Building the Machine - Emily A. Maguire

Building the Machine: Reflecting on Tropical Time Machines: Science Fiction - Emily A. Maguire

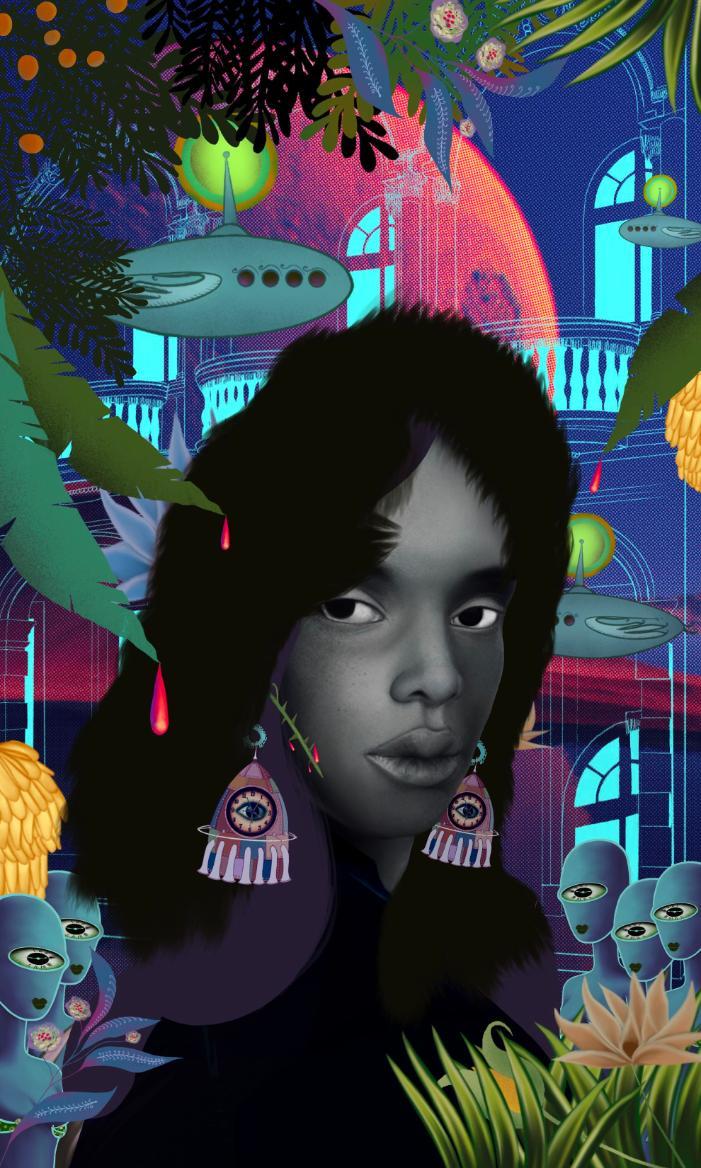

We are delighted to present our first guest blog post, in which Professor Emily A. Maguire (Northwestern University) talks about the story behind her new book. Tropical Time Machines is of particular relevance to the '(De)colonial Ecologies' project because of its engagement with the reflections on temporality evident in recent insular Hispanic Caribbean culture - especially film. As we will see below, the book considers how science fiction is harnessed to critique colonial imaginaries of the region and envision alternative futures. What's more, the genre engages with ecologies (relationships among humans and between humans and non-human nature) in critical, apocalyptic, and speculative ways.

6 December 2024

If you had told me, as I was completing my graduate work, or even during my first year as an Assistant Professor, that I would go on to write a book about science fiction, I would have been extremely surprised. There was nothing in my brief flirtation with science fiction as a reader of it in high school at early college – nor of my experience of as a reader of Latin American literature – to highlight it as a potential area of research interest. Of course, the paths by which we find our way to research projects often involve instances of serendipity or unexpected encounters. Yet in the case of what became my book Tropical Time Machines: Science Fiction in Contemporary Caribbean Literature (University Press of Florida, 2024), the path by which I found my way to science fiction runs curiously parallel to its rise in Caribbean cultural production.

The moment when it began for me (although I did not yet know it) took place in May 2001. I was in Havana, in a peso bookstore in la Habana Vieja, when my friend Alexander Pérez Heredia, then a researcher at the Instituto de Literatura y Lingüística, thrust a paperback volume into my hands, saying, “Este libro es muy bueno.” The “really good book” turned out to be the first edition of Raúl Aguiar’s La estrella bocarriba, which had been published that year. Although not strictly science fiction, my fascination with Aguiar’s novel about a group of “friquis” and their creation of an alternate reality through drugs, heavy metal music, witchcraft, and a renaming of their world, led me to investigate Aguiar’s work. This led to my discovery of Yoss’s Reino Eterno (1999), an anthology of recent science fiction and fantasy writing, which opened my eyes to the science fiction being written in Cuba. When I went to Cuba in the summer of 2008, I asked a colleague to help put me in touch with both Yoss and Aguiar. They turned out to be not only incredibly generous interview subjects (who eventually became friends); they introduced me to the world of Espacio Abierto, the ongoing science fiction writing workshop run through the auspices of the Centro Onelio Jorge Cardoso in Miramar.

In retrospect, two things about this 2001 moment stand out: first, of the novels, short stories, videos, films, and visual art that I analyze in my study, only two of them – Michel Encinosa Fu’s Niños de neón (2001) and Rafael Acevedo’s Exquisito cadaver (2001) – had been produced by the time I picked up Aguiar’s novel. Since I first began working on science fiction in earnest, around 2007, the publication of science fiction novels and short stories – both in print and online – has exploded, alongside the increasingly frequent appearance of science fiction in films, music videos, theatre, and visual and digital art. My research has been an attempt to understand this remarkable rise in the presence of science fiction in the cultural production of the Spanish-speaking Caribbean and its diasporas over the last two decades, as it has been happening – an exhilarating ride that has sometimes had me struggling to keep up with the proliferation of new science fiction texts (and revising the book’s structure as I did so).

In contrast to other parts of Spanish-speaking world, Caribbean interest in science fiction is relatively new; with the exception of a few precursors, Cuban writers didn’t begin to publish in the genre until the 1960s, and it has only gained a recognizable presence in Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic in the last two decades. Furthermore, science fiction’s presence in literature, film, and video is now no longer confined to closed communities of “genre” creators and fans. As the distribution of different media has diversified, science fiction has moved beyond the popular constraints of “genre fiction” and the audiences inscribed by these communities of fans to position itself within the cultural mainstream. As I have followed the rise of science fiction elements in Caribbean literature and film, my central questions, throughout these nearly two decades, have been: Why are Caribbean creators gravitating to science fiction as a mode of storytelling? and What does the genre reveal about the region’s experience of our current moment? My attempt to answer these questions began in Cuba, where a dedicated community of science fiction writers and fans was already well established, but has followed the appearance of science fiction texts, creators, and communities of fans to Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic and beyond.

To explain the significance of science fiction’s appearance in recent Caribbean cultural production, I first needed to consider what constitutes science fiction and how the genre operates in a Caribbean context. This involved a (still ongoing) (re)training in science fiction, since, as Paul Kincaid has noted, the genre is notable for how much has been written attempting to theorize its existence (13). I found that many definitions could not fully account for the recent Caribbean cultural production I encountered, in which science fictional elements sometimes existed alongside or in addition to other narrative modes, such as the fantastic, in the same text. In my approach to these hybrid texts, I have been guided by writer and critic Samuel Delany’s vision of science fiction as a mode of expression. According to Delany, if realism can be said to describe “what has happened” or “what could have happened” and fantasy describes “what could not happen,” science fiction’s difference operates through the way in which it describes – with verisimilitude – a “events that have not [yet] happened” (11). Seen this way, science fiction might be said to be a language that seeks to describe an experience in the subjunctive plane of the future possible, rather than the dreamed or the imagined. At the same time, in their deployment of science fiction, Puerto Rican, Cuban, and Dominican writers and artists are redrawing the genre’s outlines, pushing readers and viewers to expand their understanding of what constitutes the “future,” and counts as science, as well as what can be imagined as possible.

The second thing I note about that moment of discovery in La Habana Vieja is that 2001 marked the last time Alex and I would be together on Cuban soil. He would leave Cuba in 2003, following the failure of Oswaldo Payá’s Proyecto Varela and the Cuban government’s subsequent crackdown. If the two decades of cultural production that form my study’s corpus have been marked by increasing communication and collaboration between writers, directors, artists, critics, and fans, they have also been marked by various kinds of upheaval, and these emerging networks of Caribbean creativity have increasingly included those in diaspora. The visions of alternate worlds I examine have been produced against the backdrop of hurricanes and apagones [power cuts], food shortages and street protests, government crackdowns and a global pandemic. If science fiction texts fall under what Darieck Scott, in his study of super-hero comics, terms “fantasy-acts” (35), the cultural artifacts I analyze offer themselves as “counterpropositions” to this reality. While still making visible the weight of the past and the heaviness of the present, these works of imagination are meaningful precisely because they constitute “not waiting” (36), as Scott puts it; they intentionally open space for visions of what Yomaira Figueroa-Vásquez terms “worlds/otherwise.”

Tropical Time Machines argues that science fiction in the Hispanic Caribbean is significant for the ways in which the genre engages with temporality. If other genres and previous iterations of Caribbean cultural production have positioned the region as exceptional, outside of Western temporal structures, occupying a repeating or static time, even anchored to the past, science fiction as a mode of narration breaks this cycle, establishing a different relationship not only to the future but to global understandings of history, temporality, and interconnectedness. In the four subsets of texts I examine – the ab-real (irrealist texts that reveal reality’s own fabricated nature), cyberpunk, zombie fictions, and post-apocalyptic narratives, science fiction’s future possible intervenes to highlight temporal stagnation, to make visible outmoded systems that continue to operate in the present, to offer alternative visions of Caribbean reality (both utopian and dystopian), and to argue for radically new ways of envisioning both socio-political futures and the literary canons on which national identities and histories are built. Despite the dark tone of some of the works I analyze, I see science fiction in Caribbean cultural production as active imagining working to expand and make visible the “horizon of possibility.” These texts themselves function as time machines, projecting future Caribbean imaginings in which time and place are intimately connected. These fictions attempt to break the reader out of their own stuck ideas of Caribbean time and space, just as they’ve helped me to shift and reframe mine.

Emily A. Maguire, Northwestern University

Works cited

Acevedo, Rafael. Exquisito cadáver. Ediciones Callejón, 2001.

Aguiar, Raúl. La estrella bocarriba. Letras Cubanas, 2001.

Broderick, Damien. Reading by Starlight: Postmodern Science Fiction. Routledge, 1994.

Delany, Samuel L. “About 5,760 Words.” The Jewel-Hinged Jaw: Notes on the Language of Science Fiction. 1978. Introduction by Michael Cheney, Wesleyan UP, 2009, pp. 1-15.

Encinosa Fu, Michel. Niños de neón. Letras Cubanas, 2001.

Figueroa-Vásquez, Yomaira C. Decolonizing Diasporas: Radical Mappings of Afro-Atlantic Literature. Northwestern UP, 2020.

Kincaid, Paul. What It Is We Do When We Read Science Fiction. Beccon Publications, 2008.

Scott, Darieck. Keeping It Unreal: Black Queer Fantasy and Superhero Comics. NYU Press, 2022.

Yoss, ed. Reino eterno. Letras cubanas, 1999.