Floating visions - Cecilia Sosa

Floating Visions of Puerto Rican vulnerability. Or, how I've become entangled with the '(De)Colonial Ecologies' Project - Cecilia Sosa

Cecilia reflects on her first month working on the project in this blog post.

13 November 2024

As an Argentine sociologist and cultural journalist with a PhD in Drama from Queen Mary (University of London), I started working on ‘(De)colonial Ecologies in 21st-century insular Hispanic Caribbean film’ with lots of enthusiasm but barely any specific knowledge of the Caribbean context. Nonetheless, I was convinced that my training in memory studies and visual arts, and my transdisciplinary research experience in cinema and media cultures, operating at the crossroads of the performance of memory, gender and activism could feed nicely into the project’s main research endeavours and help me to navigate the new environment as smoothly as possible. I trusted that my experience working with survivors of military regimes in Latin America and in community engagement (from cultural organisations to refugees’ forums), as well as my co-creative work alongside filmmakers, activists, and community groups would also help to make a difference in the project. I was particularly thrilled to learn that our activities would centre around an experience of participatory filmmaking alongside Casa Pueblo, a community-based organisation in Adjuntas, Puerto Rico, with a distinctive profile working towards sustainability and energy sovereignty, especially in the wake of the crisis exposed and accelerated by Hurricane Maria in 2017.

Yet, I never thought that “the Caribbean” could generate such a strong impact on my personal view of the contemporary world. After a month or so of being immersed in the Puerto Rican context, reading its theorists and watching its film productions, I felt that there was something overwhelming, sometimes asphyxiating about the struggles currently faced by the country, our main focus during this stage of the project. Puerto Rico, the archipelago traded and transferred from Spain to the United States through the Treaty of Paris in 1898, and since then, successively exposed to debt, forced migration, compulsive sterilisation, toxic military and industrial experimentation, and dreadful climate disasters. The archipelago, in which Puerto Rico is just the most visible island, seemed to literally embody the colonial and environmental decay. This combination, which seemed to be engraved in its environment, emerged as very hard to digest, let alone to dismantle. .

Eventually, I’ve also come to see what Malcom Ferdinand conceptualises as “the double fracture” (2021), with new eyes. For Ferdinand there is a fracture that “separates the colonial history of the world from its environmental history”, which can also be seen “in the divide between environmental and ecological movements, on the one hand, and postcolonial and antiracist movements on the other” (2021: 30). In his ecological thinking, the ontological divide between human and non-human nature is exacerbated by the capitalist devastation of the Earth’s ecosystems and the colonial fracture implanted by Western imperialism. As Ferdinand also argues, “many communities have already proposed alternative relationships” between the human and non-human in our contemporary world (Chaillou, Roblin and Ferdinand, 2020). Thus, the urgency of thinking together both the colonial and environmental devastations became most evident to me by looking at Puerto Rican contemporary independent cinema production. And this is exactly the adventure we are currently embarked on.

Transnational cantos

Since my doctoral thesis – which both queried and queered the traditional bloodline human rights movement in Argentina –, I have further developed a transdisciplinary methodology to explore the imbrications of memory, gender, and performance in the Latin American region. By engaging with actors and cultural materials that did not fall into traditional narratives of the past, I have been able to discover how secret forms of black humour emerged among the victims of violence as a survival mechanism to cope with parental loss, and how former sites of torture could propitiate unforeseen inter-generational encounters. During all these years, I relied on cinema as a methodological and conceptual tool to approach and maybe even produce different realities. For instance, through the analysis of La mujer sin cabeza (The Headless Woman, 2009), one of the less explored pieces directed by Lucrecia Martel, a key auteur of the New Argentine Cinema, I proposed an immersion within the feelings of complicity and denial unleashed by Argentina’s dictatorship, which could also apply to other forms of state violence. I also proposed an unusual reading of La hijas del fuego (The Daughters of Fire, 2018), a lesbian porn film directed by Albertina Carri, a daughter of victims of state terrorism, showing how the film could be grasped as the counterpart of the festive, even ferocious, and unprecedented feminist awakening. Cinema also emerged as an affective point of entrance for a comparison between Colombian and Argentinean imaginaries of violence through a series of screening sessions and focus groups we conducted within different communities in both countries.

Indeed, among the transnational projects I have been involved in there is one that feels particularly aligned with “Decolonial Ecologies”. “Screening Violence: A Transnational Study of Post-Conflict Imaginaries” (2018-2021), also based at Newcastle University, allowed me to work with film reception as well as boost my skills as a film producer and curator. I joined a team of filmmakers and academics to conduct mixed participatory approaches to peace-building in Indonesia, Northern Ireland, Colombia, Algeria, and Argentina. While developing an innovative cinematic approach to different environments, together with my colleague Philippa Page, we designed and coordinated over 20 film reception studies and screening sessions, focus groups and in-depth interviews during extended ethnographic sessions in Argentina. This qualitative data informed Cantos Insumisos (Rebel Songs, Alejo Moguillanksy, 2023), an experimental documentary that we co-produced and co-curated together that addressed the cross-fertilisation of gender and imaginaries of violence in post-dictatorship Argentina. The film managed to put together the kaleidoscopic cacophony of voices, images, gestures, stories, and silences that composed the “magma of social imaginary significations” (Castoriadis, 1987: 344) of the country’s 1976-83 military dictatorship. Cantos insumisos shows how the haunting memory of those “disappeared” during the authoritarian past overlaid and was nurtured by a more recent feminist activist wave that contested long-standing forms of patriarchy. The palimpsestic layers of imaginaries transposed onto celluloid complicate the already diffuse boundaries between past and present in the country. When editing the film, Alejo, our filmmaker, reflected that the process was going to resemble rewriting a long poem divided into cantos, like those of the Divine Comedy. Facing the new Caribbean scenario, a similar state of anxiety started to formulate a new set of questions: what kind of new cantos [songs] were waiting for us within the Puerto Rican context? How would we navigate the new Dantesque labyrinth of Puerto Rico’s past and present? Which new local stories might we be able to awake, activate, and treasure upon arriving at Casa Pueblo, our partner organisation in Adjuntas?

Cinema as a method

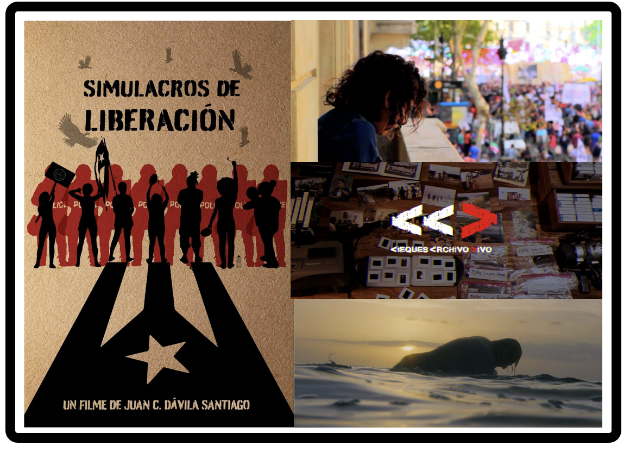

Montage 1: From left to right

Simulacros de Liberación (Drills of Liberation, Juan Carlos Dávila, 2021)

Cantos Insumisos (Rebel Songs, Alejo Moguillanksy, 2023)

Vieques: un archivo vivo (Vieques, a living archive, Juan Carlos Rodríguez, 2023)

El silencio del viento (The Silence of the Wind, Álvaro Aponte-Centeno, 2023)

In the last month, I’ve immersed myself in accounts of Puerto Rican environmental and social justice activism to further explore how the region has been responding to ecological challenges while addressing its colonial heritage and condition. In fact, this immersion in the Puerto Rican landscape has so far occurred mainly through cinema. Thus, the films, both documentaries and fiction, came as a “block of sensations”, as Brian Massumi describes the affective power of cinema in Parables for the Virtual (2002). The spectrum of local cinematic production brought sounds, narratives, tensions, and colours, which worked as an affective terrain of passage for my brand-new exploration of the Caribbean region. For Giuliana Bruno, a landscape is, in many ways, “a trace of the memories and imaginations of those who pass through it, even filmically” (2002: 251), immediately connecting film (and also filmmaking) with an ecological memory of the land. “Memory is fundamentally ecological”, argues the memory scholar Astrid Erll within a recent special issue on Memory and the Environment that has recently inaugurated the journal Memory Studies Review (2024: 17). This connection becomes particularly poignant in Puerto Rico. Its local cinema production can also be conceived, in Bruno’s terms, as “a modern cartography”, a haptic form of sightseeing in which images turn into a geography of lived memories, and eventually also a living space (2002: 71). In this sense, cinema became the entrance point for my fieldwork, and in many ways, also the haptic terrain in which my own emotions in relation to that landscape materialised.

In fact, while engaging with the history of the island through its film production, I was amazed to discover the extent to which the nuances of the documentary filmmaking and the environmental justice struggles of a non-autonomous country seem to coincide. Paradoxically, without being an independent state, Puerto Rico has shown a strong connection between cinema and nation-building, as Naida García-Crespo argues in her book Early Puerto Rican Cinema and Nation Building: National Sentiments, Transnational Realities (2019). Drawing upon this contested but thought-provoking insight, I wonder if Puerto Rican cinema could emerge as an appealing point of entrance to approach the “double fracture”, as addressed by Ferdinand for the Caribbean region. The notion of Puerto Rican cinema as a (frustrated) national project might harbour an expanded opportunity to think of cinema as the point of encounter of “multidirectional memories,” to use Michel Rothberg’s expression (2009). There, the palimpsestic layers coming from the Spanish colonial and slave-trading past crosspollinate and intertwine with decades of US neo-colonial exploitation. Perhaps, and by the same token, cinema might also enable us to envision glimpses of a decolonial project for the country’s human and non-human inhabitants. During this month, I have treasured a few haptic memories that might lead us in that direction.

My initial overwhelming feeling could also be described as a block of sensations irrupting from my film-meditated approach to the territory. The affective waves and shapes of the cinematic imaginaries brought for me contorted, agonistic images of clashing ruminations on “Caribbean paradise”, toxic debris, unrelenting youth emigration, massive debt and exploitation, among other impacts of disastrous development, or desastrollo, on human and non-human nature. Still, and at the same time, the independent production also left space for hope. For instance, in Alexander Wolfe’s documentary Semitostado (Semi-toasted, 2012), the history of colonial dependency and its disastrous consequences both human and non-human, gets entangled with glimpses of autogestion emerging from grassroots community movements.

The power of an emergent decolonial project-to-come runs throughout Juan Carlos Dávila’s documentary oeuvre, becoming clearer and more explicit with each work. As he shows, different visual imaginaries clash in Puerto Rico; on one hand, we have the tenebrous image of “Muerto Rico” [Dead Rico], “a not-so-playful play on words” that was used during the protests of the summer of 2019, and that finally accounts more broadly for the “afterlife of colonisation and enslavement” in the archipelago (Lebrón Ortiz 2021). On the other hand, we see the “Marcha de la luz” (March of Light), the procession organised by Casa Pueblo in the same year, advocating for sustainable and community-based solar power to respond to the energy chaos revealed by Hurricane Maria. In his latest feature-length film, Simulacros de Liberación (Drills of Liberation, 2021), Dávila portrays himself within what starts as a project to document the effects of austerity on the island pre-Maria, and later becomes the live portrait of Governor Ricardo Rosselló’s decay and resignation in July 2019 after days of mass street protests. In one of the sequences, Dávila follows a student demonstration against the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act, the so-called PROMESA, enacted by the United States Congress in 2016 to address Puerto Rico’s fiscal crisis through a big capital-aligned Management Board or Junta that is continually denounced and mocked within the film. For the protest, students have painted Puerto Rico’s flag in black. “Why the black flags?”, inquires the filmmaker. “Puerto Rico’s flag will be black, until the real colours can be revealed”, argues the activist. New colours to be revealed. I was amazed at how this single, almost childish image could also reveal an appealing vision of a decolonial future to-come, a future that contemporary Puerto Rican cinema might contribute to unveiling; a process that our project would be willing to embrace.

Vieques: un archivo vivo (Vieques: A Living Archive, 2023), a documentary film developed by scholar and filmmaker Juan Carlos Rodríguez, addresses the poignant story of Vieques over 25 years. Through intimate recollections, community voices, and archival footage, the film exposes the profound hardships endured by the island that was occupied by the US Navy in 1941 and used as a training ground and bombing practice site until 2003. It also portrays the personal journey of the filmmaker returning to the island twenty years later, now with a wife and 7-year-old son. The sense of “unfinished business” conveyed by the documentary coexists with the sense of how archives expand their existence beyond individuals to be recalled, and potentially reactivated, for unexpected community projects. Particularly compelling is the way in which the film engages with decades of women’s activism. This feminist presence in Rodríguez’s piece also suggests one of the protagonists in the struggle against environmental degradation and for an alternative future in the island. Moreover, it sheds light on how an ontological turn in feminism can also be understood as an eco-ethical push towards a new way of conceiving non-human vulnerability. In this sense, Deniz Gündoğan İbrişim argues for a feminist approach to the environment through her concept of “response-able memory”, which proposes a non-anthropogenic form of remembrance as a strategy for the field in the twenty-first century (2024).

At the same time, fiction films also offer a touching affective imaginary of how the colonial past and present are connected and speak to each other within the current context of environmental decay and human exploitation. For instance, in El silencio del viento (The Silence of the Wind, 2023), Puerto Rican director Álvaro Aponte-Centeno allows us to grasp some of the contradictory entanglements of human and environmental fractures coinciding in the island. The film depicts how a family makes a living trafficking illegal immigrants from Santo Domingo. As the final link in the chain of a larger smuggling network that brings mainly Haitian asylum seekers from the Dominican Republic, they are also victims of the system of degradation they perpetuate. The threads of contorted mediations of exploitation have no end. The last scene of the film is particularly poignant. The engine of the fragile boat carrying a new batch of immigrants has broken down, leaving it floating defenceless in the sea. That final image emerges as the reverse of Ferdinand’s vision of a “World-Ship”, a ship that reaches and survives “the eye of the tempest”, tracing the path towards a world free of slavery, social violence, as well as political and environmental injustice, what he ultimately calls “a decolonial ecology” (Ferdinand 2021: 3).

Nonetheless, when the storm comes in Aponte-Centeno’s film, the boat eventually sinks, with equal results for all its passengers. Spectators follow the distressing fight of the protagonist against what becomes inevitable. In contrast to Ferdinand’s vision of the “World-Ship”, no possibility of reparation is contemplated in the film. Still, the ubiquitous presence of nature, beautifully portrayed throughout the film, seems to suggest how much lives are inevitably exposed to human and non-human forces beyond their control. The sound of a last sequence, shot underwater, is terrifying, almost unbearable. A cry of resistance comes from below and it is not necessarily (or not exclusively) human. The whole landscape seems to be crying out, until a last, abrupt cut when everything becomes suddenly silent. The cut seems to transfer an ethical responsibility to spectators: the urgency of listening to a cry revealing a common vulnerability between human life and the environment— that shall not remain silent.

A floating “joke”

Montage 2: From left to right

Comedian Tony Hinchcliffe at Madison Square, New York, on Sunday 27th of October 2024. Source: BBC News

Plastic waste and other debris from the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Source: Greenpeace

However, another vision came to interrupt my affective immersion in the contemporary Puerto Rican cinematic landscape. While following the updates of the latest US elections, maybe the closest and most dramatic within the country’s history, I was shocked to learn about the alleged “joke” in which the comedian Tony Hinchcliffe addressed Puerto Rico as a “floating island of garbage in the middle of the ocean”. Like many around the world, I felt ashamed of such an extreme expression of racism, exposed from the public stage at Madison Square Garden during the final weeks of Trump’s campaign.

Just a few weeks before, I had heard from one of our local partners in Casa Pueblo that the results of the election would not alter their plans on the island. The binary dispute taking place on the mainland appeared not to be decisive. Such a perspective is perhaps unsurprising when we consider that not only do Puerto Ricans resident on the archipelago not have the right to vote in federal elections, but the current crisis is the result of a series of failures, withdrawals, and necropolitical decisions by Republican and Democratic leaders alike (Cabán 2021: 23). However, when “the floating garbage” image went viral, prompting fierce responses from the Puerto Rican diaspora, including popular artists, the need to recover the Latino vote became the recurring message for the final push of the Republican campaign. After all, Puerto Ricans resident in the mainland US can vote in federal elections, and in fact, nearly two thirds of Puerto Ricans (about 5.8 million) currently live in the United States, many within the swing states whose response could define an already tight dispute. Hinchcliffe’s racist insult –seemingly uttered as a joke – had placed the question of the “Latino vote” centre stage.

Yet, beyond electoral speculations, the “joke” continued resonating alongside a visual imaginary difficult to convey. To some extent, the image of garbage floating in the ocean recalled the Pacific Gyre’s debris, which, as denounced by environmental organisations, “is roughly the size of Texas, containing approximately 3.5 million tons of plastic, including shoes, toys, bags, pacifiers, wrappers, toothbrushes, and bottles too numerous to count”. As Stacey Alaimo analysed, the cloud of eternal debris emerging as the “banal but persistent detritus of consumerism” (2016: 130), is also a reminder of how “the plastic anthropocene, manufactured by humans but beyond human control, not only surrounds us but invades us, literally trans-forming our flesh” (2016: 188). At the same time, the floating-garbage joke also appeared as the inverted, dystopian version of Ferdinand’s vision of a “World-Ship”, seeking to provide reparation for the combined history of abuse and degradation of both human and non-human nature. Thus, in many overlapping ways, Hinchcliffe’s joke proposed an exponential reiteration of extreme racial and colonial violence in a period of political and ecological anxiety.

Moreover, in a Freudian sense, the joke also seemed to reflect the unwanted emergence of the colonial unconscious. At some point, it occurred to me that the "joke" might reveal a sort of colonial "aphasia": the US’ refusal to deal with the consequences of its own colonial practices, both in terms of non-human and human ecological excesses. Ann Marie Stoler uses the term "aphasia" to describe how colonial societies selectively “forget” or suppress uncomfortable knowledge, histories, or memories, particularly those that challenge dominant power structures or reveal past violence and exploitation. For her, colonial aphasia is both “a political disorder and a troubled psychic space” (Stoler 2011: 153) affecting empirical formations. Inadvertently, a similar operation seemed to be at stake during Trump’s rally at Madison Square. The joke uttered by his commissioned entertainer somehow broke the pact of silence. It made present something that had been selectively hidden: the sense of responsibility (and maybe also guilt?) that the mainland bears for the fate of its own colony alongside its disavowal to recognize their demands for justice. The joke of naming Puerto Rico as a “floating island of garbage” touched a double-blind spot: US’ practices of oppression and dispossession towards its own colony, and it also made present an ecological anxiety, barely recognised during Trump’s campaign. In that manner, the joke became expressive of an agonistic memory hidden behind an exacerbated imperial power.

The next stage of the “(De)colonial Ecologies” project will involve a participatory filmmaking workshop alongside the community of Adjuntas, which will take place in December 2024 in partnership with Casa Pueblo. The workshop will be the first phase of a participatory film that we are hoping to produce together with local participants. The project will continue in February 2025 with the actual filming of the participatory piece and a “Junte” that will gather local filmmakers and community organisations to discuss the perspectives of community filmmaking as a form of decolonial practice. One of the sessions planned for December will be dedicated to the collective design of storyboards. Participants will be encouraged to sketch, and eventually frame, the stories they would like to tell about Adjuntas’ past and present. The storyboards will convey both documentary and fictional stories. As researchers, we will try to facilitate this activity while providing a safe, communal path for the stories to emerge. Hopefully, the emerging imaginary sheds light on novel, experimental connections between environmental crisis and colonial degradation. Against alleged electoral jokes, this research adventure might contribute to mobilising other community-based narratives, new ecologies of shared vulnerability that could offer some visual and affective response to the violence uttered by aphasiac comedians while bringing some glimpses of novel collective pleasure.

References

Alaimo, Stacy. Exposed: Environmental Politics and Pleasures in Posthuman Times, University of Minnesota Press, 2016.

Bruno, Giuliana. Atlas of Emotion: Journeys in Art, Architecture, and Film, Verso, New York, 2018.

Cabán, Pedro. ‘1. Puerto Rico: The Ascent and Decline of an American Colony’. In Critical Dialogues in Latinx Studies: A Reader, edited by Ana Y. Ramos-Zayas and Mérida M. Rúa, 13–26. New York University Press, 2021.

Chaillou, A., Roblin, L; Ferdinand, M. Why We Need a Decolonial Ecology?, Green European Journal, 2020. https://www.greeneuropeanjournal.eu/why-we-need-a-decolonial-ecology/

Erll, Astrid. Transculturality and the Eco-Logic of Memory. Memory Studies Review, 1(1), 17-35., 2024. https://doi.org/10.1163/29498902-20240002

Ferdinand, Malcom. Decolonial Ecology: Thinking from the Caribbean World. John Wiley & Sons, 2021.

Gündoğan İbrişim, Deniz. “Feminist Posthumanism, Environment and ‘Response-Able Memory’”. Memory Studies Review, 1 (1), 93-111, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1163/29498902-20240004

García-Crespo, Naida. Early Puerto Rican Cinema and Nation Building: National Sentiments, Transnational Realities, 1897-1940. Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press, 2019.

Lebrón Ortiz, Pedro. “Death and Temporality in Against Muerto Rico”, Caliban’s Readings, 31 December 2021. https://caribbeanphilosophy.org/blog/death-temporality

Rothberg, Michael. Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization, Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2009.

Stoler, Ann Laura. “Colonial Aphasia: Race and Disabled Histories in France”, Public Culture 23 (1): 121–156, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-2010-018