abruptly imposed on us during the first night of the workshop, making it impossible not only to carry out what we had imagined as a short filming exercise using mobile phones but also any type of dialogue. What we had just experienced was a caravan – in this case, the Christmas caravan. For those unfamiliar with this cultural phenomenon, the caravan is a long parade of cars, motorcycles, and trucks, with sirens and horns all blasting at full volume, that pass slowly through the town to mark an important event. As a popular cultural practice, it represents and fosters a kind of connection, but it also cuts off the circulation of traffic and imposes an almost unimaginable level of noise. Other aspects of car culture were discussed; the roads that are so important in a rural context without public transportation, the high price of cars, the proliferation of tolls and traffic jams. All combine connection with disconnection. Many of the other phenomena and images we talked about can also be understood within this paradoxical pairing.

- Imaginaries of Adjuntas: It was impossible to escape the Sleeping Giant, this iconic and, for some, clichéd figure, whose silhouette can be made out in the mountains from the town of Adjuntas. But other local stories and legends were also discussed: the 35 walls that one can count along a road leading out of the town to see the ghost of a local woman who committed suicide, and La Madama, the beautiful woman murdered by her jealous husband while hanging clothes to dry. Local creative interventions were also very present, such as the murals that several artists were finishing in the Plaza de la Independencia Energética [Square of Energy Independence], in those days before its inauguration. Some of these interventions draw inspiration from the natural world, using butterflies, snakes, and endemic birds to think about the challenges and joys of life in Adjuntas, and Puerto Rico in general. Others configure the local from a perspective that recognizes Puerto Rico's colonial condition but also affirms its position within a globalized world.

What I learned in these two nights of the workshop I owe to the intelligence and creativity of the participants. The people who participated in the activity, and with whom we talked during the trip, shared so much with us, and I am excited about the possibility of continuing to collaborate with them. However, the way I understand participation has changed; I now realize that it is a constant process and negotiation. In the coming months, we will be working together to film different events, interviews, images, and sounds linked to the threads described above. We will continue to think of ways to open the process up to the participation of more people, and to different types of participation. With this spirit in mind, we set up a board during Casa Pueblo’s Fiesta del Sol on December 21, inviting people to leave us their suggestions for locations, figures, sounds, and images to include in a documentary about Adjuntas, or in a documentary about ecology and coloniality. I think we will be able to incorporate many of those suggestions. Let this blog entry serve as a new call for participation: if you have any questions, comments, or want to take part in any element of the process, please do not hesitate to contact me: Dunja.Fehimovic@newcastle.ac.uk. See you again in Adjuntas from February 2 to 14!