Panamanian cinema - Luis Lorenzo-Trujillo

The (not so) Brief History of Panamanian Cinema

18 July 2025

-700x349.png)

Still from Al calor de mi bohío [In the Warmth of My Hut] (Carlos Luis Nieto, 1941)

A wise old man taught me that, if the history of cinema is more than a century old, the history of Panamanian cinema has a much shorter trajectory. That is why it is unfair to compare our cinematography with that of countries with a more consolidated tradition.

I do not present this as a preemptive excuse, but because that same person is one of the authors of the only book on the history of Panamanian cinema that has been written to date. I am referring to Breve historia del cine panameño (1895-2003) [Brief history of Panamanian Cinema], by Édgar Soberón Torchia and César del Vasto.

At the time of its publication, there was no other way to describe Panamanian cinema but as ‘brief’. Up until that point, our filmography consisted of just five feature films and one medium-length film:

- Cuando muere la ilusión [When Hope Dies], by Carlos Ruiz, Julio Espino, Carlos Ochoa and Rosendo Ochoa (1949)

- El misterio de la pasión [The Mystery of the Passion], by José María Condomines (1954)

- Panamá, tierra mía [Panamá, My Land], by Jorge I. De Castro (1965)

- Ileana, la mujer [Ileana, The Woman], by Jorge I. De Castro (1966)

- Panamá, by Jesús Enrique Guédez (1976)

- El imperio nos visita nuevamente [The Empire Visits Us Again], by Sandra Eleta (1990).

Twenty-two years later, I dare to bracket the ‘(not so much)’ in the title of this text, because, according to the count of Panamanian films that I keep since the research done by Soberón Torchia and Del Vasto, last year we surpassed the hundred feature films mark with the national premiere of Rodrigo Quintero Araúz's Me dicen el Panzer [They Call me Panzer], a biopic of footballer Rommel Fernández (2024).

I find this round figure worth celebrating for several reasons, but above all because it allows me to share an analysis of Panamanian cinema based on a more robust and, above all, vital filmography. For this reason, I am not approaching this study via the archaeological findings of Panamanian cinema, but through one of its most recent films.

-700x377.jpg)

Still from Me dicen El Panzer [They Call Me Panzer] (Rodrigo Quintero Arauz, 2024)

1. HIJO DE TIGRE Y MULA

On 13 March this year, the Panamanian documentary Hijo de tigre y mula [Son of a Tiger and a Mule] was released. Annie Canavaggio's film constructs, from archival material, a benevolent portrait of General Omar Torrijos during the negotiations of the Torrijos-Carter Treaties, a diplomatic agreement between the United States and Panama that guaranteed our country the restoration of sovereignty over the Panama Canal after almost a century of US colonial control.

This film was released shortly after US President Donald Trump made clear his intention to take back the Panama Canal, citing abusive tariffs charged to US ships and an alleged interference of the Chinese government in the operation of the inter-oceanic passage and two ports located in the areas surrounding the crossing.

Canavaggio's film, which was initially scheduled to run for two weeks, was extended to a total of six weeks due to the massive audience response, making it the most successful documentary in Panamanian cinema since Abner Benaim's Invasion, with more than 17,000 viewers. This reception should come as no surprise, as the film has the capacity to fill viewers with self-esteem and patriotic fervour as it recalls how the country achieved its goal of recovering the Panama Canal, despite having all the odds stacked against it from the start.

But what interests me most about Hijo de tigre y mula is not so much its dialogue with the past, but with the present and the future of our nation. On the one hand, after watching the film, one inevitably wonders whether we are prepared to face this new threat from the U.S. On the other hand, Canavaggio's film harbours an epiphany. But before revealing what it is, it is necessary to ask some questions that allow us to reflect on Panamanian cinema and coloniality.

-700x394.jpg)

Still from Hijo de tigre y mula [Son of a Tiger and a Mule] (Annie Canavaggio, 2025)

2. THE BIRTH OF PANAMANIAN CINEMA

The first question I would like to ask in order to think about Panamanian cinema is: When was Panamanian cinema born?

If we turn to the calendar, the answer is simple: 1946.

That year, Carlos Luis Nieto presented Al calor de mi bohío [In the Warmth of My Hut]. This short fiction film, about a teenage girl who moves from the countryside to the city after being impressed by the luxury and glamour of a woman newly arrived from the capital, is considered by historians to be the first Panamanian fiction film. Undoubtedly, it is a first heartbeat, but it was far from endowing our cinema with an identity, as it had neither continuity nor influence on subsequent works made in our country.

For a long time, the Panamanian film guild has pushed the thesis that film from Panama was born in 2009 with the release of Abner Benaim's Chance. The comic story of two maids who rebel against their bosses and kidnap them until they are paid the benefits they are owed became the first national film to have a commercial run in our cinemas. Therein lies the problem with this thesis, as it confuses economic exploitation with a possible cinematic identity.

That is why I propose an intermediate date between 1946 and 2009.

In reviewing the filmography of Panamanian cinema, I discovered that its production accelerated from 1990 onwards, as shown in the list below:

- El imperio nos visita nuevamente [The Empire Visits Us Again] by Sandra Eleta (1990)

- One Dollar by Héctor Herrera (2002)

- La noche [The Night] by Joaquín Carrasquilla (2002)

- Tras las huellas del campeón [In the Footsteps of the Champion] by Amargit Pinzón (2004)

- Marea roja [Red Tide] by Carolina Proaño Wexman (2005)

- Los puños de una nación [The Fists of a Nation] by Pituka Ortega Heilbron (2005)

- Curundú by Ana Endara Mislov (2007)

- Burwa Dii Ebo by the Igar Yala collective (2008)

- Chance by Abner Benaim (2009).

Something happened between 1990 and the formal arrival of democracy in Panama that provoked this growth. The answer is simple, but grim: the US invasion of Panama on 20 December 1989. I propose this date as the true birth of Panamanian cinema. But to explain why I must go back even further in time.

.jpg)

Still from Chance (Abner Benaim, 2009)

3. A DEFINITION (IF POSSIBLE) OF PANAMA AND PANAMANIAN CINEMA

What is Panama?

In essence, Panama is a geological fault line. Three million years ago, tectonic plates collided with each other, dividing the great sea into two: the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

In a way, this geological fault created a cinematic frame that defined the Panamanian territory. Unlike other countries, this frame was not established via a human logic, obsessed with the idea of borders. Rather, this space was suggested by nature itself. And this is no small matter, at least not in filmmaking.

We already have a frame, but a first image or cinematographic gesture is needed to give life to Panamanian cinema. In that sense, we discover that this geological event that happened more than three million years ago, in addition to separating the great sea in two, created a land bridge that we know as the Isthmus of Panama. Since then, this natural bridge has been used by animals, humans and machines to cross from one end of the American continent to the other. They are all passing through, never staying in our country.

This use of the territory has defined the history of Panama and that of its own inhabitants, who understand their identity based on the idea of the Panama Canal and slogans such as ‘Bridge of the world, heart of the universe’ or ‘Pro mundi beneficio’.

Inspired by this logic, I found the gesture I was looking for: a body - be it animal, human or machine - that enters at one end of the frame, crosses it completely and disappears at the opposite end of the composition.

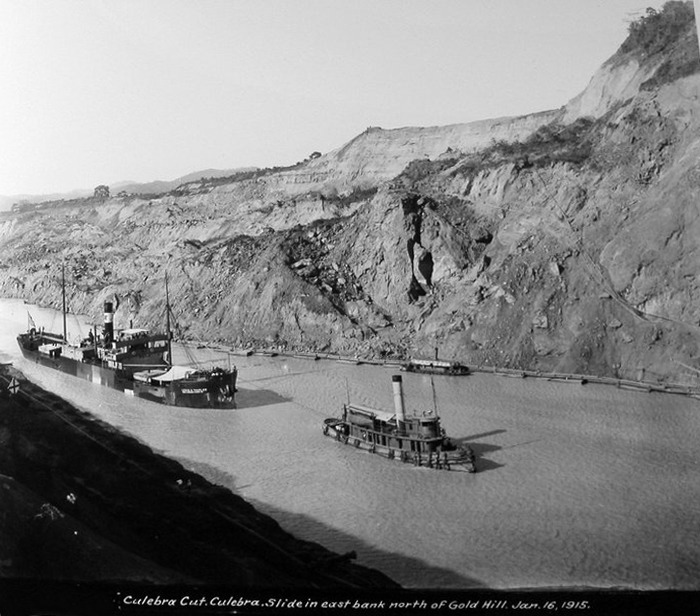

That is why for me the seminal image of Panamanian cinema is that of a boat crossing the locks of the Panama Canal.

Photo by Getty Images

This crossing of the boat across the inter-oceanic canal draws a line that cuts, divides or separates the frame (and, in turn, the territory) in two.

This cut in the territory evokes, in turn, the idea of a wound. According to this hypothesis, the boat is a scalpel and Panama is the tissue on which its blade rests. Every time a ship crosses, it opens a wound through which our territory bleeds and dries up. In fact, it is estimated that every time a ship passes through the current set of locks of the Panama Canal, more than 200 million litres of fresh water are dumped into the sea and never recovered.

The question is: what is lost in this bleeding?

There is a long pictorial tradition of depicting wounds. For example, I think of Rembrandt's ‘The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp’ or Caravaggio's ‘The Unbelief of St. Thomas’. Both works tell us that a cut is needed to tear away the layers of appearances. Only then will our gaze be able to see through them and reach a deeper understanding of reality.

-700x481.jpg)

A section from the painting ‘The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp’ (Rembrandt, 1632)

In the case of Panama, the injury caused by the constant crossing of ships through the Canal is not necessarily bloodshed. It is something else. And I found the answer in the following phrase from William Shakespeare's Hamlet: ‘Time is out of joint’.

This phrase is spoken by the ghost of the King of Denmark to Prince Hamlet, after summoning him to a nocturnal meeting at the outskirts of his kingdom to reveal to him that his death was not the result of natural causes, but of a conspiracy that led to his murder. That crime caused time to unravel.

In a way, the definition I propose of Panamanian cinema has to account for that first cinematographic gesture: the crossing of a ship through the inter-oceanic passage. But also of that wound. That is to say, of the precise moment when Panama's time became out of joint.

That is why the definition I propose of Panamanian cinema does not claim that it was born in 1895 with the arrival of the cinematograph. Much less in 1946, when that first film was presented in public. Nor in 2009, when its commercial exploitation began.

For me, Panamanian cinema was born in 1989 with the Invasion of Panama, since this event reopened the wound of being a country doubly colonised, first by Europe and then by the United States.

This would explain why film production in Panama accelerated from that date onwards. Every birth is, in a way, an emergency. The birth of our filmography was no exception. That is why the title of Sandra Eleta's film, the first Panamanian film to be produced and released after the Invasion, seems so prescient to me: El imperio nos visita nuevamente.

4. WHO ARE PANAMA'S FILMMAKERS?

Let us return, once again, to the image of the ship crossing the Panama Canal. This time not to define Panamanian cinema, but to try to establish who are the filmmakers of Panama.

That boat is a steam engine, which brings to mind another engine powered in the same way: the train. Both methods of transport are symbols of earlier stages of capitalism.

There is a tradition, starting with the Lumière brothers, that links the train with the cinema. There are also theories that argue that without the mechanism of the train, the cinematograph could not exist. The principle of the wheel is, in a way, the principle of the film reel inside the film camera.

This leads me to think about the initial debate surrounding the cinematograph. At first, it was seen as a scientific tool for its ability to record reality. Later, its storytelling potential was discovered and it became a spectacle. For some strange reason, the two possibilities were separated, as if they were irreconcilable, when perhaps they are one and the same. This is why Gilberto Pérez defines cinema as a material ghost. This leads me to think that not enough importance has yet been given to the spiritualistic capacity of the cinematograph to evoke an invisible presence through the phantasmagoric character of image and sound.

Returning to the scene in William Shakespeare's Hamlet, the ghost of the King of Denmark orders his son to solve the crime that resulted in his assassination, in the hope that time will return to its natural course. The ghost's call does not necessarily seek justice or revenge. What he wants is for his son to question and challenge the foundational narrative of his kingdom.

Drawing a parallel, I dare say that if Panamanian cinema is born of the wound opened by the US invasion of Panama, Panamanian filmmakers are those who heed the call of the ghosts that inhabit our territory, seeking to make us question the foundational narrative of our nation-state. A narrative, we must not forget, that has been imposed by the colonising empires after their passage through the Isthmus.

Panama was first visited by Spain, whose campaign of extermination, evangelisation and plunder ensured the commercial exploitation of the inter-oceanic route. At that time, that route was overland and consisted of the Camino Real and the Camino de Cruces. Through them, Europeans transported the gold and silver plundered from our continent, in addition to trading throughout the Americas the Africans they enslaved and exploited as labour.

This use that the white man made of the Isthmus of Panama enabled the arrival of modernity, in addition to laying the first pillars of a capitalist and global system that spread from Central America and the Caribbean to the rest of the world.

Half a century later, Panama received the next visit from Empire. This time it was the United States, which carried out a military operation called ‘Just Cause’ to capture Manuel Antonio Noriega, after the dictator and head of the Panamanian armed forces declared war on the government of President George Bush senior. This visit caused a rupture in Panama's history, which on the one hand allowed the arrival of democracy after more than 30 years of dictatorship. But this process was not independent. On the contrary, it was under the tutelage of the US empire itself, based on negotiations with the country's creole elite. This process diverted us from what should have been our next step after achieving the signing of the Torrijos-Carter treaties on 7 September 1977.

We have already established that this treaty obliged the United States to recognise Panama's sovereignty over the Canal. What I have not yet discussed is that this sovereignty was not complete, since the country of the stars and stripes retained, through a second document called the Treaty of Neutrality, the permanent right to defend the Panama Canal from any threat that might interfere with its operations. This treaty has been invoked by President Donald Trump's administration to justify its current drive to regain control over the Panama Canal.

This is the epiphany captured in Annie Canavaggio's documentary Hijo de tigre y mula, which has the great wisdom of recovering the statement made by General Omar Torrijos at the time of the signing of the Torrijos-Carter Treaties: "Dear President Carter, I want to make it clear to you that this treaty does not enjoy the full support of our people, because military bases remain in place that make my country a possible strategic target for retaliation, and because we are agreeing to a neutrality agreement that places us under the defence umbrella of the Pentagon".

5. SOME REPRESENTATIVE FILMS FROM PANAMA

Seeing and hearing these words on the big screen convinced me that ghosts do exist. At least, in the way Shakespeare's pen invokes them. This revelation allows me to draw a line connecting Panamanian cinema from El imperio nos visita nuevamente (1990) to Hijo de tigre y mula (2025).

From here, it is possible to suggest some films that represent Panamanian cinema, although I must say that the task is not easy. The first Panamanian films are influenced by the 'cine de pecadoras' (sinner films) of Mexico's Golden Age. Another large proportion of our films seek to participate in the Hollywood canon and European auteur cinema, but without the economic muscle that sustains the former or the tradition that nourishes the latter.

This diagnosis perhaps invites us to think that the imaginary of Panamanian cinema is colonised and shaped by the cinema of the countries that have colonised us. Although I sense that this struggle for subjectivity involves an encounter with the real, since most of the films that I propose below are non-fiction. That said, these are some of the representative films I propose from Panama:

_1-700x525.jpg)

Still from El imperio nos visita nuevamente [The Empire Visits Us Again] (Sandra Eleta, 1990)

El imperio nos visita nuevamente [The Empire Visits Us Again] - Sandra Eleta (1990)

This film can be considered as Panamanian cinema's cry of urgency. The first half of the film deals with the arrival of the Spanish empire in Panama through fiction and the legends of the Congolese people of Portobelo. Gradually, through the sound of helicopters, the arrival of the next colonising wave is suggested in the space beyond the frame. The transition is brutal: archival footage shows the destruction of Panama City and Colón by the US army. The director then goes on, camera in hand, to interview the victims of the US invasion of Panama on 20 December 1989.

One Dollar, el precio de la vida [One Dollar, The Price of Life] - Héctor Herrera (2002)

This documentary, one of the starkest in Panamanian cinema, is based on the idea that much of the violence that plagued the working-class neighbourhoods of the capital was the result of the weapons left behind by the US army on 20 December 1989. A responsibility they have never admitted, let alone apologised for.

Los puños de una nación [The Fists of a Nation] - Pituka Ortega (2006)

Based on the life and sporting career of Panamanian boxer Roberto ‘Mano de Piedra’ Durán, Pituka Ortega Heilbron draws a parallel with the negotiations that Panama undertook with the United States to achieve the signing of the Torrijos-Carter Treaties and the recovery of sovereignty over the Panama Canal. But, above all, the idea that the fight against the empire is possible.

Invasión [Invasion] - Abner Benaim (2014)

In Panama, it is often said that we are a country without memory. Based on this idea, the director proposes to the inhabitants of El Chorrillo - one of the neighbourhoods most affected by the US invasion - a re-enactment of what they experienced during that period. This provokes a collective catharsis in those involved that demonstrates that Panamanian society has not recovered (and perhaps never will) from the invasion.

.jpg)

Still taken from La estación seca [The Dry Season] (Jose Canto, 2019)

La estación seca [The Dry Season] - José Ángel Canto (2018)

The best and most honest fiction film in Panamanian cinema. The key to this film is that it refuses to tell Panama's history in capital letters. Instead, it dares to do so through the lives of three losers and a script that borders on the autobiographical, as the cast play themselves and dramatise their lives. Niko wants to study agronomy, but keeps making excuses. Maya is a pregnant surfing champion. Fede can't get a job because of the stigma of having studied film in Cuba. In the existential emptiness experienced by these three characters are concentrated the frustrations of many generations of Panamanians who see how their future is subordinated to the motto “Pro mundi beneficio” and the condition of being a country of passage. These young people are accompanied by the wise voices of Édgar Soberón Torchia and Iguandili López, whose ideas seek to shake us out of our state of stupidity. The former, by pointing out that the very limited idea of education and culture imposed by the creole elite that negotiated the transition to democracy with the United States after the Invasion has kept us from being a better country. The second reminds us that Panama has never had control over its destiny, not even when it succeeded in signing the Torrijos-Carter Treaties. Rather, it has become since then a prostitute at the service of international interests and, above all, of the US empire.

-699x367.jpg)

Still from Panquiaco (Ana Elena Tejera, 2020)

Panquiaco - Ana Elena Tejera (2020)

Cebaldo León, an indigenous Guna who emigrated to Portugal many years ago, suffers from homesickness and decides to return to his comarca in Panama where he hopes to undergo a ritual that will cure his illness. If Abner Benaim's Invasión is based on the idea that Panamanian society suffers from amnesia of traumatic events of the past, Ana Elena Tejera's documentary brings a further nuance to this idea: our memory is plagued by nostalgia and can only be cured by a re-encounter with nature and our cultural roots.

There are other outstanding Panamanian films that distance themselves from the Panama Canal, but in which social inequality is very much present. I am referring to the documentaries Curundú by Ana Endara Mislov (2007), Rompiendo la ola [Breaking the Wave] by Annie Canavaggio (2014) and Los nietos del jazz [The Grandsons of Jazz] by Lucho Araujo (2018).

From this list, an outline could be constructed where Panamanian films are studied in terms of the following themes:

- Visits from Empire

- Memory and oblivion

- The search for our identity

- Social inequality

- The indigenous

- The Afro

In addition to Panquiaco, within Panamanian indigenous cinema there are outstanding works such as the fiction film, Burwa dii ebo by the Ygar Yala collective and the documentary, Bila Burba by Duiren Wagua. Dadjira De [Our House], by the talented Emberá director Iván Jaripio, will be released soon.

In contrast, I must point out that there are few Afro-Panamanian feature films that I could highlight, which is at least curious considering that, according to the latest census, 32.5% of Panamanians consider themselves to be of African descent. However, I hope that this deficit is about to be redressed, as films such as Cuscús [Couscous] by Risset Yangüez, La tierra dividida [Divided Land] by José Ángel Canto, Baba by Harry Oglivie and Pacora by yours truly are currently being developed and produced. All of these projects are marked by our blackness.

There is a sixth category, the most elusive, but perhaps the most poetic of all those I propose in this scheme. This consists of studying Panamanian cinema as a geological entity, based on films such as La felicidad del sonido [The Joy of Sound] by Ana Endara Mislov (2016), and Tierra adentro [Inland] and Luminoso espacio salvaje [Wild Gleaming Space] by the Italian filmmaker and Panamanian nationalised citizen Mauro Colombo (2019 and 2024). These three films tell the story of Panama through the natural phenomena and the singularities of its territory as an isthmus.

-699x393.jpg)

Still from Tierra adentro [Inland] (Mauro Colombo, 2024)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Luis Lorenzo-Trujillo (Venezuela, 1991) is a Venezuelan director and screenwriter based in Panama. He is currently developing his first feature film “Pacora”, a fiction about marronage and the founding of the first black freedmen's settlement in Panama, a project supported in the development category by the Panamanian film fund. He is the screenwriter of La tierra dividida, a free adaptation of the classic Panamanian novel Gamboa Road Gang, about segregation in the Canal Zone. He directed Los retratos, a short documentary that has won awards at the Acampadoc, BannabáFest, Festival Hayah and Festival de Cine Venezolano festivals. He also directed the fiction short El zángano, which premiered at the Panama Horror Film Fest 2022. He is the academic coordinator of the Creative Production Workshop for Central American and Caribbean Film Projects. As a journalist and film critic, in 2016 he founded Material Extra, the first website specialising in Panamanian cinema. His texts on Panamanian cinema have been published in the book Cine Centroamericano y Caribeño Siglo XXI by Extravertida Editorial (Spain) and the magazine Formato 16 by Grupo Experimental de Cine Universitario (Panama). He is a graduate of the master's degree in hybrid cinema from the EICTV (Cuba) and the master's degree in screenwriting from the Escuela Altos de Chavón (Dominican Republic).